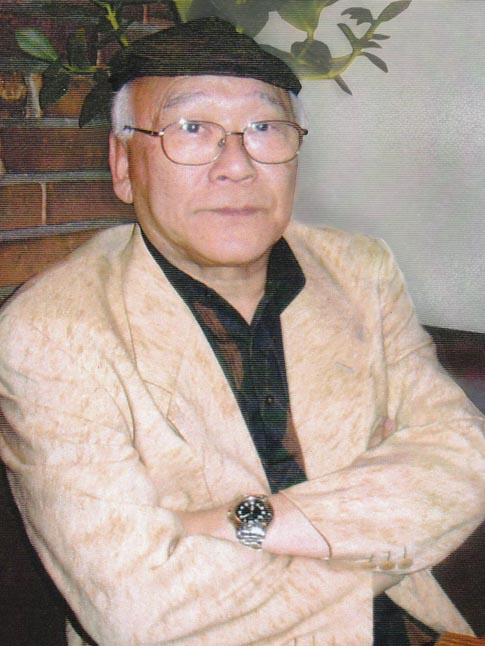

Kanji Hanawa

“I have been writing short stories for as long as I can recall. I am constantly drawn to the theme of extreme situations and the individuals that propagate them: something that is much more common in Japan than most people realize”.Kanji Hanawa is a master of the short story. He has written several hundred since he published his first collection, Garasu no natsu (Glass Summer) to critical acclaim in 1972. In 1962, after graduating from Tokyo University, where he studied French Literature, he spent a few months in Paris, his only stay in the county to whose literature he has dedicated much of his life.

After retiring from academic life (having translated into Japanese 15 novels by some of France’s most eminent authors and studying the works of the French poet Arthur Rimbaud), he dedicated himself to his real passion, writing short stories about life in ancient, modern and contemporary Japan. Two of his novellas have been shortlisted for the prestigious Akutagawa Literary Prize. He passed away in 2020.

“I have admired, the Akutagawa Prize-nominated, Hanawa’s literary style for a long time. Each time he is nominated, I recommend him. And I am delighted that he continues to write at the same prize-winning level,” Shōhei Ooka, novelist.

-

Original, Short and Compelling Reads

Original, Short and Compelling ReadsThe Chronicles of Lord Asunaro

by Kanji Hanawa

A Japanese tale – not about daring ninja or battling samurai – but a hero with a very different penchant. Based on an actual historical figure, the Akutagawa-nominated master short story writer, Kanji Hanawa, takes the reader on a journey of self-discovery, as Lord Asunaro inherits his own Japanese fiefdom and grapples with his role and ultimate legacy. Hanawa provides us with an unusual and entertaining perspective on the psychology of change within Japan when it was still ruled by its men of steel, samurai and shoguns.

- Kanji Hanawa

Kanji Hanawa, born in Tokyo in 1936, was until recently Professor of French Literature at Tokyo’s Kokugakuin University, a highly regarded private liberal arts university, founded in 1882.

He is a respected literary translator, as well as an academic and well-known author, with numerous publications to his name over a long career. He is best known for and prides himself on being a master of the short story format, a genre that has an important and long history in Japan. His first collection of short stories Garasu no natsu (Glass Summer) was published in 1972.

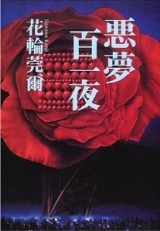

Cover of One Hundred ad One Nightmares, 1996, by Kanji Hanawa.

Cover of One Hundred ad One Nightmares, 1996, by Kanji Hanawa.In addition to his creative writing, Hanawa is an acknowledged expert in 19th century French literature and Authur Rimbaud (1854-1891), the French poet and libertine. While working as an academic he translated 15 French novels into Japanese by authors including Jules Verne (1828-1905), Hector Henri Malot (1830-1907), Paul Nizan (1905-1940), Jean-Paul Sartre (1905-1980) and Frantz Fanon (1925-1961).

