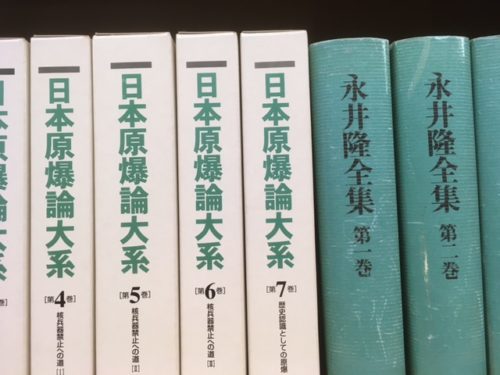

A collection of books about the atomic bombs on display in Nagasaki

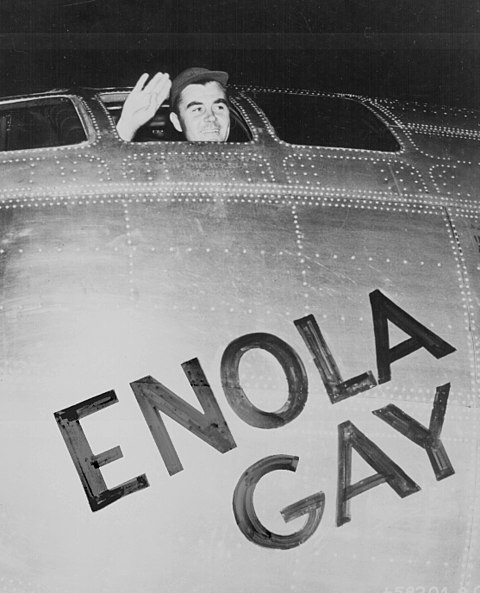

A collection of books about the atomic bombs on display in Nagasaki Paul Tibbets (1915-2007) waving from the Enola Gay’s cockpit before taking off for the bombing of Hiroshima. Image: Wikipedia

Paul Tibbets (1915-2007) waving from the Enola Gay’s cockpit before taking off for the bombing of Hiroshima. Image: WikipediaThe Pilot of the B-29 Superfortress, Paul Tibbets (1915-2007), which flew and subsequently dropped Little Boy – the name given to the atomic bomb used – discovered shortly after being assigned the mission of captaining this historic flight from Tinian in the northwestern Pacific, that his aircraft was nameless.

In what some have described as a literary act, he named the aircraft Enola Gay and had the name, his mother’s, painted on the side of the aircraft on August 5.

-

- Oh, Fatal Day – Oh, Day of Sorrow

Little Boy unit on trailer cradle in pit on Tinian, before being loaded into Enola Gay’s bomb bay. Image: Wikipedia

Little Boy unit on trailer cradle in pit on Tinian, before being loaded into Enola Gay’s bomb bay. Image: WikipediaHis mother Enola Gay Tibbets (1893-1983) was reportedly not at all pleased when she learnt on national radio that her name would now forever be entangled with this fateful mission, commanded by her son, when the news of the use of this new highly destructive weapon was broadcast the next day across America. Her son hadn’t informed her in advance of his decision to name the aircraft after her.

Enola had herself been named after a book, and its willful heroine, written in 1886 by Mary Young Ridenbaugh, Enola; Or, Her Fatal Mistake, which commences with the following poem:

Oh, fatal day – oh, day of sorrow,

It was no trouble she could borrow;

But in the future she could see

The clouds of infelicity.

Whether or not Enola; Or, Her Fatal Mistake, this 336-page novel actually falls within the canon of Atomic Bomb Literature is, however, probably an open question.

Decades later in the 1980s the British pop group Orchestral Manoeurvres in the Dark (OMD) released its celebrated anti-war song Enola Gay, with the lyric: “Is mother proud of Little Boy today?”

The single was a worldwide hit selling in the millions, becoming one of OMD’s signature songs, and cementing the name Enola and its destructive association in the minds of a new generation who hadn’t witnessed World War II first hand.

Many different genres of Japanese literature, storytelling and creative writing have been born on the back of these unique events. All of them adopting their narratives in myriad and often highly memorable forms.

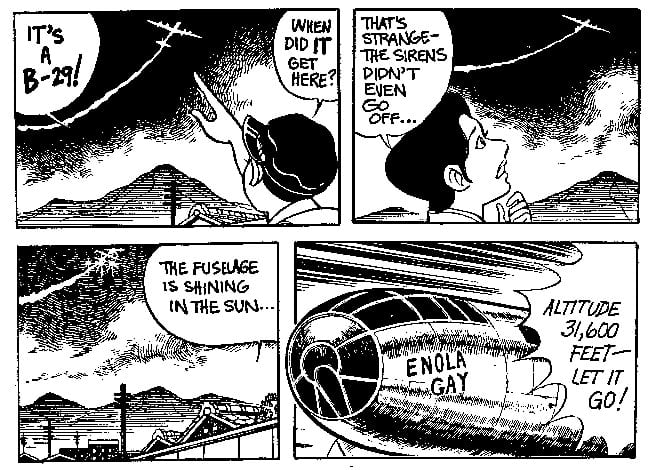

The best known works in the genre by Japanese authors are probably Black Rain by Masuji Ibuse (1898-1993) and the manga Barefoot Gen by Keiji Nakazawa (1939-2012), which tells the tale of a six-year-old boy Gen Nakaoka and other survivors trying to cope with the aftermath of the bombing of Hiroshima.

Barefoot Gen has been adapted for film, TV, theatre and anime – and multiple books have been written about it.

