Fuminori Nakamura

“I’m bursting with story ideas. It’s not a talent, it’s more like a disease.”It is not surprising that Fuminori Nakamura has been dubbed the wunderkind of Japanese literature. He burst onto the Japanese literary scene with his critically acclaimed debut novel Ju (The Gun) in 2002 and within three years had won three of Japan’s major literary awards (the Shincho, Noma, and Akutagawa Prizes). He has gone on to be nominated for and win many more prizes. The Ōe Kenzaburō Prize, named after the Nobel Prize winner, for instance, which led two years later to the publication of his first novel in English, The Thief, by Soho Crime.

He won his first international prize in 2014, the NoireCon’s David Goodis Award, named after the American crime fiction writer, who exemplified the noire fiction genre. Nakamura is known outside Japan mostly as a crime writer who pens broody, dark, existential thrillers. This reflects the narratives of his five novels that have been published in English, one, The Thief, was selected by The Wall Street Journal for its list of the 10 best books published in 2012. He has published more than 13 novels in Japanese, three collections of short stories, and has also written serialized fiction for several leading Japanese newspapers.

“Nakamura, whose strategically withholding approach to filling in blanks invites conspiracy-minded readers to append whatever paranoid fantasies about government they happen to be dragging about on any given day,” The New York Times.

- Fuminori Nakamura

Fuminori Nakamura was born in 1977 in Aichi, Japan’s fourth largest prefecture, whose capital city is Nagoya. Nakamura started reading seriously and widely at high school, as an escape from student life. When he read the classics written, for instance, by Fyodor Dostoyevsky (1821-1881), Franz Kafka (1883-1924), Osamu Dazai (1909-1948), Albert Camus (1913-1960), Kobo Abe (1924-1993), Yukio Mishima (1925-1970) and Kenzaburō Ōe, the only living and one of only two Japanese winners of the Nobel Prize in Literature. Nakamura wanted nothing more than to follow their example and become a writer.

So after graduating from Fukushima University, a well-regarded national university, in 2000, where he studied sociology, he moved to Tokyo to pursue his long held dream.

The Gun, published in English by Soho Crime, 2016.

The Gun, published in English by Soho Crime, 2016.He initially supported himself by doing various part-time jobs before making his publishing debut two years later with his critically acclaimed novella Ju (The Gun), which won the Shinchō Literary Prize for New Writers.

Two years later his second novel Shakō (Shield Me from the Light) won the Noma Literary Prize. In 2005, he won the Akutagawa Prize for his novella Tsuchi no naka no kodomo (Child in the Ground), which was his third piece of writing to be nominated for the prestigious prize. He soon picked up the moniker “the wunderkind” of Japanese literature, as he was just 27 when he won the prize.

In 2010, his novel Suri (The Thief) won the Kenzaburo Oe Prize, named after the Nobel Prize winner who personally selects the winning title. There is no cash prize for the winning author, but the winning title is translated into English, French and German.

The Thief thus became his first novel to be translated into English and was published by Soho Crime, based in New York, in 2012.

- Nakamura gained international attention rapidly, winning his first literary prize outside Japan in 2014

International recognition came quickly. The Thief was a finalist for the Los Angeles Times Book Prize, and was and selected by the Wall Street Journal as one of the 10 best books published in 2012. Nakamura won his first non-Japanese literary award, two years later in 2014: the NoirCon’s David L. Goodis Award, named after the American crime fiction writer, who epitomized the noir fiction genre.

Soho Crime followed up on his successful first book in English by publishing; Evil And The Mask in 2013 (Aku to kamen no ruru), a tale of retribution targeting a boy raised to be “a cancer on the world” and Last Winter, We Parted (Kyonen no fuyu, kimi to wakare) in 2014, in which an aspiring writer interviews a convict on death row for murder and subsequently discovers a tangled group of individuals all connected through a craftsman of full-sized silicon sex dolls. The book follows a long Japanese tradition of using dolls as a narrative device to question our concept of reality and individuality.

