Photograph: www.petertasker.asia/

Photograph: www.petertasker.asia/I

never had much interest in Japanese TV commercials until a friend asked me to appear in one, for an eyewear retailer. What kind of people do this, I wondered, before discovering that I was following in a long and illustrious tradition.Shusaku Endo, for example, is the author of Silence, now a powerful film directed by Martin Scorsese. A Roman Catholic of an idiosyncratic bent, he delved into the deepest and darkest areas of human experience, from World War II atrocities to the torture of 17th century Christians.

Less well known is that Endo appeared in a Japanese TV commercial for Nescafe Gold Blend. He does some calisthenics in his garden, then sits down to a cup of refreshing coffee. “For men who understand the difference,” proclaims the slogan. So well received was the advert that it was re-broadcast in an updated form in 2008, 12 years after his death.

It’s hard to imagine a contemporary Western literary novelist doing something similar. Indeed, American author Jonathan Franzen snubbed TV host Oprah Winfrey when she chose his novel The Corrections for her viewers’ book club, so averse was he to having his work sullied by lowbrow commercialism.

Endo is by no means the only significant Japanese cultural figure to have fronted TV commercials. Ground-breaking film director Nagisa Oshima, flogged cockroach-repellent and air-freshener. Ryu Murakami, author of Coin Locker Babies, Audition and many other disturbing works, has peddled Suntory whiskey and Toyota cars and is currently engaged in a campaign for Epson printers. Younger pitchmen include novelists Keisuke Hada (Google Android) and Naoki Matayoshi (sauces, footwear, rail travel), both winners of the prestigious Akutagawa Prize for literature in 2015.

These creative people evidently felt that their status as artists would not suffer from involvement in corporate marketing campaigns. Presumably their audiences felt the same way. It’s also notable that Japanese advertisers considered serious novelists and controversial film directors to be suitable endorsers of everyday items. Franzen or British author Ian McEwan would never “lower themselves” by appearing in a TV commercial for insecticide, but neither would they be asked. As product pushers, they would be hopelessly ineffective.

The absence of taint appeals to the overseas celebrities who star in Japanese commercials but would never dream of doing the same at home. There is even a website, Japander, dedicated to their efforts. Amongst the unlikely marketers are Dennis Hopper (bath salts) and Yoko Ono who hocked instant noodles jointly with the long dead John Lennon in 2000.

- FROM LAUREATE TO LINGERIE

T

elevision commercials are different from other advertisements in that they bring the message and the messenger right into your living room. A bond of intimacy is created. Celebrities lose their “otherness” and become ordinary people selling ordinary products, working for money, just like the rest of us. Japanese TV commercials go out of their way to demystify their spokesmen. Oshima, director of the taboo-busting Empire of the Senses, prances around with a sappy grin on his face. A classical composer, a heavyweight economist and a Noh performer sip Nescafe like affable uncles.Japan is among the few rich countries that remain relatively unshaken by populist political movements, despite two “lost decades” of disappointing economic growth. There are many reasons for Japan’s social and political stability, but one may be the absence of a widening divide between the rulers and the ruled. In the U.S. and elsewhere, the “cognitive elites” – the political class, technocrats and intellectuals – no longer seem to understand or respect their fellow countrymen. Economically and culturally they inhabit separate worlds. Franzen’s snobbery toward potential readers foreshadowed Hillary Clinton’s dismissal of Donald Trump supporters as “a basket of deplorables.”

A healthier society may be one in which the cultural divide is much narrower, and serious artists are happy to be beamed into people’s homes to sell mass market items. After all some of the greatest American writers were comfortable with making product endorsements. Mark Twain marketed Conklin fountain pens and Ernest Hemingway and John Steinbeck lent their charisma to beer adverts. More recently Bob Dylan, winner of the 2016 Nobel Prize for Literature, has appeared in commercials for Chrysler cars and Victoria’s Secret lingerie – thereby showing that high artistic achievement can coexist with commerce and fun.

Endo, who did TV commercials for Canon and NEC as well as Nescafe, would probably approve heartily. I know I do.

© Peter Tasker

Peter Tasker: Special Contributor

Peter Tasker is a Tokyo based analyst and commentator on Japan and author of multiple Japan related books (fiction and non-fiction) including, most recently, "Japan’s Choices", which he wrote jointly with Bill Emmott, the former editor of The Economist. He currently works at Arcus Investment a company he co-founded.This article was originally published by the Nikkei Asian Review.

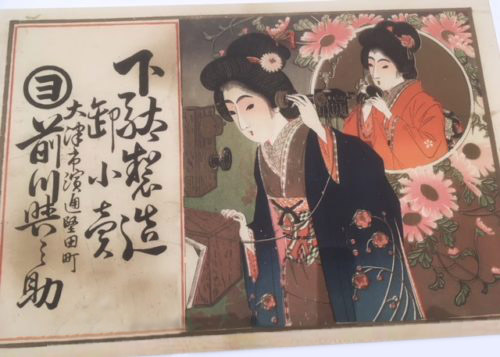

Creative advertising took off in Japan during its Edo Period (1603-1867). This Ebira poster, advertising geta (traditional Japanese wooden shoes) is on display at The Ad Museum Tokyo. Long before TV, Ebira posters were the most common form of advertising in Japan’s Edo and Meiji (1868-1912) eras. Advertisers and merchants would often select a picture, image or design they liked and add their own store name to the design using a name insertion printing technique. The images, like the celebrities in TV Ads, were selected to draw attention to a company's name or products by association with an image, a good luck charm or in this case two elegant ‘modern’ ladies talking on the phone. Photograph. Red Circle Authors Limited.

Creative advertising took off in Japan during its Edo Period (1603-1867). This Ebira poster, advertising geta (traditional Japanese wooden shoes) is on display at The Ad Museum Tokyo. Long before TV, Ebira posters were the most common form of advertising in Japan’s Edo and Meiji (1868-1912) eras. Advertisers and merchants would often select a picture, image or design they liked and add their own store name to the design using a name insertion printing technique. The images, like the celebrities in TV Ads, were selected to draw attention to a company's name or products by association with an image, a good luck charm or in this case two elegant ‘modern’ ladies talking on the phone. Photograph. Red Circle Authors Limited.