Image from English translation of Barefoot Gen by Keiji Nakazawa (1939-2012)

Image from English translation of Barefoot Gen by Keiji Nakazawa (1939-2012)Japanese atomic bomb writers include early survivors such as the poet Tamika Hara (1905-1951), an English graduate with a strong interest in Russian literature, who famously described the experience of witnessing an atomic attack: ‘as if the skin of the world around me was peeled off in an instant’.

That said, the Nobel Prize-winner Kenzaburo Oe, who wrote Hiroshima Notes and also edited the collection The Crazy Iris and Other Stories published on the 40th anniversary of the atomic bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, is another important example.

There are now several generations of atomic bomb writers. The first generation wrote mostly witness accounts, personal records and “first reactions” documenting first hand experiences. These are by and large emotive pieces that express disdain and disgust.

The second generation of writers generally try to provide a broader perspective, and the emerging third and fourth generations an even wider, and at times highly imaginative lens to frame the memories and narratives of the past.

And the debate on whether the use of nuclear weapons on these two occasions over Japan was justified continues in Japan, America and beyond.

-

- Memories and Narratives are Not History

The genre now includes a wide range of works such as Ray Bradbury’s (1920-2012) There will Come Soft Rains and Kamila Shamsie’s Burnt Shadows. Some people go as far as including some of the Godzilla films within its scope. Japanese-Americans and Japanese-Canadians, such as Joy Kogawa in her novel Obasan, have also grappled with the topic.

Some authors such as the bestselling children’s book author Miyoko Matsutani (1926-2015) in her work Two Little Girls Called Iida have used the date the August 6 as a plot device. In this story published in 1969 about a mother and daughter returning to Hiroshima, two girls are united through time by a special abandoned magical chair in a house where the calendar is stuck frozen on August 6.

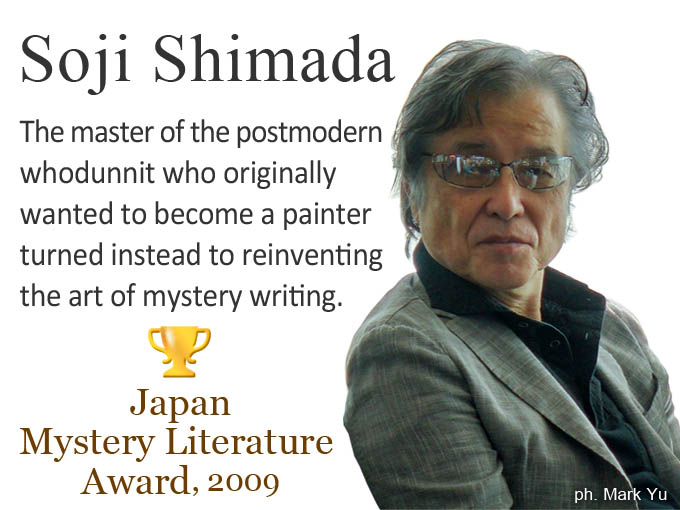

Another interesting and unusual example is, One Love Chigusa by Soji Shimada, a highly regarded mystery writer born in Hiroshima prefecture in 1948. While this book describes both the Hiroshima and Nagasaki bombs in its narrative, it is in fact a whodunit in the form of a science fiction tale set in a future Beijing in which Shimada explores themes of identity, loss and love in a heartless technological world.

One Love Chigusa was consciously published on 6 August 2020, the 75th anniversary of the Hiroshima bombing and written with a non-Japanese audience in mind. It does not, however, actually mention any hibakusha, and is therefore something of a fringe addition to the canon of Atomic Bomb Literature.

-

- Tales Recounted and Penned in the Thousands

The Japanese word for novel, shosetsu, entered the Japanese language via China in 1754 and is written using two letters or characters ‘small’ and ‘talk’ which highlights the historical importance and tradition of verbal storytelling in Japan.

Cover of Writing Ground Zero: Japanese Literature and the Atomic Bomb by John Whittier Treat an academic survey of some of the canon of Atomic Bomb Literature.

Cover of Writing Ground Zero: Japanese Literature and the Atomic Bomb by John Whittier Treat an academic survey of some of the canon of Atomic Bomb Literature.As these now ageing hibakusha pass away their children sometimes replace them taking on the role as narrator, often in soft small voices re-telling the tales, keeping the hibakusha stories alive as they talk about the days that must not be forgotten.

Diaries, poetry as well as more traditional forms of fictional and non-fictional accounts and records of the events have been penned in the thousands.

The breadth and extent of the associated literature is now so broad that it has created opportunities for academics to study and write about the genre as well as the actual historical events themselves.

Universities and colleges now even teach courses and modules on the genre such as Literature of World War II and The Atomic Bomb in Japan: History, Memory and Empire, which, for instance, is taught at Bowdoin College in Maine in the United States.

-

- Bungaku Maximus: Literature as a Nation’s Conscience

President Obama described the bombing of Hiroshima in his speech there in 2016 as a day when “death fell from the sky and the world was changed.” As the generation of individuals who personally experienced that day pass away, this unusual but important publishing genre may find a new freedom – creating a different literary legacy full of new contradictions that may very well capture the imagination of readers anew.

Hopefully, unlike the numerous literary responses, these two fateful acts will remain isolated, never to be repeated.

And as these memories evolve in newly written forms, the narrative fallout will never be allowed to fade away or decay.

Atomic Bomb Remembrance Hall in Nagasaki

Atomic Bomb Remembrance Hall in Nagasaki