Street light with a sculptured cat on an electrical pylon close to the Natsume Soseki Memorial Museum in Tokyo. Photograph: Red Circle Authors Limited.

Street light with a sculptured cat on an electrical pylon close to the Natsume Soseki Memorial Museum in Tokyo. Photograph: Red Circle Authors Limited.Schrodinger’s cat, which changed quantum physics, is probably the best example of the paradigm-shifting breed, but it is certainly not the only one.

Devised in 1935 to mock and critique the scientific wisdom of the time, the Nobel Prize-winning physicist Erwin Schrodinger (1887-1961) dreamt up his fictional feline as a paradoxical thought experiment.

His cat is famously and puzzlingly both alive and dead, until a box is opened, and its narrative structure, designed to point out the ridiculous, involves a radioactive sample, a vial of poison, cats in boxes and a Geiger counter.

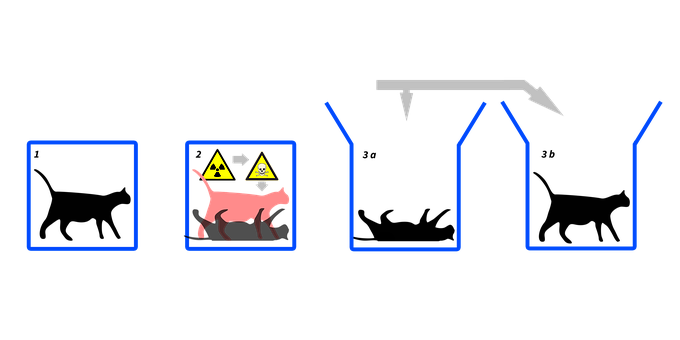

Diagram explaining Schrodinger’s Cat. Source: Wikipedia

Diagram explaining Schrodinger’s Cat. Source: WikipediaThis included the likes of Albert Einstein (1879-1955), Boris Yakovlevich Podolsky (1896-1966) and Nathan Rosen (1909-1995) and the Copenhagen Interpretation, one of the oldest and most important explanations of quantum mechanics, proposed by Niels Bohr (1885-1962) and Werner Heisenberg (1901-1976).

This all took place when quantum mechanics was a new and evolving discipline. A time when many were trying to figure out what this new science actually meant and what its implications were for the modern scientific community.

Schrodinger’s hypothetical cat is an aloof motif still used today to illustrate the strangeness of quantum logic, the act and consequences of close observation and measurement at tiny scales, as well as the confused ambiguity of the observer changing the observed.

-

- The Cynic’s Paw

Soseki’s cat, an alley cat named Chibi, titch or little one, caused a similar paradigm-shifting sensation on publication within the fields of Japanese literature and creative writing.

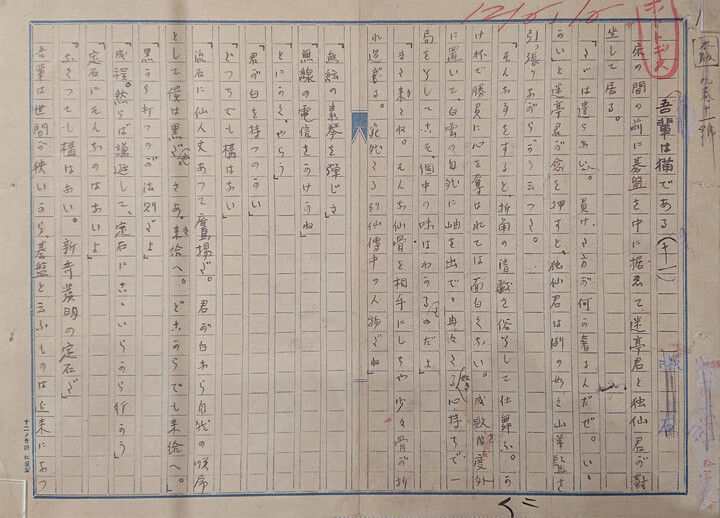

Handwritten manuscript of I am a Cat by Natsume Soseki (1867-1916). Photograph: Red Circle Authors Limited.

