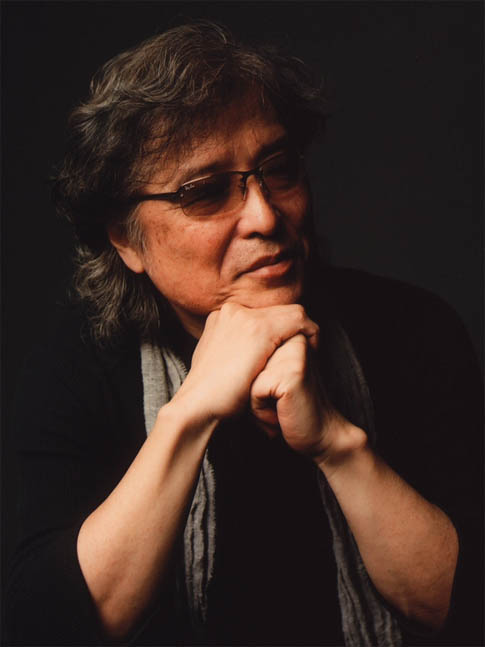

Soji Shimada

“I still love writing whodunnits but today, I write for a much more general audience, and am not only fixated on Japan’s large number of fanatical mystery fans.”Soji Shimada showed a flare for writing crime fiction and detective stories from a very young age, and was already building up a fan base in primary school, where he would read his short stories to his classmates in their lunch breaks. It wasn’t, however, until he was in his mid-twenties that he thought writing might actually be a possible career option. This newly forged ambition led to Shimada writing his first novel, a massive bestseller, when he turned 30, turning Shimada and his detective Kiyoshi Mitarai into household names in Japan.

Since then Shimada has written over a hundred novels and continues to write brilliant whodunnits that baffle readers with unfathomable murder mysteries, ingenious plots and unusual twists. Nowadays he also enjoys penning the occasional satire, as well as writing parodies and on occasion even science fiction.

“In a series of postmodern asides Soji Shimada repeatedly taunts the reader explaining that all the clues are there for an astute observer,” The Guardian.

-

Original, Short and Compelling Reads

Original, Short and Compelling ReadsOne Love Chigusa

by Soji Shimada

A love story that explores the mechanics of the heart and humankind’s inevitable evolution. One Love Chigusa by Soji Shimada, one of Japan’s most famous authors, is a tale of obsessive love in a world where technology has crept into the very heart of humanity.

- Soji Shimada

Soji Shimada born in 1948 in Fukuyama City, Hiroshima is considered locally as one of Japan’s most famous living authors, and earned his moniker as Japan’s God of Mystery a long time ago.

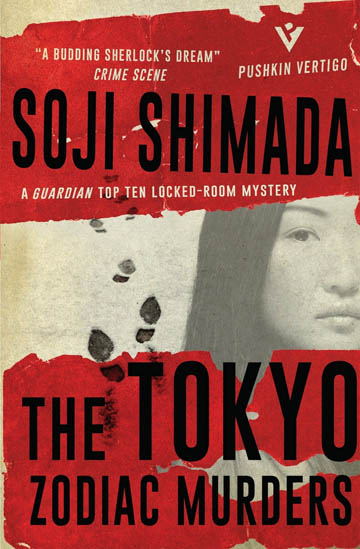

Tokyo Zodiac Murders, 1981

Tokyo Zodiac Murders, 1981Despite showing promise as a storyteller from a very young age, Shimada initially dreamt of becoming an artist. After high school, he studied at the Musashino Art University, a private university in Tokyo, where he studied commercial design.

After trying out various jobs as a musician, and truck driver for instance, he decided in his late twenties to write a novel when he turned thirty, something he subsequently did with amazing impact.

That novel – his very first, The Tokyo Zodiac Murders was shortlisted as a finalist for the Edogawa Rampo Prize, a prestigious award for unpublished works in 1981, helping him win his first publishing contract, but not the prize itself.

The Tokyo Zodiac Murders, which has recently been re-published in English translation, features a stunning twist based on an actual crime committed in the 1970s by a group of ingenious Japanese counterfeiters.

- Shimada’s debut novel triggered a publishing boom and helped define a new genre

The publication of The Tokyo Zodiac Murders generated a boom in whodunnits in Japan and a reappraisal of the out-of-favour and often derided genre, known locally as honkaku mysteries, classical or orthodox mysteries, which had often been looked down on by Japan’s literati.

Tokyo Zodiac Murders by Rivages, 2013

Tokyo Zodiac Murders by Rivages, 2013So much so that The Tokyo Zodiac Murders published in 1981 spawned a new genre or sub-genre known as shin-honkaku neoclassical mysteries, helping rebrand and popularise the whodunnit in all its brilliant creative forms.

The sensational success of Shimada’s first two novels, The Tokyo Zodiac Murders, and Murder in the Crooked House, put a lot of pressure on Shimada as a writer, but he has never looked back, always believing his best work is yet to come.

Having found fame, Shimada moved to Los Angeles in 1993, where he stayed with his wife for 16 years bringing up their daughter and honing his craft as a professional and prolific writer of fiendishly clever crime fiction.

Shimada is probably best known for his two detectives, the grumpy guitar-playing amateur part-timer Kiyoshi Mitarai and the full-time professional rugby-loving detective Takeshi Yoshiki and their series. His works have been adapted for film, television and manga.

- His debut novel, ‘The Tokyo Zodiac Murders’, is now ranked as one the best ever written

The Tokyo Zodiac Murders is now ranked internationally as one of the very best of its genre ever written. Adrian McKinty, the Irish crime writer, for example, placed it at number two on his list of the all-time greatest locked-room mysteries in an article in The Guardian, ahead of books by Agatha Christie (1890-1976) and Ellery Queen (1905-1971), and many other highly respected and widely read authors.

Shimada, now based back in Tokyo, writes a new full-length novel most years and has a growing reputation in Asia and in China in particular, where he has a large following on social media, and his works are being made into Chinese language films.

There is also a Shimada Prize run in his honour in Taiwan focused on nurturing a new generation of mystery writers in Asia, something that Shimada has done very successfully already in Japan, which has even led to one of the new generation of Japanese mystery writers naming his detective Kiyoshi Shimada in a homage to Japan’s trendsetting Man of Mystery.

In 2009, Shimada was awarded the prestigious Japan Mystery Literature Award in recognition of his lifelong contribution to the genre.

- Soji Shimada

Soji Shimada born in Fukuyama City, Hiroshima in 1948, showed promise as a storyteller from a very young age. Initially, it was just telling his younger brother bedtime stories, as they lay next to each other in their futons in the room they shared, obviously these were mostly detective and adventure stories.

His storytelling audience quickly outgrew his home extending to his friends at primary school.

At lunchtime the children, at his school, grouped their desks together in their classroom where they sat with their friends and ate lunch at islands of desks. A bored Shimada started telling his friends detective stories mimicking the stories he was reading in books such as those in Edogawa Rampo’s series for young readers the Boy Detectives Club Novels. However, the young Shimada set his fantastic tales in the grounds of their school.

As it was hard to improvise a new story each day Shimada starting preparing stories in advance in a notebook. This is how Shimada’s prolific career as a writer actually started, even though it wasn’t until his late twenties that he decided to try to pursue a career as a full-time professional author.

This youthful storytelling also inspired the first crime fiction boom Shimada was responsible for. Other children at the other desk-islands in his classroom joined in leading to a mini storytelling boom and cross-class competition to tell the best detective and adventure stories.

Growing up Shimada read as many detective and science fiction books he could get his hands on. This included everything on offer at his school library, which was rather limited in range. He read the Japanese Holmes series for children and many other books.

He also recalls enjoying the science fiction writer Masao Segawa (1931-2011) and enjoying reading Jules Verne (1828-1905) in translation, and still today vaguely remembers the story lines of Verne’s De la terre à la lune (From the Earth to the Moon).

At high school Shimada’s interests broadened out to include music, art and sport. Shimada, who is now a Beatles-loving anglophile and what would probably be called a petrol-head in Britain, played right wing in his high school rugby team, for example. Despite all the early indications of his potential as a writer at this stage in his life Shimada dreamt of becoming an artist.

That said, being in the school rugby team was a positive and enjoyable experience for Shimada, which he eventually converted into one of his most successful series after he became a professional author. His tough no-nonsense detective Takeshi Yoshiki, the main character in one of his two major series, is a former rugby player.

