The Bridge of the Gods (Shinkyo). Late 16th century Shino teabowl with bridge and house. Mary Griggs Burke Collection, gift of the Mary and Jackson Burke Foundation, 2015. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

The Bridge of the Gods (Shinkyo). Late 16th century Shino teabowl with bridge and house. Mary Griggs Burke Collection, gift of the Mary and Jackson Burke Foundation, 2015. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.T

he Holy Grail, the Cup of Christ, is a motif that features in the lore of King Arthur, Hollywood movies and bestselling novels. The word grail comes from the Old French word graal and Old Catalan and means: “a cup or bowl made of earth, wood or metal”.

Lord Tennyson (1809-1892), Dan Brown and many others have written stories about the quest to find it. It features in at least one opera by Wagner, as well as cropping up regularly in the visual arts, including the cinema.

Japanese film poster of the 1975 British film Monty Python and The Holy Grail. The film was a parody of the legend of King Arthur’s quest to locate The Holy Grail. It was the biggest grossing British film in the United States in the year of its release. Image Public Domain.

Japanese film poster of the 1975 British film Monty Python and The Holy Grail. The film was a parody of the legend of King Arthur’s quest to locate The Holy Grail. It was the biggest grossing British film in the United States in the year of its release. Image Public Domain.There can be little doubt that Christ and the narrative of Christianity have had a significant direct and indirect impact on Japanese literature and culture. But have authors and all the famous fictional heroes been searching in the wrong country for the Holy Grail?

Might the Holy Grail actually look much more like a traditional Japanese bowl, such as a Donburi, than the one depicted in films? And might it, in fact, be located somewhere in Japan?

The Nanteos Cup, now housed at the National Library of Wales. Photograph: National Library of Wales

The Nanteos Cup, now housed at the National Library of Wales. Photograph: National Library of WalesThe cup, which is said to have healing powers, had apparently been stolen while loaned to a sick women to aid her recovery.

This Cup looks remarkably like a Donburi. Nevertheless, it seems extremely unlikely that Christ’s Donburi, whatever that in fact might be, could have found its way to Japan.

The Christians…”are assigned a miserable crowded quarter” in the city, “like the ghetto of the…Jews” in the “Middle Ages”…”is virtually a prison.” “The police keep watch over them until they have drawn their last breath, and it is their business to remove the corpses, and dispose of them somehow,—no one knows where or how; but so that the name of”… “crucified one shall not be pronounced over their ashes.” Image and image caption from Japan and The Japanese Illustrated, 1874. Public Domain.

The Christians…”are assigned a miserable crowded quarter” in the city, “like the ghetto of the…Jews” in the “Middle Ages”…”is virtually a prison.” “The police keep watch over them until they have drawn their last breath, and it is their business to remove the corpses, and dispose of them somehow,—no one knows where or how; but so that the name of”… “crucified one shall not be pronounced over their ashes.” Image and image caption from Japan and The Japanese Illustrated, 1874. Public Domain.During this time Christians were often tortured and persecuted for their faith in much the same way as the Marrano Jews of the Iberian Peninsular were; and like the Jews, the Christians often practiced their religion in secret.

Fictional adventure stories from this period, in which Christians in Japan are described as The Hidden, feature in a series of books by Lian Hearn the first of which has the title: Across the Nightingale Floor.

S

ocial rules, rather than religion or an abstract system of morals are said to regulate and govern mainstream behavior in Japan. However, the creative communities in Japan have long held a fascination with marginalised groups that don’t play by the same rules and are thought to be freer to express their own individuality. Today such minority groups include Christians who make up less than one percent of the population.

Japanese popular culture exploits religious imagery and festivals in a pagan- like mass market manner.

Japanese popular culture exploits religious imagery and festivals in a pagan-like mass market manner. This is probably the case for almost all religions with perhaps the one exception of Buddhism, which was first adopted in Japan by its aristocrats during the Heian Period (794-1185), and reflects the more refined sophisticated side of Japan.

While ordering a delivery of Kentucky Fried Chicken (KFC), for example, for dinner on the 24th of December is not uncommon and popular. This bizarrely leads to Colonel Saunders morphing into Santa Claus and vice versa. Christmas Eve has recently become much more like our Valentine’s Day – and is Japan’s major Date Night – rather than a special spiritual night for many families.

Despite this, the search for Christianity and associated religious relics are actually drawing people to Japan.

Despite this, the search for Christianity and associated religious relics are actually drawing people to Japan. Travellers from South Korea (where there is a large Christian community) often as part of a cruise, are being taken on tours of the Christian sites in Nagasaki that are related to the Twenty-Six Martyrs of Japan.

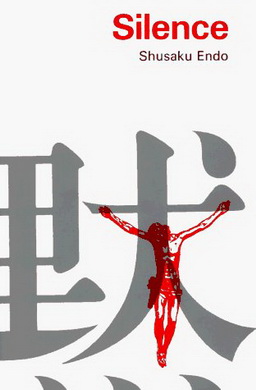

Cover of Chinmoku, Silence by Shusaku Endo, published in 1966.

Cover of Chinmoku, Silence by Shusaku Endo, published in 1966.Endo, who also wrote the brilliant and thought-provoking novel Deep River about a group of Japanese tourists, each of whom has a religious or spiritual experience while visiting India, is probably Japan’s best-known Catholic author.

The award-winning author and playwright of Crossing the River, Caryl Phillips, a big fan, says that before he commences a new writing project he always picks up and reads Silence. Interestingly, Endo did the same with Graham Greene’s books.