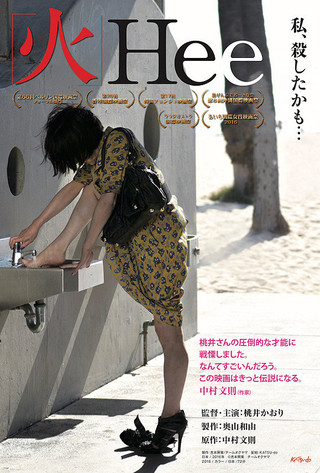

Japanese film poster for Hee (Fire) released in 2016.

Japanese film poster for Hee (Fire) released in 2016.His novels, often described as edgy and innovative, have been published widely in translation including in French, German, Chinese, Spanish and English. His work has also been successfully adapted for film and television.

The short story Hee (Fire), for example, was adapted and released as a film in 2016. It was directed by and stared Kaori Momi, who has won more awards than any other Japanese actress. The film was previewed at the Berlin Film Festival.

Nakamura is known outside Japan mostly as a crime writer who pens edgy, dark, existential thrillers. This reflects the narratives of his five novels that have been published in English. He and his work, as is the case with many new writers, building a reputation rapidly, are in fact much harder to pigeonhole.

He is on record saying: “as for how I describe what I write about, my novels are about the depths of the human heart – specifically, its darker side”. He also says he doesn’t mind how his books are labeled or defined – they have been referred to as literary fiction, mystery and crime – if people are reading them he is happy no matter their definition.

His favorite author is Dostoyevsky, and he still has great respect for the authors he read as a high school student, when he was growing up in Aichi Prefecture. He has published more than 13 novels in Japanese, three collections of short stories, and written serialised fiction for several leading Japanese national newspapers.

- Fuminori Nakamura

Fuminori Nakamura was born in 1977 in Aichi, Japan, whose capital city Nagoya is known for its medieval castle built between 1610-1619. Japan’s three best known samurai warlords Oda Nobunaga, Hideyoshi Toyotomi and Ieyasu Tokugawa, who collaborated and competed sometimes brutally in their epic struggle to unify Japan, were based there.

He has been an avid reader since he was at high school and before he went to Fukushima University, one of Japan’s prestigious national universities founded in 1946, where he studied sociology. He found life at high school hard and solitary.

His only escape was reading. One book that resonated, that he particularly enjoyed at the time, was No Longer Human (Ningen shikkaku), by Osamu Dazai (1909-1948), an author who seems to fascinate many of Japan’s successful contemporary writers. He found echoes of himself in the story of a reclusive young man who feels “disqualified from being human” but finds solace in literature. After graduating university he moved to Tokyo and took several part-time jobs to support himself until he made his highly successful literary debut in 2002.

- Japanese Editions

Retsu (The Line), 2023

Retsu (The Line), 2023 Jiyū taidan (Free Exchange), 2022

Jiyū taidan (Free Exchange), 2022 Ka-do shi (The Card Shark), 2021

Ka-do shi (The Card Shark), 2021- Ka-do shi (The Card Shark), 2023[Bunko]

Toubousha (The Fugitive), 2020

Toubousha (The Fugitive), 2020 Jiyū shikō (Freethinking), 2019

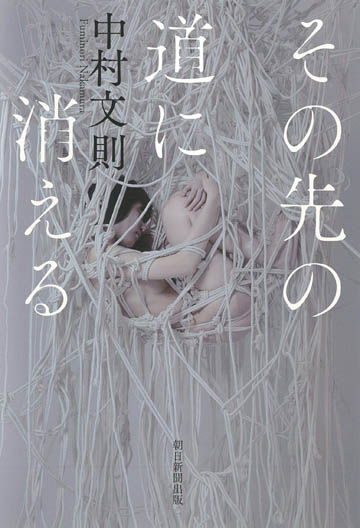

Jiyū shikō (Freethinking), 2019 Sono saki no michini kieru (Vanishes On the Road Ahead), 2018

Sono saki no michini kieru (Vanishes On the Road Ahead), 2018- Sono saki no michini kieru (Vanishes On the Road Ahead), 2021[Bunko]

