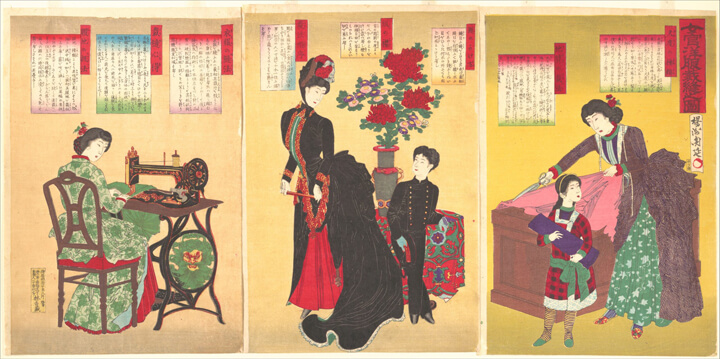

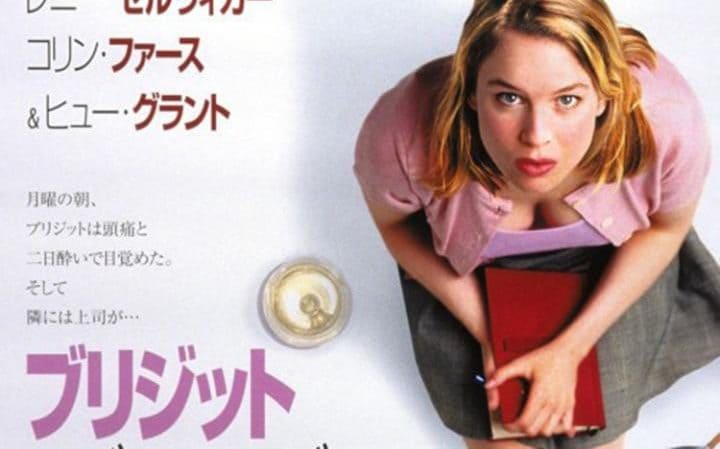

Japanese film poster of Bridge Jones’s Diary. The film series consists of Bridget Jones’s Diary (2001), Bridget Jones: The Edge of Reason (2004) and the third film Bridget Jones’s Baby (2016). Source: Public Domain.

Japanese film poster of Bridge Jones’s Diary. The film series consists of Bridget Jones’s Diary (2001), Bridget Jones: The Edge of Reason (2004) and the third film Bridget Jones’s Baby (2016). Source: Public Domain.T

he amazing success of Bridget Jones’s Diary, by Helen Fielding, published in 1996 in book format is said to have given birth to the genre now known globally as Chick-Lit.  DVD cover of the first series of Sex and The City an American television series about the lives of four female friends in 1990s New York.

DVD cover of the first series of Sex and The City an American television series about the lives of four female friends in 1990s New York.Hundreds of books have been published in the wake of the diary’s success; a successful series of Bridget Jones films has been produced; and dozens of academic papers published including: Bridget Jones, Prince Charming, and Happily Ever Afters: Chick-Lit as an Extension of The Fairy Tale in a Postfeminist Society.

But is this really the first time in literary history that women have written stories from their perspectives and been genre pioneers? As Bridget might write in her diary: “it strikes me as pretty ridiculous: is it any wonder girls have no confidence? This is as old as that Japanese Pillow thing/and Genji…Durr!!”

As Bridget might write in her diary: “it strikes me as pretty ridiculous: is it any wonder girls have no confidence? This is as old as that Japanese Pillow thing/and Genji…Durr!!”

And she would be right. The first golden age of female writers was in ancient Japan: in the Heian Period (794-1185) – a very long time ago.

This was a creative and peaceful period in Japanese history: so much so that its name reflects this. The character Hei means flat and An safety; creating the word “peaceful”.

The imperial court in Kyoto was at its height. Buddhism and the creative arts of the time including poetry, literature, calligraphy, music and art, all flourished. Aristocrats, nobles, and ladies-in-waiting were expected to be literate and capable verse writers. Attraction, appeal and desire came through poetry and beautiful calligraphy – skills that Bridget Jones clearly lacks and never deploys in her pursuit of love and marriage.

Illustration of Murasaki Shikibu writing The Tale of Genji, Genji monogatari, in the 11th Century. The author was a member of the important Fujiwara family but her real name is unknown. The novel tells the story of the life of the ‘Shinning Genji’ and is set in Uji on the outskirts of Kyoto. The first English translation by Arthur Waley was published in six volumes in 1933. Image: japanbarcelona.com.