His bestselling translated titles were: Jeux interdits (The Forbidden Game), by François Boyer (1920-2003); Vingt mille lieues sous les mers (Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea), by Jules Verne.

Despite his busy academic career, Hanawa has continued to write short stories and novella. He has written and published 14 novella, a few children’s books and collections of short stories. Two examples of his works are Akumu hyaku ichiya (One Hundred and One Nightmares), a staggeringly large collection of short stories published in 2006 and Compos Mentis, published in English in 2008, by Words without Borders.

- Hanawa is focused on short story and novella writing, which occupy a prestigious and important place in Japanese literature

There is a long tradition of short story writing in Japan, and Hanawa represents just one of many prominent and respected exponents of the art. The Nobel Prize-winning author Yasunari Kawabata (1899-1972), for example, was prolific and encouraged others to follow suit.

Are Cats Really Shapeshifters?, by Kanji Hanawa, 2002.

Are Cats Really Shapeshifters?, by Kanji Hanawa, 2002.The tradition began in the Meiji Era (1868-1912), when Japan was liberalizing and opening up to Western influence. New printing technologies were beginning to emerge against a backdrop of social change – triggering the launch of a significant number of literary journals and publications. Shincho (New Tide), for instance, was launched by the respected publisher Shinchosha in 1904. These new magazines and journals created demand from both readers and editors for short stories and serialized novels.

The profitability of these publications is no longer as attractive as it would have been in the Meiji Period, but most major Japanese publishers still publish literary journals today. Japanese authors; new, aspiring and established ones, like Hanawa, also continue to write brilliant short stories and novella that are morphing into new exciting styles and formats that frequently win literary awards in Japan.

Two of Hanawa’s novellas Jumen no matsuri (Tribal Festival) and Furerareta yami (Darkness Touched) were shortlisted for the Akutagawa Prize.

- Kanji Hanawa

Kanji Hanawa and his brother had a difficult childhood as his father, an appeal court Chief Justice, was traditional, strict and had very high expectations for his two sons. He grew up in Tokyo and went to Seijo Gakuen High School, a well-regarded private school, where he was classmates with future international award-winning conductor Seiji Ozawa. After high school he won a place at Tokyo University, Japan’s most prestigious university, where he studied French literature and led an active student life. He graduated in 1960 and went on to study for a PhD, which he received in 1965.

- Japanese Editions

Akumu hyakuichi ya (Hundred and One Nightmares), 2006

Akumu hyakuichi ya (Hundred and One Nightmares), 2006 Jumen no sai (Festival of Scowls), 1971

Jumen no sai (Festival of Scowls), 1971 Akutagawa Prize nominee

Akutagawa Prize nominee Furerareta yami (Touched by Darkness), 1971

Furerareta yami (Touched by Darkness), 1971 Akutagawa Prize nominee

Akutagawa Prize nominee Garasu no natsu (Summer of Glass), 1972

Garasu no natsu (Summer of Glass), 1972 Umoreta toki (Buried Time), 1975

Umoreta toki (Buried Time), 1975 Riki no zukkoke jitensha (Riki's Irregular Bicycle), 1975

Riki no zukkoke jitensha (Riki's Irregular Bicycle), 1975 Sakin wo mitsuketa riki (Riki Who Found the Gold Dust), 1976

Sakin wo mitsuketa riki (Riki Who Found the Gold Dust), 1976 Akumu [meiga] gekijo (I) (Theater of [Famous] Nightmares, Vol.1), 1982

Akumu [meiga] gekijo (I) (Theater of [Famous] Nightmares, Vol.1), 1982 Akumu [meiga] gekijo (II) (Theater of [Famous] Nightmares, Vol.2), 1983

Akumu [meiga] gekijo (II) (Theater of [Famous] Nightmares, Vol.2), 1983 Sakamoto Ryoma to sono jidai (Sakamoto Ryoma and Those TimesBiography of the beloved champion of the Meiji Restoration dubbed the "democratic samurai."), 1987