R teikoku (R Empire), 2017

R teikoku (R Empire), 2017- R teikoku (R Empire), 2020[Bunko]

Watashi no shoumetsu (My Annihilation), 2016

Watashi no shoumetsu (My Annihilation), 2016 Prix des Deux Magots Bunkamura Prize

Prix des Deux Magots Bunkamura Prize- Watashi no shoumetsu (My Annihilation), 2019[Bunko]

Kyonen no fuyu, kimi to wakare (Last Winter, We Parted), 2013

Kyonen no fuyu, kimi to wakare (Last Winter, We Parted), 2013

- Kyonen no fuyu, kimi to wakare (Last Winter, We Parted), 2016[Bunko]

Meikyu (The Labyrinth), 2012

Meikyu (The Labyrinth), 2012- Meikyu (The Labyrinth), 2015[Bunko]

Okoku (The Kingdom), 2011

Okoku (The Kingdom), 2011- Okoku (The Kingdom), 2015[Bunko]

Aku to kamen no ruuru (Evil and the Mask), 2010

Aku to kamen no ruuru (Evil and the Mask), 2010

- Aku to kamen no ruuru (Evil and the Mask), 2013[Bunko]

Suri[suri] (The Thief), 2009

Suri[suri] (The Thief), 2009 Ōoe Kenzaburō Prize

Ōoe Kenzaburō Prize- Suri[suri] (The Thief), 2013[Bunko]

Sekai no hate (The Edge of the World), 2009

Sekai no hate (The Edge of the World), 2009- Sekai no hate (The Edge of the World), 2013[Bunko]

Nani mo ka mo yuutsuna yoru ni (One Melancholy Night), 2009

Nani mo ka mo yuutsuna yoru ni (One Melancholy Night), 2009- Nani mo ka mo yuutsuna yoru ni (One Melancholy Night), 2012[Bunko]

Saigo no inochi (Final Life), 2007

Saigo no inochi (Final Life), 2007

- Saigo no inochi (Final Life), 2010[Bunko]

Tsuchi no naka no kodomo (The Boy in the Earth), 2005

Tsuchi no naka no kodomo (The Boy in the Earth), 2005 Akutagawa Ryūnosuke Prize

Akutagawa Ryūnosuke Prize- Tsuchi no naka no kodomo (The Boy in the Earth), 2007[Bunko]

Akui no shuki (A Note of Malice), 2005

Akui no shuki (A Note of Malice), 2005- Akui no shuki (A Note of Malice), 2013[Bunko]

Shakou (Shield Me from the Light), 2004

Shakou (Shield Me from the Light), 2004 Noma Bungei Shinjin Prize

Noma Bungei Shinjin Prize- Shakou (Shield Me from the Light), 2010[Bunko]

Juu(The Gun), 2003

Juu(The Gun), 2003 Shinchō Shinjin Prize

Shinchō Shinjin Prize

- Juu(The Gun), 2006[Bunko]

- Juu(The Gun), 2012[Bunko]

Anata ga kieta yoru ni (The Night You Disappeared), 2015

Anata ga kieta yoru ni (The Night You Disappeared), 2015- Anata ga kieta yoru ni (The Night You Disappeared), 2018[Bunko]

Kyoudan X (Cult X), 2014

Kyoudan X (Cult X), 2014- Kyoudan X (Cult X), 2017[Bunko]

Ei (A), 2014

Ei (A), 2014 Madoi no mori: 50 sutooriizu (The Woods of a Delusion: 50 Stories), 2012

Madoi no mori: 50 sutooriizu (The Woods of a Delusion: 50 Stories), 2012- Madoi no mori (The Woods of a Delusion), 2018[Bunko]

- Sakka no koufuku (A Writer’s Mouthful), 2011Multi-Author Title [Bunko]

Kitsuenshitsu (The Smoking Room), 2007Multi-Author Title

Kitsuenshitsu (The Smoking Room), 2007Multi-Author Title- Dokusha toiu taiken (The Experience of Reading), 2007Multi-Author Title [Bunko]

- Sora wo tobu koi (The Love in the Air), 2006Multi-Author Title [Bunko]