After studying at Fukuyama Seishikan high school in Fukushima City, Shimada studied at Musashino Art University in Tokyo where he majored in commercial art and design.

- Japanese Editions

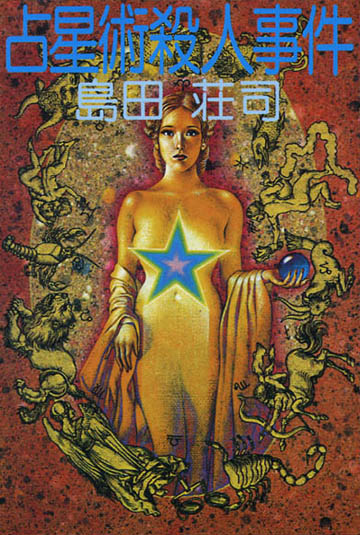

Senseijutsu Satsujin Jiken (The Tokyo Zodiac Murders), 1981

Senseijutsu Satsujin Jiken (The Tokyo Zodiac Murders), 1981 KM Series

KM Series Edogawa Rampo Prize nominee

Edogawa Rampo Prize nominee- Senseijutsu Satsujin Jiken (The Tokyo Zodiac Murders), 2013[Bunko]

Naname yashiki no hanzai (Murder in the Crooked House), 1982

Naname yashiki no hanzai (Murder in the Crooked House), 1982 KM Series

KM Series- Naname yashiki no hanzai (Murder in the Crooked House), 2016[Bunko]

Ihou no kishi (The Knight Stranger), 1988

Ihou no kishi (The Knight Stranger), 1988 KM Series

KM Series- Ihou no kishi (The Knight Stranger), 1991/1998[Bunko]

Mitarai kiyoshi no dansu (Kiyoshi Mitarai Dance), 1990story collection including: Yamataka bou no ikarosu (The Bowler-hat Icarus)/ Aru kishi no monogatari (A Certain Knight's Story) / Butoubyou (St. Vitus' Dance) / Kinkyou houkoku (Recent Report)

Mitarai kiyoshi no dansu (Kiyoshi Mitarai Dance), 1990story collection including: Yamataka bou no ikarosu (The Bowler-hat Icarus)/ Aru kishi no monogatari (A Certain Knight's Story) / Butoubyou (St. Vitus' Dance) / Kinkyou houkoku (Recent Report) KM Series

KM Series Kurayamizaka no hitokui no ki (The Man-Eating Tree of Kurayamizaka), 1990

Kurayamizaka no hitokui no ki (The Man-Eating Tree of Kurayamizaka), 1990 KM Series

KM Series Suishou no piramiddo (The Crystal Pyramid), 1991

Suishou no piramiddo (The Crystal Pyramid), 1991 KM Series

KM Series Memai (Vertigo), 1992

Memai (Vertigo), 1992 KM Series

KM Series Atoposu (Atopos), 1993

Atoposu (Atopos), 1993 KM Series

KM Series P no misshitsu (Locked Room“P”), 1999story collection including: Suzuran jiken (Suzuran Incident) / P no misshitsu (Locked Room“P”)

P no misshitsu (Locked Room“P”), 1999story collection including: Suzuran jiken (Suzuran Incident) / P no misshitsu (Locked Room“P”) KM Series

KM Series Roshia yuurei gunkan jiken (The Haunted Russian Military Ship), 2001

Roshia yuurei gunkan jiken (The Haunted Russian Military Ship), 2001 KM Series

KM Series Oboreru Ningyo (Drowning Mermaid), 2006story collection including: Oboreru ningyo (Drowning Mermaid) / Ningyo heiki (Mermaid Weapon) / Mimi no hikaru ko (The Boy with the Shining Ear) / Umi to dokuyaku (The Sea and Poison)

Oboreru Ningyo (Drowning Mermaid), 2006story collection including: Oboreru ningyo (Drowning Mermaid) / Ningyo heiki (Mermaid Weapon) / Mimi no hikaru ko (The Boy with the Shining Ear) / Umi to dokuyaku (The Sea and Poison) KM Series

KM Series UFO oodoori (UFO Boulevard), 2006story collection including: UFO oodoori (UFO Boulevard) / Kasa o oru onna (The Woman Who Folds Her Umbrella)

UFO oodoori (UFO Boulevard), 2006story collection including: UFO oodoori (UFO Boulevard) / Kasa o oru onna (The Woman Who Folds Her Umbrella) KM Series

KM Series

Riberutasu no guuwa (Allegory of Ribeltas), 2007story collection including: Riberutasu no guuwa (Allegory of Ribeltas) / Kuroachiajin no te (The Hands of Croatians)

Riberutasu no guuwa (Allegory of Ribeltas), 2007story collection including: Riberutasu no guuwa (Allegory of Ribeltas) / Kuroachiajin no te (The Hands of Croatians) KM Series

KM Series Seiro no umi 1 (The Clockwork Current 1), 2013

Seiro no umi 1 (The Clockwork Current 1), 2013 KM Series

KM Series

Seiro no umi 2 (The Clockwork Current 2), 2013

Seiro no umi 2 (The Clockwork Current 2), 2013 KM Series

KM Series Okujou no douketachi (Clowns on the Roof), 2016

Okujou no douketachi (Clowns on the Roof), 2016 KM Series

KM Series Torii no misshitsu: Sekai ni tada hitori no santakuroosu (The Shrine’s Secret Gate: The World’s Only Santa Claus), 2019

Torii no misshitsu: Sekai ni tada hitori no santakuroosu (The Shrine’s Secret Gate: The World’s Only Santa Claus), 2019 KM Series

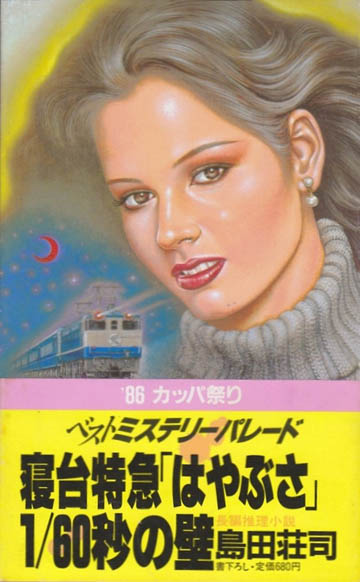

KM Series Shindai tokkyuu “hayabusa” 1/60-byou no kabe (Slumbering Limited-Express “Hayabusa” – The 1/60 Second Wall), 1984

Shindai tokkyuu “hayabusa” 1/60-byou no kabe (Slumbering Limited-Express “Hayabusa” – The 1/60 Second Wall), 1984 TY Series

TY Series

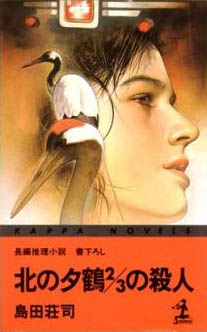

Kita no yuzuru 2/3 no satsujin (North Yuzuru 2/3 Murderer), 1985

Kita no yuzuru 2/3 no satsujin (North Yuzuru 2/3 Murderer), 1985 TY Series

TY Series

Yuutai ridatsu satsujin jiken (The Out-of-body Murder), 1989

Yuutai ridatsu satsujin jiken (The Out-of-body Murder), 1989 TY Series

TY Series

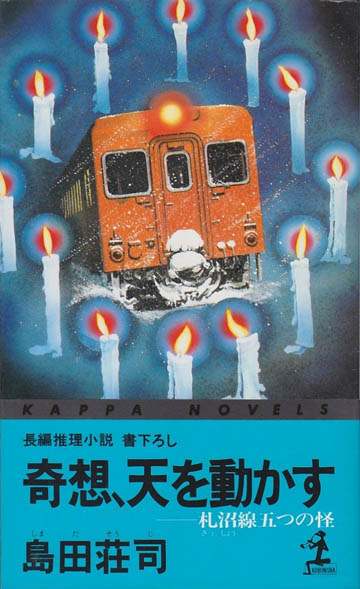

Kisou, ten wo ugokasu (Fantastic Idea: Moving Heaven), 1989

Kisou, ten wo ugokasu (Fantastic Idea: Moving Heaven), 1989 TY Series

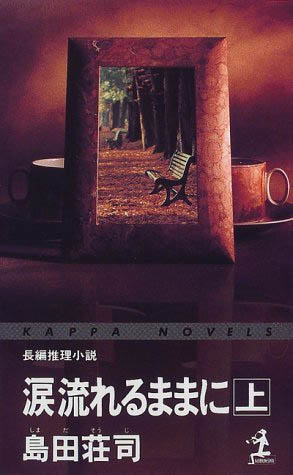

TY Series- Namida nagareru mama ni 1 (As Tears Flow 1), 1999[Bunko]