Sakamoto Ryoma to sono jidai (Sakamoto Ryoma and Those TimesBiography of the beloved champion of the Meiji Restoration dubbed the "democratic samurai."), 1987 Neko kagami (Cat in the Mirror), 1990

Neko kagami (Cat in the Mirror), 1990-

Akumu shogekijo (Small Theater of Nightmares), 1992[Bunko]

- Umi ga nomu (The Swallowing Ocean; vol. 2 of Small Theater of Nightmares), 1992[Bunko]

Neko gaku nyumon (An Introduction to Cats), 1997

Neko gaku nyumon (An Introduction to Cats), 1997 Akumu gojuichi ya (Fifty-one Nightmares), 1998

Akumu gojuichi ya (Fifty-one Nightmares), 1998 Ishiwara Kanji dokuso su (Kanji Ishiwara, the Lone RunnerBiography of the “brains of the army” who, as chief of staff, opposed both the war with China and the war with America.), 2000

Ishiwara Kanji dokuso su (Kanji Ishiwara, the Lone RunnerBiography of the “brains of the army” who, as chief of staff, opposed both the war with China and the war with America.), 2000 Neko wa honto ni bakeru no ka (Are Cats Really Shapeshifters?), 2002

Neko wa honto ni bakeru no ka (Are Cats Really Shapeshifters?), 2002 Umi ga nomu 3.11 higashi nihon daishinsai made no nihon no tsunami no kioku (Swallowed by the Sea: Recollection of Past Tsunami Leading Up To the Great Tohoku Earthquake of 3.11), 2011

Umi ga nomu 3.11 higashi nihon daishinsai made no nihon no tsunami no kioku (Swallowed by the Sea: Recollection of Past Tsunami Leading Up To the Great Tohoku Earthquake of 3.11), 2011 Akumu jyuroku ya: zanmu seiri (Sixteen Nightmares), 2013

Akumu jyuroku ya: zanmu seiri (Sixteen Nightmares), 2013 Yasahisa no yukue (Yasahisa no yukue), 2012

Yasahisa no yukue (Yasahisa no yukue), 2012

- English Editions

- The Chronicles of Lord Asunaro, 2020Red Circle Minis [Paperback]

- Backlight, 2018Red Circle Minis [Paperback] <!--

- Other Editions

- Kaitei niman kairi (Vingt Mille Lieues Sous Les Mers, by Jules Verne), 1968Translation from French [Bunko]

- Kaitei niman kairi (I) (Vingt Mille Lieues Sous Les Mers, by Jules Verne), 2009Translation from French [Bunko]

- Kaitei niman kairi (II) (Vingt Mille Lieues Sous Les Mers, by Jules Verne), 2009Translation from French [Bunko]

Shimoonu·veeyu chosakushuu dai 2. Aru bunmei no kumon kouki hyouronshuu (Simone Weil Collection 2: The Agony of a Civilization - Late Review), 1968Translation from French

Shimoonu·veeyu chosakushuu dai 2. Aru bunmei no kumon kouki hyouronshuu (Simone Weil Collection 2: The Agony of a Civilization - Late Review), 1968Translation from French Arukidashita chisana ki (The Small Tree that Sprung Forth, by Thelma Volkman), 1969Translation from French

Arukidashita chisana ki (The Small Tree that Sprung Forth, by Thelma Volkman), 1969Translation from French Hinin no shisou '68nen 5gatsu no furansu to 8gatsu no cheko (Thoughts of Denial: May 1968, France and August 1968, Czech Republic, by Jean-Paul Sartre), 1969Joint translation from French

Hinin no shisou '68nen 5gatsu no furansu to 8gatsu no cheko (Thoughts of Denial: May 1968, France and August 1968, Czech Republic, by Jean-Paul Sartre), 1969Joint translation from French Furantsu·fanon chosakushuu dai 2. Kakumei no shakaigaku-arujeria kakumei dai 5nen (Frantz Fanon Collection 2: The Sociology of Revolution - 5th Year of the Algeria Revolution), 1969Joint translation from French