- English Editions

The Rope Artist, 2023

The Rope Artist, 2023 My Annihilation, 2022

My Annihilation, 2022 Cult X, 2018

Cult X, 2018- Cult X, 2019[Paperback]

- The Thief (Deluxe Edition), 2022[Paperback]

The Thief, 2012

The Thief, 2012- The Thief, 2013[Paperback]

The Boy in the Earth, 2017

The Boy in the Earth, 2017- The Boy in the Earth, 2018[Paperback]

The Gun, 2016

The Gun, 2016- The Gun, 2017[Paperback]

The Kingdom, 2016

The Kingdom, 2016- The Kingdom, 2017[Paperback]

Last Winter, We Parted, 2014

Last Winter, We Parted, 2014- Last Winter, We Parted, 2015[Paperback]

Evil and the Mask, 2013

Evil and the Mask, 2013 Bram Stoker Award nominee

Bram Stoker Award nominee- Evil and the Mask, 2014[Paperback]

- Other Editions

Der Revolver (The Gun), 2019German Edition

Der Revolver (The Gun), 2019German Edition Die Maske (Evil and the Mask), 2018German Edition

Die Maske (Evil and the Mask), 2018German Edition Der Dieb (The Thief), 2015German Edition

Der Dieb (The Thief), 2015German Edition- Der Dieb (The Thief), 2017German Edition [Paperback]

- Tokyo noir (The Thief), 2015Italian Edition [Paperback]

- Pickpocket (The Thief), 2013French Edition [Paperback]

L'hiver dernier, je me suis séparé de toi (Last Winter, We Parted), 2017French Edition [Paperback]

L'hiver dernier, je me suis séparé de toi (Last Winter, We Parted), 2017French Edition [Paperback]- Revolver (The Gun), 2015French Edition [Paperback]

- En una noche de melancolía (One Melancholy Night), 2014Spanish Edition [Paperback]

- El ladrón (The Thief), 2013Spanish Edition [Paperback]

- Şeytan ve Maske (Evil and the Mask), 2019Turkish Edition [Paperback]

- Hirsiz (The Thief), 2017Turkish Edition [Paperback]

- Kieszonkowiec (The Thief), 2020Polish Edition [Paperback]

- Dziecko z ziemi (The Boy in the Earth), 2018Polish Edition [Paperback]

- Anata ga kieta yoru ni (The Night You Disappeared), 2019Chinese Edition [Paperback]

- Kyoudan X (Cult X), 2016Taiwanese Edition [Paperback]

- Okoku (The Kingdom), 2013Taiwanese Edition [Paperback]

Aku to kamen no ruuru (Evil and the Mask), 2013Taiwanese Edition

Aku to kamen no ruuru (Evil and the Mask), 2013Taiwanese Edition- Juu (The Gun), 2012Taiwanese Edition [Paperback]

- Suri (The Thief), 2011Taiwanese Edition [Paperback]

Tsuchi no naka no kodomo (The Boy in the Earth), 2006Taiwanese Edition

Tsuchi no naka no kodomo (The Boy in the Earth), 2006Taiwanese Edition- Suri (The Thief), 2015Thai Edition [Paperback]

- Okoku (The Kingdom), 2020Thai Edition [Paperback]

- Tsuchi no naka no kodomo (The Boy in the Earth), 2021Thai Edition [Paperback]

- Kyonen no fuyu, kimi to wakare (Last Winter, We Parted), 2018Thai Edition [Paperback]

- Suri (The Thief), 2017Vietnamese Edition [Paperback]

- Suri (The Thief), 2017Armenian Edition [Paperback]

- Suri (The Thief), 2010Korean Edition [Bunko]

Aku to kamen no ruuru (Evil and the Mask), 2011Korean Edition

Aku to kamen no ruuru (Evil and the Mask), 2011Korean Edition Okoku (The Kingdom), 2013Korean Edition

Okoku (The Kingdom), 2013Korean Edition- Meikyu (The Labyrinth), 2015Korean Edition [Paperback]

Kyoudan X (Cult X), 2017Korean Edition

Kyoudan X (Cult X), 2017Korean Edition- Nani mo ka mo yuutsuna yoru ni (One Melancholy Night), 2009Korean Edition [Bunko]

Prize-winning

Prize-winning Prize nominee

Prize nominee Adapted for Film/TV

Adapted for Film/TV- In Japan there are two major book formats tanko-bon (Tanko) and bunko-bon (Bunko). See Factbook for explanation. The smaller images above are of the Bunko Editions, small-format paperbacks.