Handwritten manuscript of I am a Cat by Natsume Soseki (1867-1916). Photograph: Red Circle Authors Limited.-

- Leaping Eras: Born in Edo Dying in Tokyo

Soseki, the youngest of eight children, was born in Shinjuku in 1867 the last year of Japan’s Edo period (1603-1868), a long and peaceful period (that preceded the Meiji period) during which Japan was shut off from most of the world and Edo, where Shinjuku is located, was Japan’s capital city.

The city Edo, the world’s largest at that time, was renamed Tokyo in 1868 when the Japanese Shogun was overthrown and the Meiji Emperor moved his official residence to the renamed Tokyo.

Like an unwanted kitten from a large litter, Soseki, the future author, was put out for adoption and lived with two different households – only returning to his parental home at the age of nine following the separation of the couple at the second household.

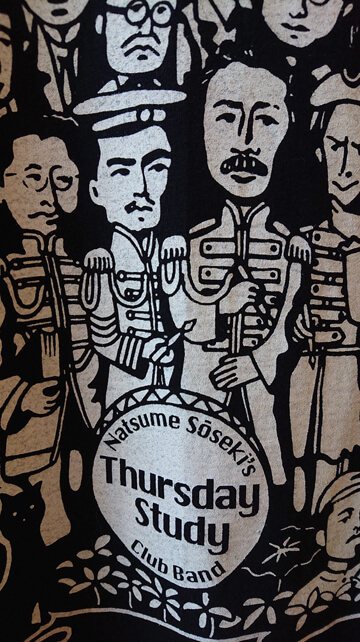

Image depicting the weekly meetings Natsume Soseki held on Thursdays at Soseki-Sanbo, known as the Mokuyokai. Photograph: Red Circle Authors Limited

Image depicting the weekly meetings Natsume Soseki held on Thursdays at Soseki-Sanbo, known as the Mokuyokai. Photograph: Red Circle Authors LimitedAlong the way he picked up the pen name Soseki, which is written using two kanji characters, the Chinese symbols used in written Japanese: gargle and stone, which apparently means stubborn. Soseki’s actual name being Kinnosuke Natsume.

After his return to Tokyo and a series of unwanted and initially rejected visits, a stray cat took up residence in Soseki’s home, becoming his purring muse and inspiring him to write his debut work, a short story written from the perspective of a cat, I Am a Cat, Wagahai wa neko de aru. The published title of the work coming from its first line.

After it was initially read out with the title Nekoden, Cat Story, at a weekly gathering of writers, students and scholars at Soseki’s home it was published in the literary journal Hototogisu, in January 1905 to great acclaim; and due to the huge popular reaction it elicited, triggered more than ten further installments, creating a serial and then a novel.

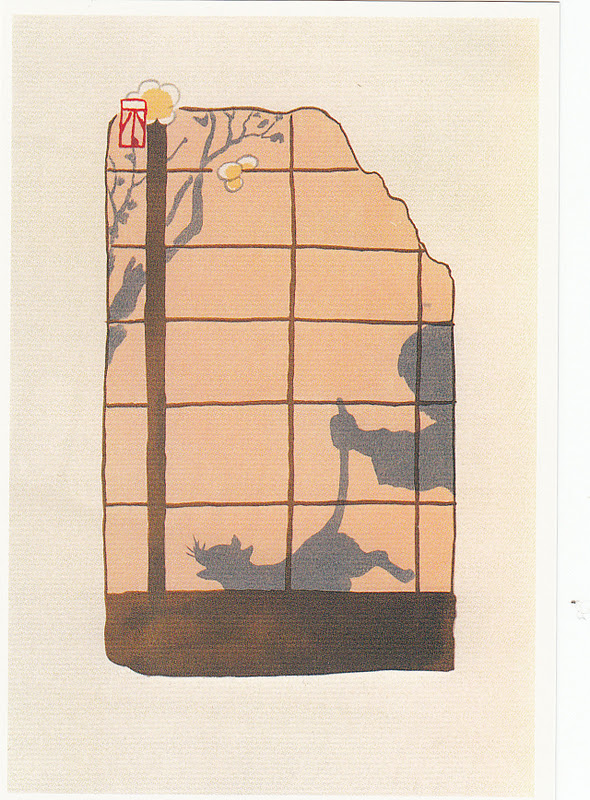

Illustration by the artist Fusetsu Nakamura from Natsume Soseki’s (1866-1943) I am a Cat.