Furantsu·fanon chosakushuu dai 2. Kakumei no shakaigaku-arujeria kakumei dai 5nen (Frantz Fanon Collection 2: The Sociology of Revolution - 5th Year of the Algeria Revolution), 1969Joint translation from French Furantsu·fanon: Kakumei no shakaigaku (Frantz Fanon: The Sociology of Revolution), 2009Joint translation from French

Furantsu·fanon: Kakumei no shakaigaku (Frantz Fanon: The Sociology of Revolution), 2009Joint translation from French- Kinjirareta asobi (Les Jeux Interdits by François Boyer), 2009Translation from French [Bunko]

Inbou (Conspiracy, by Paul Nizan), 1971Translation from French

Inbou (Conspiracy, by Paul Nizan), 1971Translation from French Boku no mura (My Village, by Jan Cau), 1971Translation from French

Boku no mura (My Village, by Jan Cau), 1971Translation from French- Antowaanu·burowaie (Antoine Bouillier, by Paul Nizan), 1972Translation from French [Bunko]

- Aden·arabia (Aden Arabia, by Paul Nizan), 1972Translation from French [Bunko]

Shonen tantei buraun 1 (Kid Detective Brown, by Donald J. Sobol), 1973-78Translation from English

Shonen tantei buraun 1 (Kid Detective Brown, by Donald J. Sobol), 1973-78Translation from English Shonen tantei buraun 2 (Kid Detective Brown, by Donald J. Sobol), 1973-78Translation from English

Shonen tantei buraun 2 (Kid Detective Brown, by Donald J. Sobol), 1973-78Translation from English Shonen tantei buraun 3 (Kid Detective Brown, by Donald J. Sobol), 1973-78Translation from English

Shonen tantei buraun 3 (Kid Detective Brown, by Donald J. Sobol), 1973-78Translation from English Shonen tantei buraun 4 (Kid Detective Brown, by Donald J. Sobol), 1973-78Translation from English

Shonen tantei buraun 4 (Kid Detective Brown, by Donald J. Sobol), 1973-78Translation from English Shonen tantei buraun 5 (Kid Detective Brown, by Donald J. Sobol), 1973-78Translation from English

Shonen tantei buraun 5 (Kid Detective Brown, by Donald J. Sobol), 1973-78Translation from English Shonen tantei buraun 6 (Kid Detective Brown, by Donald J. Sobol), 1973-78Translation from English

Shonen tantei buraun 6 (Kid Detective Brown, by Donald J. Sobol), 1973-78Translation from English Shonen tantei buraun 7 (Kid Detective Brown, by Donald J. Sobol), 1973-78Translation from English

Shonen tantei buraun 7 (Kid Detective Brown, by Donald J. Sobol), 1973-78Translation from English Shonen tantei buraun 8 (Kid Detective Brown, by Donald J. Sobol), 1973-78Translation from English

Shonen tantei buraun 8 (Kid Detective Brown, by Donald J. Sobol), 1973-78Translation from English Shonen tantei buraun 9 (Kid Detective Brown, by Donald J. Sobol), 1973-78Translation from English

Shonen tantei buraun 9 (Kid Detective Brown, by Donald J. Sobol), 1973-78Translation from English Shonen tantei buraun 10 (Kid Detective Brown, by Donald J. Sobol), 1973-78Translation from English

Shonen tantei buraun 10 (Kid Detective Brown, by Donald J. Sobol), 1973-78Translation from English- Chibikko buunya (Pipsqueak Bouna, by by François Boyer), 1972Translation from French [Bunko]

Kubinashi uma (The Headless Horse, by Paul Berna), 1977Translation from French

Kubinashi uma (The Headless Horse, by Paul Berna), 1977Translation from French Nagagutsu wo haita neko peroo douwashuu (Cat wearing one tool length, by Charles Perrault), 1978Translation from French