Ryunosuke Akutagawa (1892-1927), best-known outside Japan for his first published short story “In a Grove”, which was made into the award-winning film Rashomon by Akira Kurosawa, also wrote many short stories with Christian themes. “The Death of a Christian” (1918), “Black Robed Maria“ (1919) and “The Life of a Holy Fool” (1919) are good examples of some of these short stories. The Akutagawa Prize, a literary award, is named after him.

Surprisingly, Junichiro Tanizaki (1886-1965), who like Endo came very close to winning the Nobel Prize in Literature, also had a connection to the church. His grandfather – who he was particularly close to – was a member of the Eastern Orthodox Church.

Tanizaki is known today for his stories about sexual obsession, such as the Tattoer, and the type of narratives included in the novella The Bridge of Dreams, in which the narrator searches for his lost mother; a lost traditional Japan; and his lost childhood through a bizarre complex relationship with his stepmother: not for religious narratives. But by his own admission, the influence of seeing his grandfather praying and Christianity were important. Without it he claimed he wouldn’t have become a “feminist”.

Japanese road sign for the Tomb of Christ. Credit: jasohill, flikr.

Japanese road sign for the Tomb of Christ. Credit: jasohill, flikr.According to a local legend, Christ didn’t die on The Cross, but escaped to Japan where he became a rice farmer – no doubt with his own special Donburi – and lived until the age of 106.

The legend began in 1933 with the discovery of a Hebrew text in Japan about the life and death of Jesus. The existence of the alleged last resting place of Jesus in Japan might perplex, confuse and annoy many. But Japanese monasteries are already on some travel agendas alongside temples, shrines and sushi. One such destination is Japan’s first convent established in 1898 in Hokkaido where – unlike Belgium’s beer brewing monks – Trappistine candy butter is made and sold by the 80 or so nuns, that live and work there. The nuns face direct competition for their snacks, which support their “self-sufficient” way of life from monks at the Trappist Monastery nearby who make butter, jam and cookies.

L

eading Japanese authors have been influenced by Christianity and have expressed a fascination with the lives of missionaries in Japan; Japan’s Christian Century; and the search for meaning immediately after the Second World War. Despite being few in number these books and authors have made a lasting impact on Japanese literature.

In the background, a Roman Catholic cathedral on a hill in Nagasaki after the world’s second atomic bomb, Fat Man (containing a core of about 6.4 kg (14 lb) of plutonium), was dropped on 9 August 1945. The crew of the Bockscar, the B-29 bomber which dropped the bomb that exploded above the Urakami Cathedral, the largest Christian building in the region in the Japanese city with the largest Christian community, were all Christian. The bomb destroyed just under half of the city, killing an estimated 35,000 people and injuring 60,000, Source: War Department. Office of the Chief of Engineers. Manhattan Engineer District.

In the background, a Roman Catholic cathedral on a hill in Nagasaki after the world’s second atomic bomb, Fat Man (containing a core of about 6.4 kg (14 lb) of plutonium), was dropped on 9 August 1945. The crew of the Bockscar, the B-29 bomber which dropped the bomb that exploded above the Urakami Cathedral, the largest Christian building in the region in the Japanese city with the largest Christian community, were all Christian. The bomb destroyed just under half of the city, killing an estimated 35,000 people and injuring 60,000, Source: War Department. Office of the Chief of Engineers. Manhattan Engineer District.Other notable authors with similar influences include: Shiina Rinzo (1911-1973), Toshio Shimao (1917-1986), Ayako Miura (1922-1999), Sawako Ariyoshi (1931-1984) and Hisashi Inoue (1934-2010).

They wrote about: managing guilt while searching for love after surviving the atomic bomb; mental illness; sacrifice; abortion; domestic violence; and aging. Many of their works were dramatized for television and film. Three examples are: The Sting of Death, The Face of Jizo and Freezing Point.

The narratives they grappled with mirror the times they lived in and their values. The issues we face today are not dissimilar, but include new ones like: increasing income inequality; globalisation and the rise of Asia; living with technology in our digital age; and rapidly aging populations.

It has been said that Japan, an island nation exposed to the global winds of change that developed and modernized in its own particular manner, is the perfect location from which to observe and reflect on our rapidly changing world.

From this vantage point and juxtaposition a new generation of brilliant Japanese authors are writing the narratives of today’s Japan, our times, and their lives. Perhaps this is The Holy Grail to be found in Japan.

© Red Circle Authors Limited

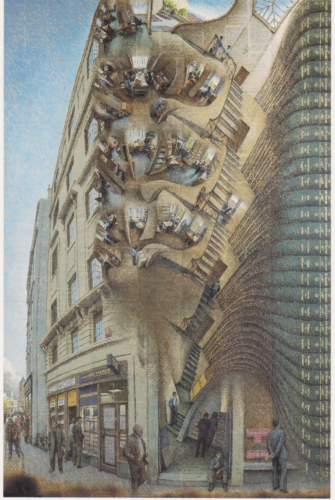

Seikando (second-hand) bookstore modelled on Matsumoto Castle, in Matsumoto, Nagano Prefecture, Japan. It was designed to look like the castle in the 1950s, a period when the real castle was under repair. Photograph: Public Domain

Seikando (second-hand) bookstore modelled on Matsumoto Castle, in Matsumoto, Nagano Prefecture, Japan. It was designed to look like the castle in the 1950s, a period when the real castle was under repair. Photograph: Public Domain