Japan has one of the world’s highest literacy rates. Japanese people spend over 4 hours per week reading. And students in Japan score extremely highly on international literacy benchmarks tests. Unusually, for these tests Japanese boys score slightly higher than girls when reading skills are measured in this manner. Photograph: Arnaud Titoy CC. 2.0.

Japan has one of the world’s highest literacy rates. Japanese people spend over 4 hours per week reading. And students in Japan score extremely highly on international literacy benchmarks tests. Unusually, for these tests Japanese boys score slightly higher than girls when reading skills are measured in this manner. Photograph: Arnaud Titoy CC. 2.0.Even though Japanese authors and publishers have been massively influenced by international trends and books translated into Japanese, they have focused quite understandably on their own large local market, and have expressed themselves in Japanese for local consumption.

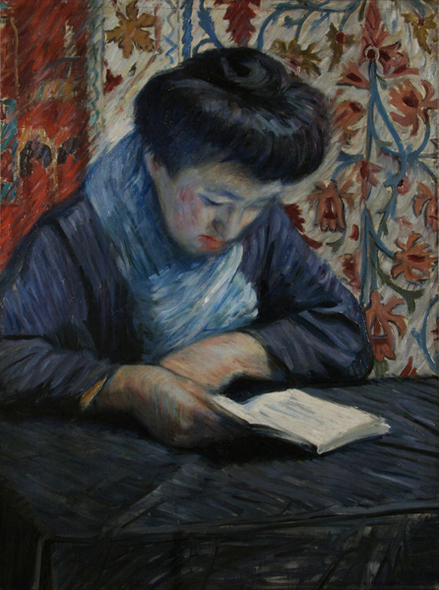

Reading, by Tsune Nakamura (1887-1924). Nakamura was born in Mito, Ibaraki Prefecture North of Tokyo, into a samurai family. He become an artist (Yoga school) after contracting tuberculosis, which forced him to abandon a military career. Photograph: Public Domain.

Reading, by Tsune Nakamura (1887-1924). Nakamura was born in Mito, Ibaraki Prefecture North of Tokyo, into a samurai family. He become an artist (Yoga school) after contracting tuberculosis, which forced him to abandon a military career. Photograph: Public Domain.More titles than ever before are now available in Chinese, Russian, German, English, Italian, French, Thai, Spanish and many other languages. Haruki Murakami whose works have been published in 50 languages, and Banana Yoshimoto who was first published internationally outside Japan in Italian, have opened the eyes of a new generation of international readers to compelling storytelling that Japanese readers have been enjoying quietly for decades.

The latest cohort of Japanese writers breaking through are currently hard to define, but are following in the paths of some brilliantly gifted predecessors. People like the idiosyncratic avant-garde writer Yukio Mishima (1925-1970), a member of what is termed the Second Generation of major Japanese writers that appeared after the Second World War; and Shusaku Endo (1923-1996) whose book Silence was recently adapted for film by Martin Scorsese and released in 2016, starring Andrew Garfield, Liam Neeson and Tadanobu Asano. Many enormously talented writers have subsequently followed, and continue to delight readers as well as influence and encourage up-and-coming writers. One such writer is Kenzaburo Oe who won the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1994.

The so-called Galapagos syndrome, a term first used to describe how parts of Japanese culture and industry have developed in isolation, independently of international trends and globalization, can also be applied to a certain degree to its large community of authors, publishers and readers.

Japanese poetry, for example, developed independently, creating unique short-form writing and poetry such as Tanka and Haiku, centuries before Twitter, the short-form writing of our era, which restricts posts to 140 characters compared to the 17 syllables allowed in traditional Haiku. Haiku is well known internationally for its elegance and grace, which is where the similarities with the vast majority of Twitter’s tweets probably ends. Nevertheless, fans across the globe – adults and children – do interact, connect and create, often with style and intelligence, through international competitions run by the Haiku Society of America, The British Haiku Society, and other such organizations.

The genres of travel, diary, short story and novella writing have also long occupied an important and prestigious place in Japanese literature. The diaries of Court Ladies in the Heian Period (794-1185). Yoko Ogawa’s prize-winning short story Pregnancy Diary included in her collection of three novellas The Diving Pool and published by The New Yorker in its December 26th issue in 2005, is a contemporary example of the diary genre. Many believe that Japan is experiencing a second Golden Age with writers such as Ogawa, Mitsuyo Kakuta, Hitomi Kanehara, Risa Wataya and others.