TY Series

TY Series - Namida nagareru mama ni 2 (As Tears Flow 2), 1999[Bunko]

TY Series

TY Series  Moukenrou kitan (The Mystery of The Blind Swordsman and The keep), 2019

Moukenrou kitan (The Mystery of The Blind Swordsman and The keep), 2019 TY Series

TY Series Shimada Soji Zenshu I, 2006story collection including: Senseijutsu Satsujin Jiken / Naname yashiki no hanzai / Shisha ga nomu mizu

Shimada Soji Zenshu I, 2006story collection including: Senseijutsu Satsujin Jiken / Naname yashiki no hanzai / Shisha ga nomu mizu Shimada Soji Zenshu II, 2008story collection including: Shindai tokkyuu “hayabusa” 1/60-byou no kabe / Uso demo iikara satsujin jiken / Izumo densetsu 7/8 no satsujin / Souseki to rondon miira satsujin jiken

Shimada Soji Zenshu II, 2008story collection including: Shindai tokkyuu “hayabusa” 1/60-byou no kabe / Uso demo iikara satsujin jiken / Izumo densetsu 7/8 no satsujin / Souseki to rondon miira satsujin jiken Shimada Soji Zenshu III, 2009story collection including: Kita no yuzuru 2/3 no satsujin / Takayama satsujn iki 1/2 no onna / Satsujion daiyaru wo sagase / Kieru “Suishou Tokkyu”

Shimada Soji Zenshu III, 2009story collection including: Kita no yuzuru 2/3 no satsujin / Takayama satsujn iki 1/2 no onna / Satsujion daiyaru wo sagase / Kieru “Suishou Tokkyu” Shimada Soji Zenshu IV, 2010story collection including: Kakuritsu 2/2 no shi / Saten no mameido / Natsu, jukyusai no shozo / Kakeitoshi

Shimada Soji Zenshu IV, 2010story collection including: Kakuritsu 2/2 no shi / Saten no mameido / Natsu, jukyusai no shozo / Kakeitoshi Shimada Soji Zenshu V, 2012story collection including: Kieru shanghai redii / Y no kouzu / Abashiri hatsu harukanari / Tenboutou no satsujin

Shimada Soji Zenshu V, 2012story collection including: Kieru shanghai redii / Y no kouzu / Abashiri hatsu harukanari / Tenboutou no satsujin Shimada Soji Zenshu VI, 2014story collection including: Mitarai Kiyoshi no aisatsu / Hirake! Kachidokibashi / Hai no meikyu / Doku wo uru onna

Shimada Soji Zenshu VI, 2014story collection including: Mitarai Kiyoshi no aisatsu / Hirake! Kachidokibashi / Hai no meikyu / Doku wo uru onna Shimada Soji Zenshu VII, 2016story collection including: Ihou no kishi / Kirisaki jakku・hyakunen no kodoku / Usodemo iikara yuukai jiken / Yotu ha zen no suzu wo narasu

Shimada Soji Zenshu VII, 2016story collection including: Ihou no kishi / Kirisaki jakku・hyakunen no kodoku / Usodemo iikara yuukai jiken / Yotu ha zen no suzu wo narasu Genshi (Phantom Limb), 2014

Genshi (Phantom Limb), 2014

Arukatorazu gensou (Alcatraz Illusion), 2012

Arukatorazu gensou (Alcatraz Illusion), 2012 Go-guru otoko no kai (The Terror of the Goggle-Fugitive), 2011

Go-guru otoko no kai (The Terror of the Goggle-Fugitive), 2011

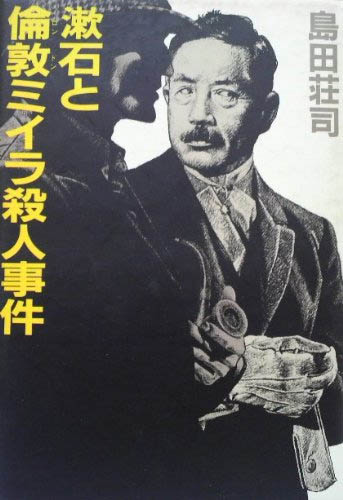

Souseki to rondon miira satsujin jiken (Soseki and London Mummy Murder), 1984

Souseki to rondon miira satsujin jiken (Soseki and London Mummy Murder), 1984- Souseki to rondon miira satsujin jiken (Soseki and London Mummy Murder), 2009[Bunko]

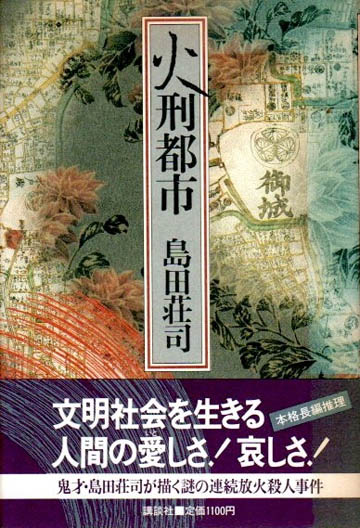

Kakeitoshi (The City of Death by Burning), 1986

Kakeitoshi (The City of Death by Burning), 1986

Natsu, jukyusai no shozo (Summer: The 19-Year-Old Portrait), 1985

Natsu, jukyusai no shozo (Summer: The 19-Year-Old Portrait), 1985

Akiyoshi jiken (Akiyoshi Incident), 1994

Akiyoshi jiken (Akiyoshi Incident), 1994- Akiyoshi Hideaki jiken (Hideaki Akiyoshi Incident), 2005[Bunko]

Miura kazuyoshi jiken (Kazuyoshi Miura Incident), 1997

Miura kazuyoshi jiken (Kazuyoshi Miura Incident), 1997

- English Editions

- One Love Chigusa, 2020Red Circle Minis [Paperback]

- Murder in the Crooked House, 2019

The Tokyo Zodiac Murders, 2005

The Tokyo Zodiac Murders, 2005- The Tokyo Zodiac Murders, 2015[Paperback] <!--

- Other Editions

- Tokyo Zodiac Murders, 2010French Edition

- Tokyo Zodiac Murders, 2013French Edition [Paperback]

- Gli omicidi dello zodiaco (The Tokyo Zodiac Murders), 2019Italian Edition [Paperback]

Tokijskij Zodiak (The Tokyo Zodiac Murders), 2019Russian Edition

Tokijskij Zodiak (The Tokyo Zodiac Murders), 2019Russian Edition Senseijutsu Satsujin Jiken (The Tokyo Zodiac Murders), 2020Ukrainian Edition

Senseijutsu Satsujin Jiken (The Tokyo Zodiac Murders), 2020Ukrainian Edition Torii no misshitsu (The Shrine's Secret Gate), 2019Taiwanese Edition

Torii no misshitsu (The Shrine's Secret Gate), 2019Taiwanese Edition Ihou no kishi (The Knight Stranger), 2009Taiwanese Edition

Ihou no kishi (The Knight Stranger), 2009Taiwanese Edition- Ihou no kishi (The Knight Stranger), 2013Taiwanese Edition [Bunko]

- Asuka no garasu no kutsu (Asuka's Glass Shoe), 2000Taiwanese Edition [Paperback]

- Naname yashiki no hanzai (Murder in the Crooked House), 1999Taiwanese Edition [Bunko]

Sensei jyutu Satsujin Jiken (The Tokyo Zodiac Murders), 1988Taiwanese Edition

Sensei jyutu Satsujin Jiken (The Tokyo Zodiac Murders), 1988Taiwanese Edition Tengoku kara no judan (Guns from The Heavens), 1996Taiwanese Edition

Tengoku kara no judan (Guns from The Heavens), 1996Taiwanese Edition- Mitarai Kiyoshi no aisatsu (The Greetings of Kiyoshi Mitarai), 2013Korean Edition [Paperback]

Natsu, jukyusai no shozo (Summer: The 19-Year-Old Portrait), 2011Korean Edition

Natsu, jukyusai no shozo (Summer: The 19-Year-Old Portrait), 2011Korean Edition Kisou, ten wo ugokasu (Fantastic Idea: Moving Heaven), 2011Korean Edition