Illustration by the artist Fusetsu Nakamura from Natsume Soseki’s (1866-1943) I am a Cat.The sardonic cat’s caustic observations of its neighbourhood and the household of its ‘master’ Professor Sneeze and his pretentious scholarly associates are fragmented and only tied together by the cat which wanders independently through the life of a Meiji period household and its neighborhood without a formal, traditional or linear storyline.

Poking fun en route at everyone encountered and observed, including Professor Sneeze who no doubt is Soseki’s alter ego, is the order of the day. Soseki through his cat tickles the whiskers of Meiji’s hypocritical elite who often mimicked everything Western, like copycats, sometimes to the point of absurd parody.

“My master’s face is pockmarked. I am told that pockmarks were common enough before…but these days…a face this scarred feels a bit behind the times…How singularly unfortunate for him!”

“… though he is normally to be found asleep in front of it, he does actually spend much of his time with some difficult book propped up before his nose. One must accordingly regard him as a person of at least the scholarly type.”

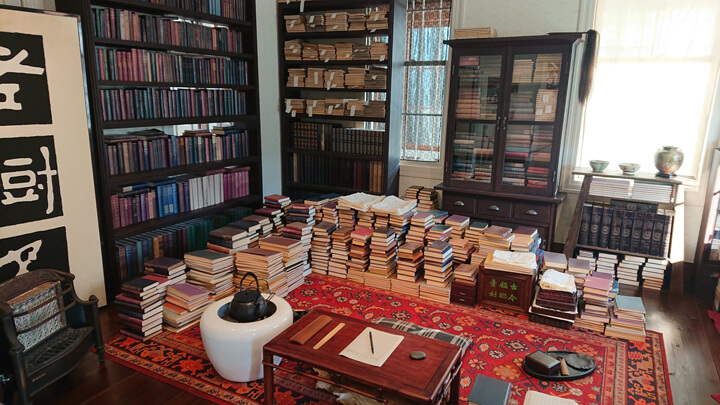

Natsume Soseki’s study at his house in Waseda-Minamicho, now a museum. Soseki spent the last nine years of his life at this property which is know as Soseki-Sanbo. Photograph: Red Circle Authors Limited

Natsume Soseki’s study at his house in Waseda-Minamicho, now a museum. Soseki spent the last nine years of his life at this property which is know as Soseki-Sanbo. Photograph: Red Circle Authors Limited“Though they adopt a nonchalant attitude, keeping themselves aloof from the crowd, segregated like so many snake-gourds swayed lightly by the wind, in reality they, too, are shaken by just the same greed and worldly ambition as their fellow men.”

“The urge to compete and their anxiety to win are revealed flickeringly in their everyday conversations, and only a hair’s breadth separates them from the Philistines who they spend their idle days denouncing.”

After the publication of I Am a Cat Soseki’s writing career took off allowing him eventually to become a full-time author.

Professor Soseki, 1927 by Okamoto Ippei (1886-1948). Hanging scroll, ink and colour on paper at the British Museum showing the author at his writing desk with his cat. Photo: Red Circle Authors Limited

Professor Soseki, 1927 by Okamoto Ippei (1886-1948). Hanging scroll, ink and colour on paper at the British Museum showing the author at his writing desk with his cat. Photo: Red Circle Authors Limited

Still popular today, and seen as a quintessential must-read author for Japanese students, Soseki is known for his skillful fusion of Edo sensibilities and Meiji modernity, a pivotal period that shaped modern-day Japan.