- Readers:

If I think about this deeply, it is not that I am writing with someone in mind. I write what I want to write. That is the first principle. Generally, this is based on the issues, questions and topics I am thinking about at any given time.

Once I was asked a question which had nothing to do with my work. I was asked what type of women I like. It was an odd question. A woman posed it and it is probably one of the most unusual questions I have been asked. At that time, I didn’t want to give a physical attribute, so as a joke, I just said someone who wears black stockings. Everyone laughed. I was in South Korea at the time. My reply was a joke, which was luckily very well received.

I don’t read comments but sometimes my editor shares interesting comments with me. None in particular spring to mind, but if someone writes that they read it in ‘one-sitting’ or ‘one-go’, I am happy. I try to write so that the reader will become totally immersed in the story. And if they write that, it means that I have been successful.

- Books:

For international readers I would say that it is The Thief. In Japan I am best known for Cult X. If you look at the figures it is my bestselling title. It has sold more than half a million copies.

However, the truth is that the book I really want people to read most is my latest one. My latest work is always the one I like best. But the one that is probably the easiest to start with is, I think, The Thief.

The Thief is about a pickpocket. It is, I think, an unusual story as not many have been written about pickpockets. It is about life and whether fate is determined or not; and you can enjoy these themes as you read it. And also get a sense of the heightened-anxiety associated with committing a crime, the anxiety of a pickpocket.

Cult X is a much larger work and theme questioning the world we live in. And revolves around cults in Japan. It is about a Japanese Buddhism-based religious sex-cult. A Cult that blends all these aspects together. I think people will find it very interesting.

Five of my books have been made into films. They have all turned out well and I am pleased with all of them. If I am concerned about how they might be adapted or turn out, I wouldn’t give the go ahead.

The five are: Final Life; Fire; Evil and the Mask; Last Winter, We Parted; and The Gun. In the order of their release. And there are others, which are under discussion, that I can’t talk about yet.

I have been writing for 16 years now and am in the good position of being able to have money spent on the covers. It is something that I can now really enjoy. For a number of years I have been in the position to be able to ask for the people I want to work on my covers and I have chosen artists and illustrators, carefully.

For my latest one, Vanishes On the Road Ahead, I asked Hajime Kinoko, an internationally renowned Japanese rope-artist who is also a Kinbakushi (a Japanese bondage rope-master), to create an original image for the book’s cover. I was really pleased I could do this. He has won international prizes and people may have seen or be familiar with his work.

The theme comes first. The theme comes from within me, and the protagonists generally come from part of me. Based on the theme, I try to think about a suitable narrative that matches the theme.

With The Thief many aspects came together. Initially, I was interested in the association between anxiety and the act of committing a crime, and overcoming the fear to commit a criminal act, crossing this line. As I was writing, I thought about the pickpocket’s thieving fingers and how far they’d go before becoming overwhelmed by anxiety. I also thought about the relationship between god and man. It is not god, but man that can actually decide man’s fate. These were the concepts I was interested in, as well as the feeling of being on the margins of society, which is something I have personally felt in the past. It was the combination of these three things that led to that narrative.

How I decide on a title depends on each book. Sometimes it is clear right from the start and I know what the title is and sometimes I can’t decide until I have finished. With Cult X I decided very quickly.

The titles of my works are either short or long. One of these two extremes, never in-between. I think that is the case for my books that have been published in English translation as well.

I decided in my third year at university that I wanted to become a novelist. That is when I started writing. After graduating I spent two years doing part-time jobs. After two years I submitted what I had been working on to a competition (the Shincho Literary Prize for New Writers), which I won about one year later. This was my debut work The Gun.