Kisou, ten wo ugokasu (Fantastic Idea: Moving Heaven), 2011Korean Edition Ihou no kishi (The Knight Stranger), 2010Korean Edition

Ihou no kishi (The Knight Stranger), 2010Korean Edition Naname yashiki no hanzai (Murder in the Crooked House), 2009Korean Edition

Naname yashiki no hanzai (Murder in the Crooked House), 2009Korean Edition Ryugatei jiken 1-2 (Ryugatei Murders 1-2), 2008Korean Edition

Ryugatei jiken 1-2 (Ryugatei Murders 1-2), 2008Korean Edition- Senseijutsu Satsujin Jiken (The Tokyo Zodiac Murders), 2006Korean Edition [Paperback]

Majin no yuugi (The Devil's Revelry), 2006Korean Edition

Majin no yuugi (The Devil's Revelry), 2006Korean Edition Senseijutsu Satsujin Jiken (The Tokyo Zodiac Murders), 2009Thai Edition

Senseijutsu Satsujin Jiken (The Tokyo Zodiac Murders), 2009Thai Edition Ihou no kishi (The Knight Stranger), 2009Thai Edition

Ihou no kishi (The Knight Stranger), 2009Thai Edition- Pembunuhan di Rumah Miring (Murder in the Crooked House), 2020Indonesian Edition [Paperback]

Senseijutsu Satsujin Jiken (The Tokyo Zodiac Murders), 2019Chinese Edition

Senseijutsu Satsujin Jiken (The Tokyo Zodiac Murders), 2019Chinese Edition- Okujou no douketachi (Clowns on The Roof), 2019Chinese Edition [Paperback]

- Shinshindo sekai isshu (Tales from Around The World: Short Story Collection), 2016Chinese Edition [Paperback]

- Mitarai kiyoshi no dansu (Kiyoshi Mitarai Dance), 2013Chinese Edition [Paperback]

- Go-guru otoko no kai (The Terror of the Goggle-Fugitive), 2013Chinese Edition [Paperback] <!--

- Teito eisei kidou (ooo EN ooo), 2015Chinese Edition [Paperback]

- Tengoku kara no judan (Guns from The Heavens), 2013Chinese Edition [Paperback]

- Inubou satomi no bouken (ooo EN ooo), 2013Chinese Edition [Paperback]

- Toumei ninngenn no naya (ooo EN ooo), 2013Chinese Edition [Paperback]

- Natsu, jukyusai no shozo (Summer: The 19-Year-Old Portrait), 2013Chinese Edition [Paperback] -->

Natsu, jukyusai no shozo (Summer: The 19-Year-Old Portrait), 2016Chinese Edition

Natsu, jukyusai no shozo (Summer: The 19-Year-Old Portrait), 2016Chinese Edition Oboreru ningyo (Drowning Mermaid), 2018Chinese Edition

Oboreru ningyo (Drowning Mermaid), 2018Chinese Edition Saigo no dinaa (The Last Dinner), 2017Chinese Edition

Saigo no dinaa (The Last Dinner), 2017Chinese Edition- Asuka no garasu no kutsu (Asuka's Glass Shoe), 2011Chinese Edition [Paperback]

- Ranuki kotoba satsujin jiken (Words Without “Ra”), 2010Chinese Edition [Paperback]

- Yuutai ridatsu satsujin jiken (The Out-of-body Murder), 2010Chinese Edition [Paperback]

Ihou no kishi (The Knight Stranger), 2009Chinese Edition

Ihou no kishi (The Knight Stranger), 2009Chinese Edition- Hikaru tsuru (The Shining Crane), 2011Chinese Edition [Paperback]

- Memai (Vertigo), 1991Chinese Edition [Paperback]

- Kakuritsu 2/2 no shi (A 2/2 Chance of Death), 1991Chinese Edition [Paperback]

Prize-winning

Prize-winning Prize nominee

Prize nominee Adapted for Film/TV

Adapted for Film/TV There are a total of 30 titles in the Detective Kiyoshi Mitarai Series (KY)

There are a total of 30 titles in the Detective Kiyoshi Mitarai Series (KY) There are a total of 16 titles in the Detective Takeshi Yoshiki Series (TY)

There are a total of 16 titles in the Detective Takeshi Yoshiki Series (TY)- In Japan there are two major book formats tanko-bon (Tanko) and bunko-bon (Bunko). See Factbook for explanation. The smaller images above are of the Bunko Editions, small-format paperbacks.

- Readers:

I write for the reader. When I first started writing, I had the image of a fanatical fan of so-called honkaku (classical or orthodox) mysteries in mind when I wrote. In a sense, I felt as if I was submitting a research paper or a thesis to an expert panel for their review.

At that time, social realism in the style of authors like Seicho Matsumoto (1909-1992), dominated the Japanese literary scene, and honkaku mysteries based on logic and deduction, weren’t held in high regard, falling outside the interests of the critics.

It was as if a spell had been cast on publishing and society, and even though powerful works were still being written because they were viewed as honkaku mysteries or mere classical whodunnits, they were, back then, simply ignored. It was a type of village mentality, with insular rules governing tastes, not the quality of what was being written, and books just weren’t appraised or reviewed.

Looking back at it now, it sounds odd almost like an Aesop’s fable, but that is really how it used to be. So you couldn’t simply target general readers when writing mysteries and detective stories.

Of course this phenomenon was all based on a misunderstanding. Let me try to explain. Before Seicho Matsumoto appeared on the scene, Edogawa Rampo’s (1894- 1965) works labeled as erotic-grotesque (eru-guro) fiction, fashioned in a similar style to Kibyoshi (yellow-cover) illustrated books from the Edo Period (1603-1868), which were identified by their yellow covers, were extremely popular.

Consequently, mystery writers were looked on with scorn and distain by Japan’s literary circles, and authors of so-called Jun-bungaku, pure literature.

What swept this all away was Seicho Matsumoto-style social realism. There was a rebellion against the erotic and the grotesque. Sadly, the literati and readers made no distinction, and mysteries and honkaku mysteries were included in this backlash and swept aside. Nevertheless, the value of crime fiction written by Seicho Matsumoto based on ordinary lives and social realism, was understood and appreciated.

It is interesting that it was young women that changed everything. Delving into the relationships between famous detectives and their assistants, and depicting these relationships, for example, as the dynamic or relationships between two gay men, helped generate a new boom and brand new enthusiasm, creating parodies, manga, booklets and chapbooks. This gradually brought an end to the phenomenon I have just described.

This was a total surprise for everyone including me, as we never imagined or expected that these types of readers could become part of our core audience or would even consider reading honkaku mysteries, and that these unexpected individuals would end up reading so passionately.

Nobody could have predicted this kind of thing happening, and I don’t think this would ever happen in the West. It’s probably down to Japan’s peculiar anime culture.

There was another aspect of this phenomenon, a secondary one that also broke new boundaries. They liked my sleuth Kiyoshi Mitarai, and my series featuring him became very popular amongst these women, even though at first I didn’t expect them to be able appreciate or understand the logic and the startling acrobatics, designed to surprise, in my narratives.

However, the characters that feature in books seem to have resonated with them, and they fell in love with them, and they even appeared to have learnt a few new things from my books.

What I am saying is that they really understood them, which was something totally unexpected for me.

As soon as I understood this, I started to really write for a much more general audience, without considering age or gender, and not just being fixated with fanatical mystery fans.

During the time when parody manga by young women were first appearing, I was asked if my protagonist sleuth Kiyoshi Mitarai was actually me! Many others seemed to have same question in their mind, even though they didn’t dare ask and kept the question to themselves.

I always answered ‘no’ to that question. Saying that Kiyoshi Mitarai is such an eccentric. He is super-smart, but is a rare individual that finds social interaction hard and isn’t good at cooperating well with the people around him. He also seems to show little interest in women.

That’s why so many gay parodies have been made about him. I then added, if I ended up like that it would really be the end. The lady who asked the question laughed with a knowing expression and didn’t ask any more questions.

Looking back at the mid-stage of my career as a writer, I was interested in the exoneration of people wrongly convicted of crimes, so-called miscarriages of justice. Even today I am still in touch with some individuals on death row. Some of my friends who were active in this area alongside me have often pointed out that I am similar to another of my fictional detectives, Takeshi Yoshiki from another of my popular series. Takeshi Yoshiki compared to Kiyoshi Mitarai probably has slightly more common sense and empathy.