Among such works as Kokoro, Botchan and Sanshiro, which was one of film director Akira Kurosawa’s (1910-1998) favourite books, Soseki wrote 15 novels, which are full of fascinating and idiosyncratic characters with depth, and often a touch of loneliness. Books that still resonate with readers today.

-

- Freethinking and Individualism: Another Modern Paradox?

Sign embedded in the road leading to the Natsume Soseki Memorial Museum. Photograph: Red Circle Authors Limited.

Sign embedded in the road leading to the Natsume Soseki Memorial Museum. Photograph: Red Circle Authors Limited.This said, Soseki avoided or kept a distance from his actual peers. He wrote and spoke about the importance of personal freedom and nurturing individuality, which he considered a moral duty.

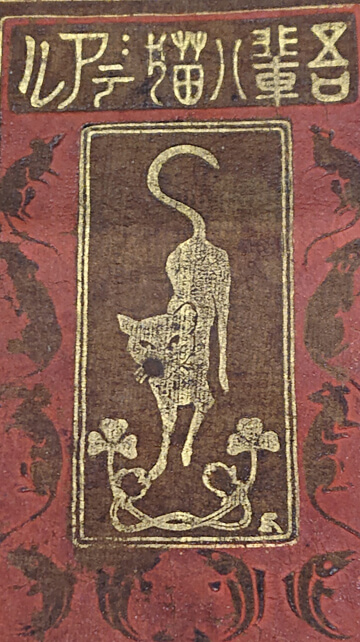

Cover of an early edition of I am a Cat by Natsume Soseki. Photogragh: Red Circle Authors Limited.

Cover of an early edition of I am a Cat by Natsume Soseki. Photogragh: Red Circle Authors Limited.Soseki argued that the stability of the collective was a prerequisite for individualism to flourish. For some these social properties seem correlated and can’t be described or managed independently. Academics today would probably refer to this as the ‘paradox of liberalism’ – the idea that societies can’t prioritise individual liberty above all other political goods without undermining the foundations of individual liberty itself. It was a term coined in the 1970s by the Indian economist and Nobel laureate Amartya Kumar Sen.

After all even an independent cat needs a reliable and peaceful household in which to flourish creating a valuable if slightly odd codependence. Soseki thought that individualism wasn’t about being self-centered or egotistical but about developing one’s own approach while at the same time respecting the personalities of others and fulfilling one’s duties and responsibilities.

A balance that many groups and individuals still struggle to achieve today, in and outside Japan. This somewhat eternal theme of the individual in relation to the collective community is one that Japanese authors including the likes of Kobo Abe (1924-1993) and contemporary authors such as Fuminori Nakamura struggle with and is reflected within their works.

That said, Soseki’s actual cat outlived his fictional cat, which dies in the final installment of the story. The real cat lived with the author in Tokyo and died in 1908 several years before the author’s own death at age 49. So in an odd way, Soseki’s cat, like Schrodinger’s, was alive and dead at the same time depending on whom it was observed by and how.

Grave and memorial for Natsume Soseki’s cats at the back of Soseki-Sanbo which contains the ashes of his cat Chibi and others. Photogragh: Red Circle Authors.

Grave and memorial for Natsume Soseki’s cats at the back of Soseki-Sanbo which contains the ashes of his cat Chibi and others. Photogragh: Red Circle Authors.-