- Writing:

Yes, what I write is often close to my own experiences and personality. Sometimes what I write is exactly what I have experienced and other times I develop it or re-write it, but often what I write is close to things that have actually happened.

My ideas come suddenly. But they often come while I am writing something. The idea for the next novel often comes to me while I am writing a novel. It is almost like the baton in a relay race. While I am writing I get an idea but decide it is for another novel, and I write the idea down in a different notebook. It is like a relay.

When you start writing novels it becomes an addiction. Once you have written one I don’t think you can stop. It is not that I can’t relax until I have completed something I am working on. It’s more that if I am not writing, I am not calm or settled. I am generally working on two pieces at the same time in parallel.

I am always working on something and it is not the case that once I have completed something I don’t have anything new to work on. I have lots of commissions and requests stacked-up for years ahead. And it has been like this for more than a decade and there hasn’t been a day when I could just think of nothing. It is not good for my health. Even when I am travelling overseas I have to work on serialisations that are in-progress and still running.

A full-length novel takes me about a year to write. But a long work, like Cult X, takes about two and a half years. As for short stories they often take time as well, more than one might expect. It is probably not reflected in the number of pages.

When I write I am ‘canned’ in a hotel. That is where I write. I change hotels to change my mood. I stay in one hotel where I focus on a manuscript I am working on. I then go home. After which I head off to another hotel where I will work on a different manuscript. This is my general approach.

For me the most important thing, the best environment for me, is one where I can avoid noise. I need a quiet place to write. If it is noisy I can’t write.

Also if there is an orange coloured light, for some reason I can relax and write easily. I have an orange light at home but generally a hotel is quieter, which allows me to focus. When I am focused I concentrate so deeply that I have almost no memory of time or the place where I am writing. Without noticing, a few hours can go by and I will have written a significant amount. I then take a break and then start writing again. I write, go for a walk, and then start writing again.

When I am working on a novel I find it best to walk in a noisy crowded place. It can be stimulating and walking in a place like Ikebukuro works well for that. When I get stuck on a section and am not sure how to express what I want to write I think about it and go over it in my head as I walk. But that is not always the case. Sometimes I just walk and think about nothing.

What I write is jun-bungaku, pure literature or literary fiction. But within this genre of jun-bungaku I include aspects of crime fiction and mystery writing.

Sometimes I write immediately using my computer. But often I start writing in a notebook when I am in café. I write my ideas down and then later input them into my computer. That is what happens most often. I then print everything out, and re-read what I have written, annotate it, and then rework the text on the computer. This is a process that I repeat.

No, I haven’t.

I like both.

That is actually something I am working on right now. A spin-off from a film adaptation of one of my books.

But with the film adaption of The Gun, which has just been released, I was commissioned to write one scene specifically for the film. Now thinking back at it, the film is better for having this additional scene. I thought it was necessary for the film and that is why I wrote the dialogue for the scene.

I haven’t experienced writer’s block. There haven’t really been any periods when I didn’t want to write. However, when I am overseas attending an event I try to soak-up the atmosphere and experience where I am and therefore try to avoid writing as far as possible.

- Reading:

I still enjoy reading, of course. I do read for my work, but mostly I read books I want to read. I am currently re-reading Shusaku Endo’s novel Silence. The novel I am working on features ‘hidden-Christians’. I had already read the novel but wanted to read it again. I have also visited Nagasaki to research my latest book.

Dostoevsky. My favourite, is his book, The Brothers Karamazov.

Without thinking about it too much. The Brothers Karamazov is about four brothers. I like all of them. They all had different personalities.

Until I was in high school I hardly ever read any books. However, when I was a high school student my favourite book was No Longer Human (Ningen shikkaku) by Osamu Dazai.

Can I recommend one of my own books? If so, it would be The Thief. It is short so probably good for a book club.

Vice. It is an American news site. English is hard and it is often difficult for me to understand what is being said. I wish they would speak using easier to understand English.

- Japan:

I am not sure why, but in Japan long form fiction sells better than short stories.