So I would explain it like this. The relation between Kiyoshi Mitarai, Takeshi Yoshiki and myself are like a right-angled triangle. The distance between Takeshi Yoshiki and myself is 3, Kiyoshi Mitarai and myself is 4, and Kiyoshi Mitarai and Takeshi Yoshiki 5. Making Kiyoshi Mitrarai and Takeshi Yoshiki distinct.

Since becoming a writer I intentionally avoided putting myself into the personalities of the lead characters in my detective stories, as I feared that if I did this, the worlds my characters inhabit might be limited.

I think this is a trap many writers fall into. But even if this is your intention your personality will still end-up creeping into your works anyway, but it is important to keep this as negligible as possible.

Look at Sherlock Holmes, for example. He became a beekeeper in his later life, and this is something that really makes you sense the author, Sir Arthur Conan Doyle (1859-1930) himself. This tendency gradually started appearing in his work, when Britain was at war with Germany and continued afterwards.

However, I think Sherlock Holmes was at his brightest and best when making a big fuss, poking at dead bodies with a stick, or when he mistakenly thought he had invented a reagent which could detect a drop of blood diluted in a litre of water. (This invention was probably a mistake because we never get to see it again in any of his cases afterwards.)

Unlike Sir Arthur Conan Doyle with his common sense, Sherlock in that period, was an eccentric oddball and completely distinct from the author that created him.

I used to look at comments, but not anymore. The comments that stood out and left an impression were the strange, misguided and awful ones.

Ever since I have become involved with literary prizes and having to appraise and comment on, as well as select, works by others, I have as far as possible tried to focus on the positives, looking for the strengths and beauty in a work, and when I need to criticise, I only do so if I see there is a point to my criticism that is constructive. And will improve the quality of work if my advice is followed. I never criticise without providing concrete advice.

The same holds true for me if someone criticises my work or makes suggestions. I will listen to them sincerely. Generally speaking, people who are capable of giving proper and good advice will never be unnecessarily harsh, but calmly logical.

Most of the unnecessary harsh criticism usually comes from those who just want to show off or intimidate. And this type of criticism has limited benefit in terms of improving a work, or the broader genre itself.

As I mentioned, the dominance of Seicho Matsumoto’s school of social realism was so prevalent for so long time it turned many against the honkaku mystery genre. Mystery fans tend to see and talk about stories through a given perspective with defined formulas, pigeon holing them, and this is especially so for honkaku mysteries.

However, mystery writers need to explore and write beyond these expected formulas, breaking precedents, otherwise the genre will become a formulaic shell. It needs to develop, to have a future.

- Books:

This has been raised by many readers in Asia before. I think the important ones are The Tokyo Zodiac Murders and the next would be Murder in the Crooked House. The fist of these is my very first novel, my debut work, and the other is my second novel.

In the first decade after my debut, I didn’t want to consider that these first two works of mine were my very best works and resisted naming them as my representative works, as I felt that I would never progress as a writer if I thought that.

This would also make my 40 years of writing after their publication feel meaningless.

However, I have changed my stance. I would recommend reading these two first and if you like them, then move on to read my other books, which I hope you will read one after another.

All my books that followed the first and second, are completely different, but they aren’t inferior, and I can confidently say you will never be bored.

My debut novel The Tokyo Zodiac Murders deviated significantly from the approaches recommended by S.S. Van Dine (1888-1939) who made a huge contribution to the development and enrichment of the genre and its history.

The advancement of science and logic (which was once called philosophy) in the 19th century spawned works such as The Murders in the Rue Morgue by Edgar Allan Poe (1809-1849) and The Study in Scarlet by Sir Arthur Conan Doyle. Van Dain sorted through and analysed these and countless other published mysteries, and based on his own reading of more than 2,000 books, developed a set of definitive rules, almost like a judge presiding over a court trial, with a final verdict that guaranteed successful mystery writing, and should be followed.

What he proposed was very effective helping establish a golden age, but at the same time it led to the genre’s decline, as the central axis of a belief in science and reasoning was abandoned, and it placed limitation on what could be used.

The Tokyo Zodiac Murders, my debut novel, was a reaction to this and resisted Van Dine’s theories. It was written as a return to the style of Edgar Allan Poe and Arthur Conan Doyle. The mysterious and incomprehensible incident providing the background combined with the thorough use of science and the logic of deduction.

However, I think I was also influenced, especially about the mystery itself, by some of the excellent tales written by my Japanese predecessors. In that sense, the device, the trick, used in The Tokyo Zodiac Murders might look new for English and American readers even though the plot itself is pretty simple, and there are obvious clues to how to solve the puzzle, but readers who don’t notice these seeds will get a big surprise at the end.

In contrast, Murder in the Crooked House, my second novel, returned to Van Dine’s suggestions. It is a classic whodunnit where you see a strange collection of people coming together in a mysterious mansion covered with heavy snow, and unfathomable murders follow. A famous detective comes, and solves the riddles using clues, all of which have also been shared with the readers.

Although Murder in the Crooked House, follows Van Dine’s theories, the structure of the trick behind this story is as big as my first book. It is simple and obvious, and can be inferred, but may be unprecedented due to its simplicity and thus a one-of-a-kind story for both Japanese and Western readers.

An English language translation edition of Murder in the Crooked House, translated by Louise Heal Kawaii, was published by Pushkin Press in 2019.

I would recommend reading The Tokyo Zodiac Murders first.

Summer: The 19-Year Old Portrait (Natsu, 19-sai no shouzou) was adapted for film in China in 2017. It will be released in Japan 2018.

Sea of Stars (Seiru no umi), from the Kiyoshi Mitarai series, was adapted for film in Japan in 2016.

The Woman Who Folds Her Umbrella: UFO Boulevard (Kasa wo oru onna), also from the Kiyoshi Mitarai series, was adapted for TV in 2015.

Genshi, a stand-alone book, was adapted for film in 2014.

Gouguru Otokono Kai (The Terror of Goggle-Fugitie) was adapted as an NHK TV series.

Overnight Limited-Express train “Hayabusa” – The 1/60 Second Wall (Shindai tokkyuu “hayabusa” 1/60-byou no kabe) was adapted for TV.

Overnight Express Yuzuru 2/3 Murder (Kita no yuzuru 2/3 no satsujin) was adapted for TV.

The Out-of-body Murder (Yuutai ridatsu satsujin jiken) was adapted for TV.

Voice of the City (Toshi no koe) was adapted for TV.

Jigsaw and Zigzag (Ito noko to jiguzagu) was adapted for TV.

There might even be some other titles, which were made into television programmes or a mini-series, or films, which I can’t recall.

My dream-job, when I was young was a painter. I wanted to be an artist. I studied art at university. Hence, the artwork used on the covers of my books has always been of matter of great interest to me. I often interact with the designer, and I have even drawn rough sketches myself, and ask the designer to complete them.

There are many different book covers I like. But representative ones that reflect my taste, and are my favourite covers are probably the covers of the following books, created by these artists:

The City of Death by Burning (Kakeitoshi) by Katsuhiro Abiko

Atopos (Atoposu) by Tsutomu Toda

Vertigo (Memai) by Tsutomu Toda

Shimada Soji Collection by Tsutomu Toda

Miura kazuyoshi jiken (Kazuyoshi Miura Incident) by Yokoo Tadanori

The Locked Room of Pythagoras (P no misshitsu) by Takashi Kitami

Drowning Mermaid (Oboreru ningyo) by Koji Oka

The Fable of Libertas (Riberutasu no guuwa) by Koichi Sakano

I really don’t have a definite answer for that. Writing a novel is very different from making a hamburger. In the early stage of my career, I was prone to start writing without really thinking of the title, so I often had trouble in coming up with one, and asked my editors for advice.

Having said that, I already had the title before starting to write The Tokyo Zodiac Murders and Murder in the Crooked House. However, I thought the original title in Japanese for The Tokyo Zodiac Murders was banal and stylistically mediocre, so I tried to change it to The Magic of Astrology, but my editor resisted and the original title was kept.

As my career developed as a writer, the titles then tended to come first, before I started writing. Admittedly, that has something to do with the fact that I’ve become a seasoned writer, a veteran, and editors now tend to refrain from commenting. However, probably in most of the cases when a work is considered one of my best and has become famous, the title has come first.

This is really a tough question for me to answer. I used to write detective stories when I was in elementary school. If I can count from those days, you would have to say it took a very long time before I made my debut. However, I really only started considering seriously becoming a professional writer when I was in my mid-twenties. I decided I would write a novel when I turned thirty.