- From Obscurity to Cultural Icon

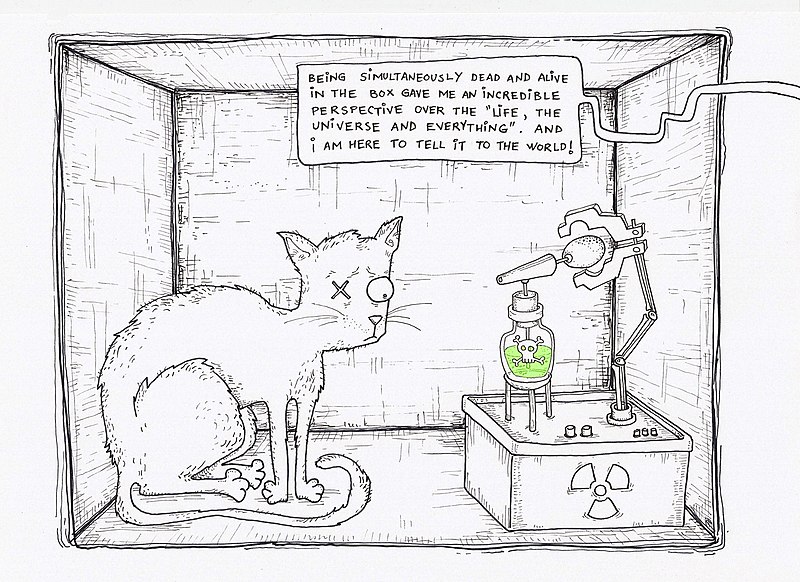

Popular cultural example of Schrödinger’s cat in its box, having its near-death experience. Text reads: ” Being simultaneously dead and alive in the box gave me an incredible perspective over the ‘life, the universe and everything’. And I am here to tell it to the world”. Source: Wikipedia

Popular cultural example of Schrödinger’s cat in its box, having its near-death experience. Text reads: ” Being simultaneously dead and alive in the box gave me an incredible perspective over the ‘life, the universe and everything’. And I am here to tell it to the world”. Source: WikipediaThese two cats conjured up by the furtive imaginations of two trailblazing founders of modern physics and modern Japanese literature, are now cultural icons in the respective worlds of physics and Japanese literature. And both have spawned impressive publishing responses. It is, however, unlikely that either of them knew about each other’s paradigm-shifting cat.

Soseki branded coffee beans on sale at the Natsume Soseki Memorial Museum. Photograph: Red Circle Authors Limited

Soseki branded coffee beans on sale at the Natsume Soseki Memorial Museum. Photograph: Red Circle Authors LimitedAccording to John Nathan’s fascinating biography Soseki: Modern Japan’s Greatest Novelist, Ikeda and Soseki debated some of the big issues of the time including education, religion and science in their London lodgings; something that probably led to Soseki taking a more scientific and objective approach to literature and developing his own special taste: in his case for narrative prose.

Max Planck (1858-1947), another Nobel prizewinner, suggested in 1900 around the time Soseki and Ikeda were both in London that energy was emitted in discreet packets, quanta, and not continuously. The theory later gave birth to quantum mechanics. But this was long before Schrodinger’s cat came on the scene after Soseki’s death, and before cats from Japan or Japan itself gained cultural infamy.

-

- Not a Dead Cat Bounce: A Purr Across Time

For each and every reader or translator there is a different cat that thinks and behaves outside the box of society’s norms, allowing Soseki’s narrative to continue to flourish and delight in the same way as so many quirky cats do on the Internet these days.

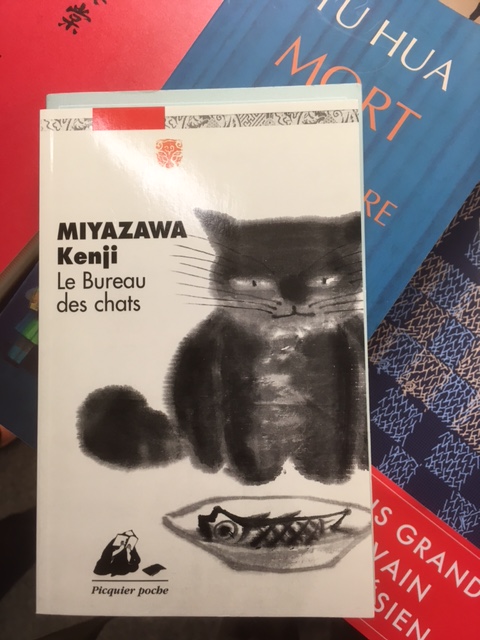

An example of one of the many cat themed works by Japanese authors that are published in translation on sale at a bookshop in Paris. Photograph: Red Circle Authors Limited