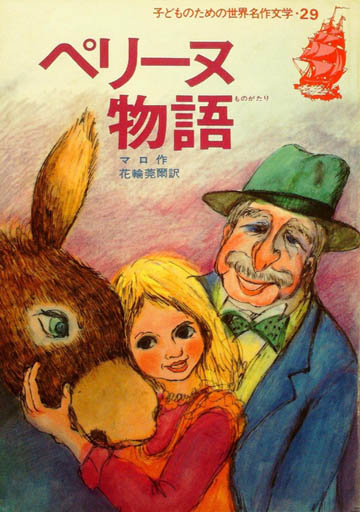

Nagagutsu wo haita neko peroo douwashuu (Cat wearing one tool length, by Charles Perrault), 1978Translation from French Periinu monogatari (Perrine Story, by Hector Malot), 1978Translation from French

Periinu monogatari (Perrine Story, by Hector Malot), 1978Translation from French Ranbo zenzhu (Complete Works of Rimbaud), 1976Joint translation from French

Ranbo zenzhu (Complete Works of Rimbaud), 1976Joint translation from French

Prize-winning

Prize-winning Prize nominee

Prize nominee Adapted for Film/TV

Adapted for Film/TV- In Japan there are two major book formats tanko-bon (Tanko) and bunko-bon (Bunko). See Factbook for explanation. The smaller images above are of the Bunko Editions, small-format paperbacks.

- Readers:

As a general rule, I don’t believe that authors write for a specific reader. However, due to my age I find it more and more difficult to appeal to younger readers. From the perspective of an author, writing for oneself is a sort of contradiction.

Typically, Japanese people aren’t that frank about what’s on their mind. They don’t always say exactly what they are thinking. Only once has a reader said to me: “the ending of your novel was rather strange.” I think that all works of art reveal their essence with their final brush strokes.

Not really. I usually can’t access websites.

- Books:

The majority of my works can be categorized as ‘nightmares’. A simple single jolt has the potential to turn even normal peaceful lives into indescribable nightmares. This is the basic premise of all my work. If I am pushed to choose one that is representative, it will have to be Chirijigoku (Hellbound). It is a piece that reflects my literary style. I would also recommend Anahori (Digging), which was published in the very first issue of a literary magazine called Yaseijidai. This piece also depicts deep fear hidden behind the veneer of normality. Understanding and depicting our hidden fears in a way that connects you directly with these innate deeply hidden feeling is what my reputation is built on. Reading these two stories will help you understand this and at the same time uncover your own deep fears.

Chirijigoku (Hellbound) is very accessible and extremely interesting. The two-volume edition published by Shincho Bunko is a good choice.

A number of years ago Chirijigoku (Hellbound), Shiawase kazoku (Happy Family), and Ginrin no ori (Bicycle Cage) were all adapted for TV by Fuji Television. Unacceptable plots were developed without my approval. No matter how much I pushed for revisions they refused and none were made. They were still broadcasted. It was rather an unpleasant experience.

Do you have any favourite book covers?

The cover of my very first hard-cover was created by Tadami Yamada, an up-and-coming painter at that time. It was a fantastic piece of work. Nothing has surpassed it since.

How do you come up with the titles for your works? Does the title or the narrative come first?

The title and content of a story have a very subtle relationship with each other. It may be different for others, but when a title is decided upon, the contents of the story also materialize. It’s like a lock and its key.

How long did it take for you to get your debut title published?

I had been writing novels since I was an elementary school student. If I assume that was when I was 10 years old, then it would be fair to say that it took 18 years until I got my debut title published.

- Writing:

I wonder what percent of Japanese novelists who write novels based on their own experiences, so-called I-novels, are actually writing about themselves. I have my doubts. My public stance is that I don’t write first-person narratives about myself (I-novels). That is my position. However, if they are just viewed as fiction, who knows what the truth really is.