When my thirtieth birthday came, I quit all the jobs I had then, and started writing my first work The Tokyo Zodiac Murders, which I submitted to the Edogawa Rampo Prize. Although it was shortlisted, it didn’t win the prize. I was lucky enough that it was published quickly, and consequently I didn’t have to go through all the hardships that many writers do before making their debut.

As I have already mentioned, at the time, the spell that Seicho Matsumoto’s school of social realism cast still dominated Japanese literature so much so that, our genre, the honkaku mystery was marginalised for a long time.

It was a tough period, despite my debut novel being shortlisted for Edogawa Rampo Prize, I still wasn’t able to write honkaku mysteries such as the ones in the Kiyoshi Mitarai series, which came much later.

I had to write under the umbrella of so-called social realism, in the style of Seicho Matsumoto. That’s why I created the character, Takeshi Yoshiki, a police detective, as only a police detective could handle murder cases, and my original sleuth Kiyoshi Mitarai was an amateur investigator. That’s why I have two series with two different protagonists.

- Writing:

I have personally been involved in getting redress for individuals falsely charged or convicted, or for charges that are partially false, so-called miscarriages of justice, and quite a few of my novels have these experiences in their shadow.

There are also some Non Fiction books I have written that describe the details of actual cases, such as the Hideaki Akiyoshi Case and the Kazuyoshi Miura Case, and the activities involved in trying to overturn these miscarriages of justice.

In my novels when you read about false charges, attorneys and court hearings they are more or less based on my actual experiences. There are many examples of this in the Takeshi Yoshiki series, and there are also some in the Kiyoshi Mitarai series.

What proportion of my novels is based on my real personal experiences? I don’t know, as I am far too busy creating new works and haven’t analysed it. I don’t look back.

However, I do know that when I was, for a certain period, really passionate about campaigning for redress, and for false charges to be acknowledge as that: false, it helped generate a lot of content.

Again, like the last question it is hard to say. Each one of my many works has their own specific dramatic episodes. I think it would be correct to say they vary and contain different ideas.

I don’t have a specific place where I get my inspiration for writing. I wish I had such a place! It would be nice if there were. It would actually be like a dream, if there were a rock, that when I sat on it, all of a sudden brilliant ideas came to mind.

When I was involved in those cases of miscarriages of justice, I mentioned earlier, I would think about what was needed for the investigation to go well, and I tried to imagine where missing evidence might be found. In those situations ideas often came to me when I was travelling, or when I was on the road interviewing people, or in a court hearing, or when I was sitting in a meeting room at a law firm.

In the days when I rode a motorcycle, ideas sometimes came to me when I was on the motorway. Once I came up with a terrific idea for a medical related short story while an NHK Special was on television.

When I am reading my books or books by other authors I am sometimes interrupted with thoughts that in this situation I would do this.

As for The Tokyo Zodiac Murders, there was actually a real case of fraudulent banknotes, counterfeiters. It wasn’t a murder. But the approach they used planted an idea in my head, which became the trick for the plot.

Well, what I can say is that generally I haven’t experienced good ideas coming to me when I am sitting at my desk writing. If an author starts doing that it would probably make one’s work formulaic. The Goddess of creativity is very fickle.

Editors call me asking me to write on a certain topic or theme, explaining carefully the theme’s merits, to which I, at times, answer flatly no and hang up. But subsequently, just after hanging up, I come up with a great idea for the topic.

Because I still have a stock of ideas. I list up ideas and keep a growing stock of them. I think about that day in the future and what might happen if I have used up all of them. I want to tell all newcomers and all writers of honkaku mysteries that they should keep a running ideas list.

As I have already said, having an idea is one thing, while developing a theme into a work of fiction is a completely different activity. The two require totally different abilities. You need an open mind for ideas and you need to devote dedicated time for this, which is something most people don’t do.

When I started writing I thought I would never forget any of my good ideas. And it was probably true back then, but after working as a writer for ten years I started forgetting them. It’s because many similar ideas come to mind and your head gets filled up with countless ideas and concepts. If you write ideas down, briefly in a few sentences, they will always be there for you to see in the future, and they will become very valuable. Also if you don’t forget to write them down, you can read them back later, objectively, as if someone else had written them.

You can get very excited as a seemingly brilliant idea comes to your mind in the middle of the night and you write it down, and often you find next day when you re-read it that it isn’t in fact a big deal. And the opposite can also be true.

Even if you think it is a trivial idea combining it with other ideas on your list may in fact create a masterpiece. It might be a boring way to plan a murder, but allowing it to fail might make it interesting. You can’t do this without a list.

I think this is actually the secret to becoming a first-class writer. If you wait for an assignment, and only then come up with the concept, and develop it from there on you will produce good and bad works. This individual is the average writer.

First-class writers consistently produce good work of the highest quality. To be a first-class writer, you need a list full of good ideas, which allows you to use the best ones when needed. If you do this you will generate more highly regarded works, and you’ll be considered as a superb and powerful writer.

I don’t really know, especially the long novels. I really can’t concentrate on only writing nowadays because there are so many distractions.

I’m often asked to give a talk and I need to prepare for them. I also need to read works that have been submitted to literary prizes I am involved with. This can involve going all the way to Hiroshima for press conferences, giving interviews, appearing on TV talk shows and attending parties. I have a lot of work to do, which actually has nothing to with actually writing.

My sense is that it takes me several months to write a novel. In reality it probably takes two or three months, and probably longer for a substantial book. But I really don’t know.

Life always seems busy and hectic. I wish I could find more quiet time for writing.

I have made it a rule to write one full-length novel a year. For short stories, I don’t know. It also depends on the number of pages required; it is proportional, probably around a month. But if it is a short story of around 50 pages, it could be faster.

Some writers work on a short story in the morning and then go on to work on longer stories in the afternoon. For them, having lunch changes their mood, and acts as a switch between the two, preventing confusion.

However, this is not the case for me. I don’t write multiple full-length novels in parallel. If I work like that, the stories end up being mediocre as I haven’t given them enough thought, and they are likely to become overly simplistic from lack of attention and care. I’m not trying to say it’s impossible, but I believe working in parallel on several works is problematic, and it would be an easy way to waste good ideas and ruin a work with real potential as you end up making mistakes.

It might be possible on occasion for you to produce seven books in a year if you write them in parallel and they might even end up being good books, but it is unlikely they will masterpieces.

From my experience, I suspect, working in parallel like this makes it very difficult to produce two high quality books at the same time.

I can write anywhere, especially when I have a compact laptop.

I don’t only write in my study, but in coffee shops. I even can write at the dentist when having to wait for a long wait for my turn. When you’re engrossed in a story you’re working on, you can virtually write anywhere. On the other hand, I can’t write even in my study if my idea hasn’t taken shape, and I am still pondering about what to write.

No.

Currently, my preference is writing novels.

Yes I have, but as I later turned it into a novel. It didn’t actually end up as a film.

In Japan, film directors loathe the idea that the author of the original novel writes the screenplay. However, I think this is something that in the future should change.

In my view, films, including some of mine, tend to fall short of expectations compared to the original novels. In Japan, there aren’t really any screenplay writers who have detailed knowledge or a real understanding of honkaku mysteries.

The situation in England is different; something that is brilliant, and I envy.

- Reading:

Sadly, I can’t afford the time to read for pleasure anymore.

I have to read books as research for my own writing, and I also need to read the works submitted by contenders for the literary prizes I am involved in organising.

On top of that I write a new full-length novel every year and writing my own novel and a cluster of short stories every year – all of which keeps me extremely busy.

At the primary school I went to at lunchtime we pulled the desks together creating small islands where we sat in different groups. I would sit at one of these desk islands chatting with my friends. It was so boring, that one day I improvised a detective story, which I set in the grounds of our school. I spoke and everyone listened.

At that time my younger brother and I, the two of us, shared a bedroom, and I used to make up half-baked stories as we lay there in our futons at night. That’s how I was able to make something up like that.

To my surprise, my story went down very well and when the bell rang signally the end of lunch break I told everyone I would finish the story tomorrow. They loved it.

From that day onwards, I kept improvising, and telling stories until I ran out of ideas making it impossible to continue. I then started preparing a draft the day before scribbling in a notebook. And as I told my story every lunchtime, I kept glancing at what I had written in my notebook. It wasn’t easy and I ended up just reading my story out aloud as it was easier. This is how I lost my virginity as a storyteller and novelist.