An example of one of the many cat themed works by Japanese authors that are published in translation on sale at a bookshop in Paris. Photograph: Red Circle Authors LimitedI Am a Cat has been translated into many languages including English, French, German, Spanish and Chinese, where there are said to be around 20 different versions of this single tale. Cats also feature prominently in some of Haruki Murakami’s novels and Murakami has written about alternative cat worlds such as the Town of Cats included in IQ84, published in 2011.

The British author Nick Bradley‘s 2020 debut novel The Cat and The City, cleverly uses the now familiar plot device of binding a collection of fragmented stories together through a wandering Tokyo cat. It’s another example of the breadth and longevity of the trend, as well as the numerous cats that Soseki has spawned.

Analysis shows that the number of books in Japan with the word cat in their titles has increased steadily, surpassing dog books in 2008, and may now have started to accelerate, increasing this mysterious gap further. There are now so many examples that PhDs on the figure of the cat in Japanese literature and creative writing are being penned.

Neko, the Japanese word for cat, is written with a single kanji character, letter, made up of two underlying component parts, another subtle type of duality in form.

These component parts are known as roots or radicals. Neko‘s roots ‘sub-letter particles’ consist of beast on the left side and seeding on the right creating the special singular kanji character used to write the noun cat in Japanese.

Cats and literature are now a magical well documented and studied combination but does bedtime reading work on feline bookworms, HonNoMushi, too? Photo: Red Circle Authors Limited

Cats and literature are now a magical well documented and studied combination but does bedtime reading work on feline bookworms, HonNoMushi, too? Photo: Red Circle Authors Limited

-

- Different Strokes

Perhaps none of this, including this super position that cats appear to occupy, should really surprise us as cats and humans have been living connected lives for almost 10,000 years since cats were first domesticated. Evidently, cats have historically helped generate many milestones in the canons of many different types of literature.

Beware of the Cat by William Baldwin written in 1561, is yet another good example and many others exist. Despite being written hundreds of years after the first Japanese, and some believe the world’s, first novel, The Tale of Genji, Beware of the Cat is believed by some to be “the first novel published in the English language“.

And this work, sometimes known as Gulielmus Baldwin, also distorts reality, is satirical, and involves the language of cats, as well as the often awkward states that cats can unbeknownst to us and perhaps also sometimes themselves bear witness to. It is also the origin of another narrative dimension, the British construct, that cats are blessed with nine multiple lives.

Japan also has its own pre-Soseki pedigree with a very rich and well documented long history and linage of legendary tales about supernatural cats and storytelling about unusual realms with abnormal states with their own quantum-like distortions.

As well as classical narrative prose and poetry that avoids chronological or progressive timelines. But the arrival of Soseki’s cat, Chibi, in 1905 is considered to have bred a brand new back-alley, perhaps a looping dual carriageway like one, that Japanese writers have leaped into with brilliant creative aplomb.

Within these entangled existences, the latest cognitive behaviour research shows that cats, with their keen powers of observation, olfaction and sonic hearing, and own special timekeeping, are better at decoding human expressions and behaviour than humans are at reading theirs. Perhaps this is what we really need to be watchful of.

No wonder cats eyes, when creatively assumed, can shift tastes and publishing paradigms so successfully. And Japanese ‘Cat-Lit’, seeded by brilliant creative entropy, is for many the crème de la crème.

A set of premium Japanese beers on sale at a Tokyo Department store including Lucky Cat, a brew which "always brings good luck as a partner". A new stimulating creative duality, perhaps. Photograph: Red Circle Authors Limited.

A set of premium Japanese beers on sale at a Tokyo Department store including Lucky Cat, a brew which "always brings good luck as a partner". A new stimulating creative duality, perhaps. Photograph: Red Circle Authors Limited.