Another highly creative and interesting period was the Edo Period (1603-1868) when Japan was almost completely closed to Western influence.

Woman Reading, woodblock print, by Utagawa Kuniyoshi, one of Japan’s master printers, born in 1798. Between 1815 and 1817, he created a number of book illustrations for Yomihon, Kokkeibon, Gōkan and Hanashibon helping create a book loving population that still exists today. Image: Public Domain/Wikipedia.

Woman Reading, woodblock print, by Utagawa Kuniyoshi, one of Japan’s master printers, born in 1798. Between 1815 and 1817, he created a number of book illustrations for Yomihon, Kokkeibon, Gōkan and Hanashibon helping create a book loving population that still exists today. Image: Public Domain/Wikipedia.The Meiji Era (1868-1912), when Japan was liberalizing and opening up to Western influence, after hundreds of years of isolation during the Edo Period that preceded it, was another important period for Japanese literature. A very determined Japan was trying to catch up in an intense technology race: economically and culturally. Japan rapidly adopted new technologies, including printing technologies, and Western-style dress, with breathtaking speed. The technological and social changes also impacted on reading habits. New narratives and writing styles, that Japanese readers and creative writers had never been exposed to, were suddenly available in translation.

Literacy rates doubled, reaching 80 percent. Around the World In Eighty Days and Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea, published in Japanese for the first time, for example, were hugely popular, and had a major impact on Japanese authors and readers, as did Sir Thomas More’s Utopia (1516), which was published in Japanese for the first time in 1882. As is so often the case in Japan, the country learnt, absorbed, adapted and then developed its own independent approaches. Old style traditional prose was replaced; literary journals and magazines were launched; short story writing flourished; and new works (translations and local originals) were published often in instalments. This started a popular tradition that is still evident today in brilliant novella writing, and the widespread commissioning and serialization in newspapers of new creative writing.

It took longer for Japan’s community of writers to successfully adopt and develop what they learnt from the new books they read in translation than it took other parts of Japan to learn how to brew beer, distill whiskey and mechanize. It took time, but it has led to an extraordinary creative revival in Japanese literature that many are still unfortunately unaware of. A revival that, according to leading Japanese commentators, European and American writers have paid scant attention to.

Despite this, the reality is that there is a growing interest and awareness of literary genres with rich histories in Japan that are still vibrant and compelling today. These include Ghost Stories (Yokai), Crime Fiction (Suiri Shosetsu) and the traditional short story that many authors including the Nobel Prize-winning author Yasunari Kawabata (1899-1972) have written and encouraged.

Brilliant novella are still being written today and are even morphing into new styles and formats such as the light novel (raito noberu), which generally target high-school students with short attention spans. These books are typically no longer than 50,000 words. Awareness of this uniquely Japanese format is increasing. It has been identified by the Hachette Book Group (HBG) as an important new opportunity; one that it is trying to develop for readers outside Japan through its joint-venture with Yen Books and Kadokawa in the United States.

There are numerous worthy books and academic courses on Japanese literature and literary theory, which have a long, well-documented and researched history. However, it is easy to be put off by some of the intellectualism and the perceived barriers that exist due to the Japanese language and culture. Despite this, contemporary Japanese literature and creative writing are as vibrant, exciting and readable as ever, and fully reflect Japan today and its changing position in the world.

This dynamic and creative landscape is reflected by the fact that Japan has around 500 different literary prizes, and publishes 80,000 new books each year. Some literary prizes target new writers, others specific genres such as the Seiun Award for the best science fiction, awarded by the Federation of Science Fiction Fan Groups of Japan (FSFFGJ). This was first awarded in 1970 to Yasutaka Tsutsui, another master of the short story format and the author of The Girl Who Leapt Through Time, a story about a time traveling girl that was first published in book form in 1967 after serialisation, and released as an animated film in 2006.

Contemporary Japanese literature has the potential to excite and capture readers when they can access the best of Japanese writing in their own languages. Once readers outside Japan discover Japanese authors and literature for the first time, it often generates a long-term appetite for and fascination with the country’s fiction.