I was heavily influenced by Edogawa Rampo’s series for young readers called Boy Detectives Club Novels (少年探偵団, Shonen tantei dan), in which there is a detective hero named Kogoro Akechi. He is the leader of a group of boy detectives. So my story telling was basically an imitation of this.

I’m not sure how much Edogawa has influenced me in terms of the writer I am today, as I was a mere child back then.

Around this time, I also read the Japanese Holmes series for children. Subsequently, I read the originals in translation. I think this had a big influence on me. I would say that Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s Holmes had the bigger influence on me.

And after that, I read a myriad of books, a countless number until I made my debut as a writer and I’m sure some of those books must have influenced me as well, but I can’t really say which ones, and I don’t think there was one in particular. Reading like this from a young age slowly influenced me allowing me to develop my own style.

Back to my primary school days, my storytelling on my classroom island kicked off a trend and a mini boom. Storytellers emerged on other desk-islands and a competition amongst the storytellers started. It was a very similar phenomenon to the boom after I made my debut as a professional writer that led to the creation of the new genre shin-honkaku, neoclassical mysteries. A forerunner, perhaps.

It was quite an experience for me.

They listened and I watched. One girl was totally absorbed in my story, at times looking disappointed and at times showing fear and anxiety. Their facial expression would change accordingly. It showed me the power of storytelling and the ideas hidden inside me, which increased my confidence as a storyteller.

When I was a junior high school student, I read all the science fiction (SF) books in the school library. So I must l have liked SF already back then. I especially liked the Japanese SF writer Masao Segawa (1931-2011). It was probably because he had a radio show at that time for children. I also liked Jules Verne (1828-1905) and vaguely remember the story lines of his De la terre à la lune (From the Earth to the Moon).

When I was in primary school, I read every single detective book in our school library. My favorites were Edogawa Rampo’s The Boy Detectives Club (少年探偵団 Shonen tantei dan) and the Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s Sherlock Holmes series for children. Well, maybe there just weren’t that many good titles back then!

- Japan:

This is my personal view, but it may be due to the fact that Japan was never colonised by another country. Countries and people like this are rare in world history. This gives them a particular attitude and sensibilities.

For a long time, more than two thousand years, policy regarding ethnicity didn’t change. Japan stayed unmixed, with no integration, and no or limited experience with the outside world. It was remote, and a place where it was hard to catch large whales. Japan was isolated.

That said, the Mongols tried to invade Japan in the 13th century. In the 16th century, the Age of Discovery, Portugal and Spain, and at the end of the 19th century Russia, all targeted Japan for invasion. Each time, luck came to Japan’s aid and this didn’t end up happening. In a sense, there seems to be something mystical about this.

It’s probably not totally mistaken to say that by the 19th century the entire planet with exceptions of Ethiopia, Thailand and Japan, had been colonised by the West.

Local diseases and epidemics probably put them off Ethiopia. Thailand only just kept its independence, as the French and the British had colonised countries on either side of it and were preoccupied by this, and it was probably easier for all if the country remained neutral. Japan was also lucky being furthest away, far from these Western nations, in the Far East.

Like England, Japan had its own chivalry and developed its own military in its own way. Did you know that Nobunaga Oda (1534-1582), a powerful feudal lord in the 16th century, was very enthusiastic about guns, which was the new weapon at that time? So much so that he formed the world’s largest artillery unit?

Matthew Calbraith Perry (1794-1858) who opened up Japan from its period of isolation in the mid-19th century apparently commented that the Japanese of that time were an amiable, humble and an obedient people, so much so that they could be deceived easily.

However, these same human beings when at war sacrifice their lives and become fierce and brave. This was explained to him by Philipp Franz Balthasar von Siebold (1796-1866), a German physician, botanist, and traveller, warning Perry to be careful.

After the Second World War, the educational system designed to reeducate Japan introduced by the Americans led to Japanese men losing this fighting spirit. Some might call it brainwashing. However, most features of Japan’s culture, to a certain degree, were maintained and continued to develop distinctively.

Both Perry, in Narrative of the Expedition of an American Squadron to the China Seas and Japan, and Siebold, who married a Japanese woman, repeatedly mentioned in their books that the Japanese people are different from others in Asia and China. Others such as the American Townsend Harris (1804-1878) and the Englishman Sir Rutherford Alcock (1809-1897), made similar observations.

They also mention that if you visit Japanese households, you see that even though most are simple and poor, they don’t appear to lack what they want. They felt the Japanese looked happy and content with their lives.

Interestingly, Perry is critical about the landscapes of China, but he praises Ryukyu (Okinawa) and writes that Japanese landscapes are picturesque.

Japan itself is a mystery.

Japan has become sloppy and is a nation that today bears little comparison to the Japan of Sir Rutherford Alcock’s day, when he visited Japan as the first British ambassador.

Roughly speaking, world history boils down to the fact that Western nations conquered and dominated the world. However, Japan wasn’t in this dynamic flow of history and I think this is still visible, and that many in the West recognise this fact today. That is the source of interest.

The Japan of today is different from the past, and from other nations. It is rare and our standpoint might look complicated, making Japan look strange from the outside. That’s Japan for you!

Despite Japan being strange, if you are interested in looking for things to learn and to study, Japan may have a lot to offer.

I’m sure there is much. As I mentioned in the answer to one of the previous questions, there are different things that give us our creative power.

I think Japan is still struggling to catch up in fields such as film, tennis, and athletics, and often lacks the basic levels of fitness or skills required. Also in motorsports, four wheel and two wheel, and the music, it remains hard to get to the required international levels of competitiveness.

However, in some areas such as the baseball and honkaku mystery writing, my field, we have real potential to be world-class – even though we are behind America and Britain in terms of slick humour and how women are depicted.

Talent is limited and therefore distribution across all areas is not uniform.

It is not well known, but Japan used to be at the highest level in mathematics in the 17th and 18th century.

In those days, there were many skilled geometricians. There was a custom in Japan known as Sangakuhonou, where mathematical problems were placed on wooden tables at shrines and temples as offerings, and as challenges for the congregants.

Some of these problems were at a very high level – so much so that solving them required the type of ability that might win you a Nobel Prize in the 20th century.

One example of the type of problem set might, for example have included four spheres of the same size cramped immobile inside a triangular pyramid, and the question: calculate the volume of the area unoccupied by the four spheres.

Japanese people love puzzle solving and such games. And this national mentality is a very good fit for the genre of honkaku mysteries, as both share the need for similar problem-solving skillsets.

I think Masahiro Abe (1819-1857) is very interesting. He was the Chief Senior Councilor (Roju) in the Tokugawa Shogunate during the Bakumatsu period (1853-1867), at the time of the arrival of Commodore Matthew Perry, the admiral in charge of the Pacific Fleet, who I have already talked about, who was on a mission to open Japan to the outside world.

If Abe hadn’t dealt with Perry well or misjudged the situation it is quite possible that Japan might have ended up being colonised.

Abe was a very competent and talented diplomat who built the basis of what might be called Japan’s cultural defense of today.

There is a territorial dispute from the Japan-Soviet days regarding the Northern Territories. This involves islands Japan claims. This is based on the boundary lines Abe drew at the end of Edo period. Since the Second World War and Japan’s defeat, Japan has been eagerly negotiating with Russian for their return.

As for Japan today, a name does not quickly come to mind. The current Prime Minster Shinzo Abe, who happens to have the same family name, is working hard for a new post-war period.

In Masahiro’s age Russia, France, Britain and America were perceived as the greatest threats to Japan, but now it’s the rise of China that is becoming the strategic threat.

It is a very difficult time to steer a nation, and foreign diplomacy is extremely complex in today’s environment, when we need to avoid being engulfed and contained by China.

I don’t think the threshold to enter the world of Japanese literature is particularly high. It may, in fact be easier than in other countries.

The Japanese book distribution system is based on a type of consignment sales system. It would take a long time to explain, but basically bookshops don’t buy books, they are placed in bookshops, and after a month unsold books are taken back by the publisher at no charge. The definition of this period has become loose, and longer and longer. It is now several months. This probably means that there are more opportunities for newcomers to get their titles into bookshops than in the West.

However, unlike the category that the genre mystery series falls within, it is harder for literary novels, so-called pure literature, jun-bungaku. For works of this nature, it is much more involved.