I think painters have created works based on a given location or from a specific scene, which can become the theme of their work. For a writer, with the exception of where they grew up, there is not a special place. Just because I was born in Tokyo I wouldn’t regard it as ‘my location’.

I’m getting old, and considering old age care, I do not foresee myself being able to write a major work. Seiji Ozawa was my classmate in high school, and Kenzaburo Oe and Shigehiko Hasumi, who recently won the Mishima Yukio Prize, were my classmates at the University of Tokyo. We should all be retiring soon, shouldn’t we?

Much like a painter, I gather up a bunch of rough sketches and look for a connecting thread between them. From that point on it is the hell of deciding if they should in fact be organized around that single thread.

How long does it take you to write a novel or a short story?

It depends of course, but for short stories I like to have a couple of months.

Back when I actually had much more energy for work, I worked on two history books in parallel Sakamoto ryouma to sono jidai (Sakamoto Ryoma and His Era) and Ishiwara kanji dokusousu (Ishiwara Kanji Runs Alone). In addition to them, as readers wanted more, I was also writing a novel.

Do you have a favourite Japanese phrase, idiom or expression?

You mean my personal motto? I have lived up until today with the belief of living without having any mottos. I think it is bizarre to have a motto in your life and being chained by it.

Some people stay up all night writing, but doing so will definitely impact on one’s health in the long run. I stick to writing for between 1 and 2 hours during the day.

Yes. I know there are more convenient ways, but for me I feel that any other approach is ‘dusk in the distance’ as I am an old stick in the mud.

Unlike most, alongside Ryunosuke Akutagawa, I have a rare cutting schizophrenic style. The characteristic of this is clean cut and extremely dry. Pathologically speaking, many of the best European authors, perhaps with the exception of Goethe, and most Japanese authors are on the spectrum of mania, but aren’t schizophrenic.

Never.

Just like Edgar Allan Poe, Akutagawa liked writing short stories, and Franz Kafka’s novels long form works were all failures. Short stories are wonderful.

No. However, my short story collections are used at screenwriter training schools without my permission.

What stops you from being able to write?

Nowdays it would be old age and care.

- Reading:

Of course reading is a part of the trade of being a writer, but I don’t actually read novels. I don’t mean it contemptuously. It is just that there are plenty of other interesting things to do.

Overall I would say it has to be the anarchic style of the French prodigy and poet Arthur Rimbaud. Similarly, Guy de Maupassant and Arthur Conan Doyle amongst others have been influential. I also enjoyed the rakugo (traditional style of Japanese story telling) that was played over the radio after the war. Going back even further, to the Edo Period, there is also Saikaku Ihara, one of the originators and early pioneers of rakugo.

I am fond of Ryoma Sakamoto (1836-1867), who is not fictional, but featured in one of my history books. I also liked the swordsman Toshiro Mifune from the Akira Kurosawa films Yojimbo (The Bodyguard) and Sanjuro. The sword sparring is well-rounded and excellent. The use of pistols is boring, in comparison.

During that time there were no manga and it was impossible to buy books so I could only read from my father’s collection. Such as the works of Soseki Natsume, Leo Tolstoy and others that my father had.

About 50 years ago at a University I taught a class on literary appreciation in which I had the students write papers on books. It was a major problem as nothing decent came out of it. I bet it is even worse now.

- Japan:

Haiku is the world’s shortest form of poetry and is seeing a boom in popularity. I don’t think this tendency towards short stories is limited to modern times.

I happen to know a lot about this from my own personal research and could write a lot about it. Since the publication of Samuel P. Huntington’s The Clash of Civilizations and the Remaking of World Order we have witnessed frequent coordinated acts of terrorism, such as the simultaneous 9/11 attacks, and a religious cultural collision between monotheistic civilizations. As an island nation, Japan has managed to escape the damage caused by monotheism, and retain its own culture. I think this is why.