© Red Circle Authors Limited

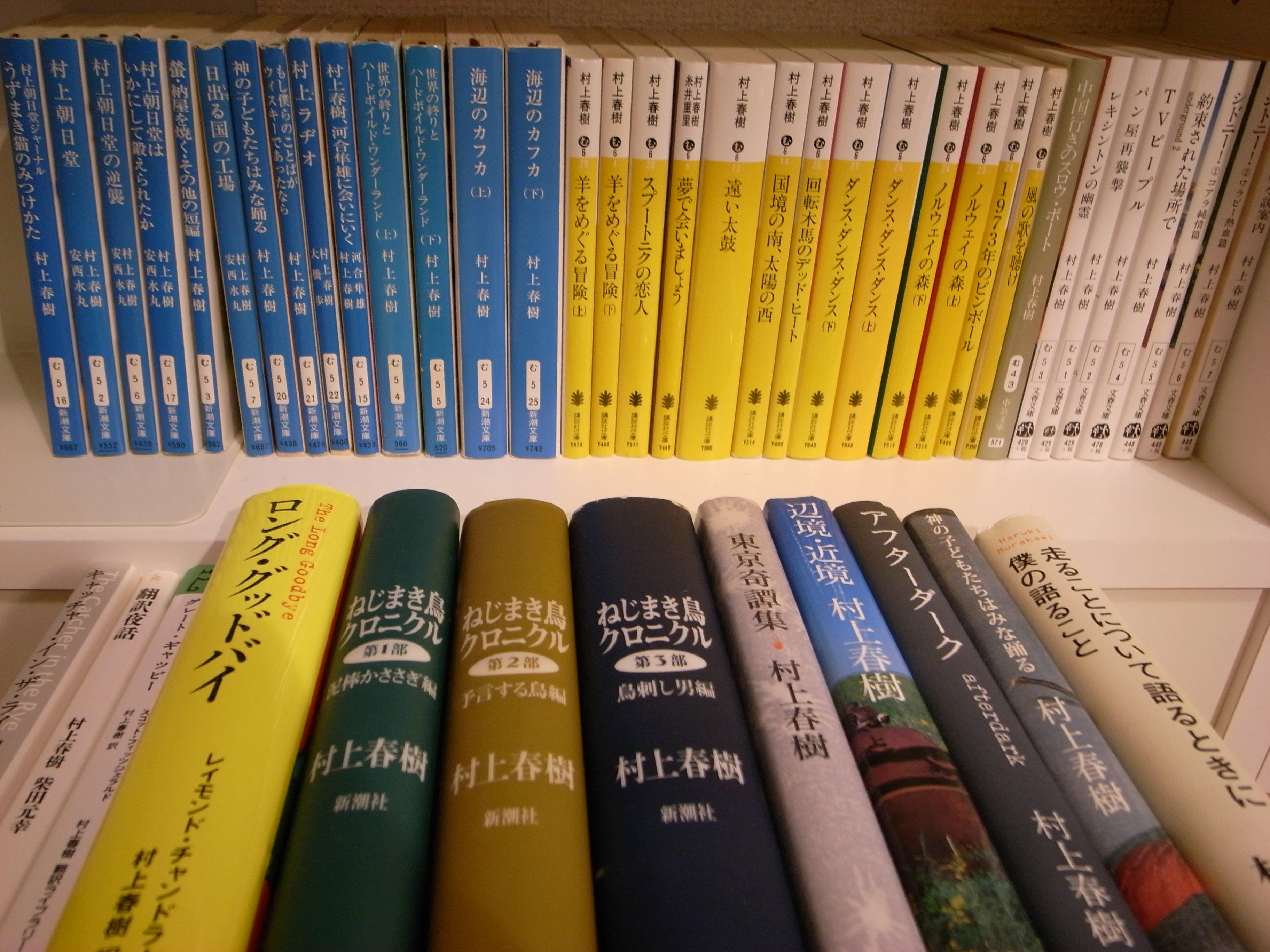

While at university in Tokyo Haruki Murakami met his wife Yoko, worked in a record store and founded a jazz bar and coffee shop called Peter Cat, which they ran together between 1974 and 1981. He published his first novel, Hear the Wind Sing, in 1979. Photograph of some of his many novels by Nappa, CC 2.0.

While at university in Tokyo Haruki Murakami met his wife Yoko, worked in a record store and founded a jazz bar and coffee shop called Peter Cat, which they ran together between 1974 and 1981. He published his first novel, Hear the Wind Sing, in 1979. Photograph of some of his many novels by Nappa, CC 2.0.