I am not sure if anything can be learnt from this or it is a good reference point. But it is a form of encouragement.

Perhaps, it is because Japan is an island nation. And island nations have their own unique cultures.

There are many different individuals. But like in Schindler’s List, there was Sugihara-san. He is someone I respect. In terms of a contemporary figure that is a hard one to answer. It has to be an author, and that would be Kenzaburo Oe.

I don’t think that is the case at all. It is open.

- Interests:

The Fellini film, 8 ½. It is the atmosphere, craft and the world that is captured in the film that attracts me to it.

I was asked to play a cameo role in one of the film adaptations of my books, but I declined. It isn’t something I am interested in or want to do.

That is a hard one to answer. It has to be Shostakovich, classical music.

I don’t go to karaoke. If I am forced to go I don’t sing.

I am not that interested in anime, but I do like manga. Eiichiro Oda, A recent one I like of his is One Piece. It is extremely well put together.

That is a hard one to answer. There isn’t anyone in particular.

My favourite place is Ikebukuro.

I would like to visit countries I haven’t visited before. I would like to see the pyramids.

If I had time off and it was possible I would like to make a watch. Apparently, there are short classes where you can learn to make mechanical watches and clocks. These classes are reportedly popular amongst dentists. Dentists like this kind of precise work and watchmaking is a popular hobby. I would like to have a go at it myself. It is just an aspiration, and I don’t have the time.

Someone I respect is Mother Theresa. She is an amazing figure, but I am sure everyone thinks that and respects her. I can’t imagine anyone disliking her. She only just died so in a sense she is also a contemporary figure.

Dostoevsky or perhaps Camus.

I am member of The Japan P.E.N Club and the Bungeika Kyokai (the Japan Writers Association), which is a jun-bungaku, literary, association.

Baseball.

- Life:

That has to be authors. I learnt from books. There are many different authors that have influenced me.

One day I will give up smoking. Coffee is something I can’t give up. Writing books is also something that I will never be able to give up. Books and coffee!

It must be the moment when I became a professional author. Once it was agreed.

I walk.

My wallet, but I guess everyone has a wallet with them. I always have a ballpen and a paperback book in my bag or with me. I don’t always carry a notebook, but I always have paper, which I use as a type of bookmark in the paperback. I use this for taking notes.

I don’t like using credit cards so I normally carry about 100,000 yen with me. I have to watch out for pickpockets, but that is what I usually carry as it is enough for most situations.

No, there is no link between this and my book The Thief. It is just that I prefer to have this amount and feel more comfortable if I have this amount with me when I go out.

- Awards

2020 – The 73rd Chunichi Bunka Award

2016 – Prix des Deux Magots Bunkamura for My Annihilation (私の消滅/Watashi no shoumetsu)

2014 – David L. Goodis Award

2010 – Kenzaburo Oe Prize for The Thief (掏摸/Suri)

2005 – Akutagawa Prize for The Boy in the Earth (土の中の子/Tsuchi no naka no kodomo)

2004 – Noma Literary Prize for Shade (遮光/Shakou)

2002 – Shinchō Literary Prize for New Writers for The Gun (銃/Juu)

- Testimonials

“One of the most interesting, Japanese crime novelists at work today,” US Today.

“In an era when deep layers of poverty, newly revealed, are raising great social concern, this author understands that fresh perspectives can and must be brought to bear,”Kenzaburō Ōe.

“Nakamura, whose strategically withholding approach to filling in blanks invites conspiracy-minded readers to append whatever paranoid fantasies about government they happen to be dragging about on any given day,”The New York Times.

“Fuminori Nakamura has delivered an edgy Crime Drama/Psychological Thriller filled with enough surprises to keep one guessing. The Pulp-Noir feel, coupled with the psychological extremes visited through the character’s flaws, offers an intense view into the lower depths of the human psyche,“ Reader Comment on Goodreads.com about Last Winter We Parted.

“This is a very good, maybe incredible novel that somehow manages to stay compelling for 350 pages despite the fact that mostly the characters just sit in the dark and hate life,” Reader Comment on Goodreads.com about Evil and the Mask.

- News & Media