With the exception of sports that are clearly judged by results and ability, culturally and also in the field of science, Japan isn’t a very free and open environment, at least that’s how I feel. In particular, there has been a decline in journalism and even in television, which is quite deplorable. With a few exceptions, literature is confined to its own shell. I feel that there is no real motivation, nor power to communicate internationally.

One figure who is interesting and I feel close to would be Ryoma Sakamoto (who was a leading figure in the movement to overthrow the Tokugawa Shogunate). But what are you to make of the fact that he was assassinated at such a young age? It was such as waste.

I am not really sure on the actual state of things, but it feels as if people interested in literature and even editors are rapidly disappearing. Reading is difficult and I can only assume that is why everything is being standardized.

- Interests:

I’ve seen most Akira Kurosawa films. However, the recording equipment and technology wasn’t very good in those days, which is a problem. I have also seen all of Steven Spielberg films, starting with Duel. It is remarkable how he depicts nightmare-like situations so beautifully and at the same time the normality of life. In contrast, in most American spy films the agents ignore meal times. Aren’t they ever hungry?

I have little interest.

I love classical music, and I am also rather fond of popular Japanese songs. I even go out to karaoke occasionally.

After reaching a certain age new songs just become difficult to learn. I mainly sing older songs.

I do. I have seen every Studio Ghibli movie, many times. However, recent anime are too noisy. Though if I think back, older anime weren’t really that much different.

That would have to be Toshiro Mifune from Akira Kurosawa films. Dignified actors such as him just aren’t around anymore. The faces of actors today reflect the pampered world we live in. All the truly menacing faces have vanished.

Not particularly. Though I did often go to art museums in the past. Nowdays I don’t really get out that much.

Every day is a day-off for me, and I’ve been pretty tired recently, so I spend most of my time glued to the TV.

Who do you think is the most interesting historical international figure and the most interesting contemporary one?

People say the 20th century was Sigmund Freud’s century, and I too, strongly believe that. No thinker has yet surpassed his outrageous malice.

If you could choose anyone in the world (alive or dead) to discuss writing, creativity and storytelling with, who would you select?

I would definitely choose Edgar Allan Poe. He seems like an unpleasant person to interact with on a personal level. However, his words would certainly be interesting. I’ve been telling stories by fusing Edgar Allan Poe and rakugo, which is probably a rather bizarre thing to do.

I am an advisor for the Tokyo Ryoma Society, which is a Ryoma Sakamoto appreciation group . The chairman is a rather serious doctor, and when he shortened the name to include it on a name plate for the entrance to his house to Toryukai, the police suddenly raided his house as they thought there were a bunch of Yakuza living there, based on the shortened name, which also be rad as The East Dragon Society. One time, we checked every one’s blood type, and to our astonishment, we were all type B. Our chairman, who is a doctor, had a very perplexed look on his face at the time. It is said that Ryoma Sakamoto was also type B. That’s why he was so hyperactive.

I am the type of person who finds it strange how people can make such a fuss out of the Olympics. That being said, I earned a lot through interpretation during the previous Tokyo Olympics.

- Life:

Not really. I have mainly been influenced by those around me rather than by anyone famous.

It’s not so much that giving up living is difficult. It is impossible. People must live out the life they are given.

That would be when I met my wife. She has been an excellent companion. Currently, she is on her sickbed and I must look after her until her time comes.

I’m not sure about overseas, but in Japan it is popular to attribute one’s personality to blood type. I am a type B and thus have little stress, though I am not sure how truthful this is.

Please tell us three good to know facts about you that aren’t widely known?

By saying this I will either be quickly exiled or I will no longer be taken seriously by others but, while I say Freud is great, I actually like Carl Jung more. He expanded unconsciousness as defined by Freud even further. After experiencing many things I have but no choice other than to accept that I am part of this expansion. This is reflected in a number of my works.

Nothing in particular.

Usually some change and about 30,000 yen.

- Testimonials

- News & Media