As I have already mentioned, the scientific revolution that gave birth to the type of classical mysteries written by Sir Arthur Conan Doyle or by Edgar Allan Poe didn’t happen in Japan. Their books were imported later and probably didn’t come to Japan until the country’s modernisation in the Taisho Period (1912-1926).

Edogawa Rampo, the so-called godfather of Japanese detective fiction and mystery writing, blended the mystery genre with pre-modern erotic and grotesque (ero-guro) style fiction linked to Japan’s Edo culture. This literary style was enthusiastically accepted and the detective story gained a strong foothold in Japan becoming very popular.

However Rampo’s successors mistakenly started including everything in their writing including pornography, which eventually led to the mystery genre and detective fiction being treated with disdain by established authors and Japan’s literati. Ever since then, the mystery and detective story, and literary fiction have been like oil and water.

The established elite literary circles labeled the Japanese mystery as a lowbrow pornography genre, one step below literary fiction. This view has become a long-term entrenched position, treating detective fiction as vulgar, and, in my opinion, continues and remains to a certain degree today. I think this kind of phenomenon can only be seen in Japan.

Almost all literary genres were actually western imports including the favoured naturalism of jun-bungaku, pure literature. It was triggered by Charles Darwin’s (1809-1882) Theory of Evolution, which shocked the world and inspired Guy de Maupassant (1850-1893) and Emile Zola (1840-1902) who paved the way for contemporary literature.

After Edogawa Rampo, Seicho Matsumoto whose style was much more modern came into the limelight, and his new style was seen as highbrow. In contrast, Rampo’s style was regarded as obsolete, and people often advocated that the Japanese literary trends should not revert back to the Rampo era styles.

It is ironic when you think about it. Both styles were invented during the scientific revolution in the West, and one shouldn’t be inferior or superior to the other. It is a nonsensical relationship.

Anyhow, the mystery and literary fiction became polar opposites. Nonetheless, Seicho Matsumoto was a key driving force in the mystery genre in Japan and was commercially very successful, to the extent that it’s said that about 80 percent of all the books during his era had an element of mystery in their narratives or could be classified as mysteries. Readers loved them.

In contract, literary circles loathed them, and avoided having any kind of mystery element in their narratives. This resulted in poor sales, and in the end only the masterpieces of the past remained popular. New books that resonated with reader were few in number.

This may be the reason that it is difficult for literary fiction to breakthrough in Japan, and for such authors to become part of the writing community.

Most of the important literary prizes for aspiring writers are in the mystery genre today, and the limited number of the prizes for literary fiction, pure-literature, jun-bungaku, are mostly for short stories. However, the winning short stories don’t sell that well even after they are published.

- Interests:

I have so many favourite films and I don’t think I can list them all. Science fiction, adventure, love stories, war movies, musicals, I could go on endlessly. I was once asked had to rank my favourite, honkaku mystery-related films. This is what I came up with:

No. 1 Sleuth

No. 2 Seven

No. 3 Purple Noon (French title: Plein soleil)

No. 4 The Night Visitor (Swedish title: Papegojan)

No. 5 The Negotiator

No. 6 Charade

No I haven’t, and I don’t think I would ever want to be in a film myself. I was once in a television drama in the background in a restaurant scene, without any lines of course.

It has been said that I like it, yes! Even though I haven’t been lately. I was in a band before. I can sing all of the Beatles songs. However, the number of their songs available for karaoke are rather limited, to my regret, and the key is too high! Actually you can see me singing on YouTube. I am singing in chorus with Yumeihito Inoue a fellow writer. It was for a TV talk show about the Beatles. It is my dream to become a bestselling author in the United Kingdom, and sing If I Fell (A Hard Day’s Night) in chorus, as a duet, with Paul McCartney. I can also sing some of Elvis Presley’s songs.

I’m quite fond of manga, but I don’t read much these days. My sleuth, Kiyoshi Mitarai, from my series was made into manga and serialised, and of course I read it with interest. The magazine publisher of the manga sent me copies. I had almost nothing to do with its creation though. There are some good manga based on a story about judicial scrivener, a type of judicial agent we have in Japan, and also one about baseball. I watched Your Name and In This Corner Of The World. I really enjoyed Toy Story and The Incredibles. They were exciting and amusing. I also enjoyed a recent British film, Loving Vincent, a rather unique animated film depicting the life of Vincent van Gogh, using oil painted animation.

I have never thought about that. It would be interesting to write about interesting figures like that, and I would love to direct such a film myself.

It is Kyoto. I recently got myself a workspace in Kyoto. Nishiki-Tenmangu Shrine in Kyoto is my favorite place to visit. I often go to the Starbucks nearby. It is nice to roam around Kyoto without a particular destination in mind, as the roads since ancient times are set out neatly in a grid. It makes it perfect for this. I also love the Kamo river, the Yasaka Shrine and Sannenzaka in Kyoko.

There is no such thing.

Even at this age it is hard for me to find the time I need without interruption to write. It is not just about projects that will make money.

What I am writing right now, I am doing half for fun, so it is all somewhat mixed up.

However, I don’t get stressed about it as I love my work.

I really don’t need a break. Even if I go on holiday, I am also thinking about and planning my next novel or reading materials or preparing a synopsis.

As you can see, I’m a workaholic.

I would have to select Sir Arthur Conan Doyle. However, his writing environment was very different from those of today. There were far fewer writers and books in his time whatever was written was welcomed. That also means there were works to read and reference.

He had to blaze a trail without having many other writers or works to refer to. I also assume there was no proofreading system back then as there are typographical errors here and there in his writing. If I’m not mistaken, there was a scene when John H. Watson’s wife called him by the name ‘James’. I would like to ask him about that!

It would also be very interesting if I could ask him how he approached his writing, and went about each new work, and see if it is different from how it is done today. I would like to talk to him about that.

I would also love to propose some ideas to him that he might use for Holmes.

As a matter of fact, I’ve written two parody books about Holmes, and I pretty much used up most of my ideas in those.

I would love to hear what he thought about S. S. Van Dine’s theories too, about his great influence on changing the course of mystery writing, making it more like a judicial trial style game.

Not at all, none!

I’m not the kind of person to be in a group. I prefer to be away from things that can create politics. I rarely go to literary parties.

The 100 metres sprint and the 400-metre relay.

If I can choose more, it would be the marathon and gymnastics as well as baseball. Figure skating, if you include the Winter Olympics.

- Life:

In the real world right? None, I guess.

The answer is of course writing mystery novels. There is no way I could stop doing that!

It might be the moment when I heard that my book The Tokyo Zodiac Murders was selected as No. 2 in The Guardian’s ranking The top 10 locked-room mysteries in 2014.

I thought it was some kind of a joke, outranking Agatha Christie (1890-1976) and Ellery Queen (1905-1982).

It was beyond my wildest dreams, and I can’t really describe how happy it made me feel. It was the moment when my biggest dream, became a reality. So many magical things have happened since then.

Pushkin Press offered to re-publish The Tokyo Zodiac Murders and they also decided to publish my Murder in the Crooked House.

My works had been widely read in Asia, but finally they have started gaining ground and recognition in the West.

My books will now be read in Sherlock Holmes’ country!

I really couldn’t ask more than that, it is the ultimate dream from my childhood.

I assume people who have succeeded in in his or her fields, and became a name, all have their own way of coping and managing stress, and it would be interesting to find out how each of them go about this.

As for myself, I don’t have anything special. If I’m forced to say something it would be to avoid having a very busy schedule, and making sure one has a stock of some pieces and ideas before you are asked to write something.

As for conference speeches, lectures and interviews, I don’t try to be the perfect speaker. Instead, I try to aim for at least a 70 percent level performance, not the perfect one, so that I don’t get nervous.

However, when I do get stressed, I try to fall asleep watching commentaries on international politics on YouTube, dozing off as I listen. Sound sleep keeps the doctor away, and illness!

Actually I rarely get stressed.

I don’t worry even if the books I am writing don’t sell well, and I don’t look at Internet rankings.

If you don’t drink and are careful with your money and not lavish, you don’t need a huge income.

Nothing much. Maybe it’s a smartphone. I don’t wear a watch anymore.

I try to walk every day. I often walk about the distance between one station and the next, find a café, go in and work there. I take a small laptop and printouts of my work to check. That’s my typical routine.

I rarely go out drinking, so I only take out about 30,000 yen from ATM. I usually carry between 30,000 – 50,000 yen in my wallet. I’m pretty frugal and only spend money at cafes or restaurants.

- Awards

- Testimonials

- News & Media