Illustration of Murasaki Shikibu writing The Tale of Genji, Genji monogatari, in the 11th Century. The author was a member of the important Fujiwara family but her real name is unknown. The novel tells the story of the life of the ‘Shinning Genji’ and is set in Uji on the outskirts of Kyoto. The first English translation by Arthur Waley was published in six volumes in 1933. Image: japanbarcelona.com.Similarly, Bridget Jones’s Diary started as a column in the British newspaper The Independent in 1995, and was published weekly on Wednesdays for three years.

Cover of an Italian edition of The Pillow Book (Note del Guanciale), translated by Lydia Origlia, published in 2002. The first English translation was published in 1889. The original Makura no soshi (The Pillow Book) was completed in 1002.

Cover of an Italian edition of The Pillow Book (Note del Guanciale), translated by Lydia Origlia, published in 2002. The first English translation was published in 1889. The original Makura no soshi (The Pillow Book) was completed in 1002.Some have described Shonagon as one of the world’s first brilliant and notable proto-feminists. Her style of written miscellany and observation is still popular today.

One of the covers of the 13 volume manga adaptation of The Tale of Genji by Waki Yamato. The original novel consists of 54 scrolls or chapters; around a million words; about 430 different characters; 800 poems; as well as 8 or so love interests. It has been translated into many different languages – the English translation is around 1,000 pages long. It spans multiple literary genres romance, travel, diary, poetry, and the supernatural. It has generated numerous publishing spin-offs – one museum in Japan has more than 3,000 different related publications in its collection.

One of the covers of the 13 volume manga adaptation of The Tale of Genji by Waki Yamato. The original novel consists of 54 scrolls or chapters; around a million words; about 430 different characters; 800 poems; as well as 8 or so love interests. It has been translated into many different languages – the English translation is around 1,000 pages long. It spans multiple literary genres romance, travel, diary, poetry, and the supernatural. It has generated numerous publishing spin-offs – one museum in Japan has more than 3,000 different related publications in its collection.R

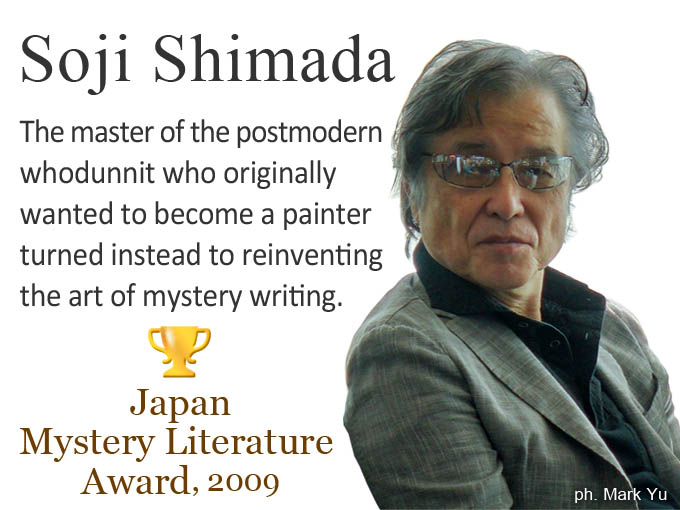

ewriting these stories for contemporary readers recurs every generation as their narratives remain seductive and compelling. The diary format and serialised fiction remain highly popular and are still being exploited by Japan’s best and most creative writers.

Mitsuyo Kakuta, author of the award-winning novel The Eighth Day, about a regular office worker (in love with a married man) who suddenly snaps after an unwanted abortion, is one such author. She is currently adapting The Tale of Genji into modern Japanese for a new generation of readers.

Yoko Ogawa is another example of a contemporary author who has comfortably mastered these genres. Her beautifully crafted novel The Housekeeper and the Professor, which was even reviewed in The American Journal of Mathematics (Volume 57, Number 5) and the international of journal of science Nature, brought her international attention and recognition. However, her short story, Pregnancy Diary, published in the New Yorker, is probably a better contemporary example.

The current cohort of trailblazing Japanese female writers, who are regularly winning Japan’s major literary prizes, also include: Risa Wataya, Randy Taguchi, Miura Shion, and Mieko Kawakami. Despite the challenges, they are rightfully gaining recognition outside Japan in a way that was impossible a thousand years ago for Shikibu and Shonagon.

T

the launch of the film Bridget Jones’s Baby in 2016 more than a decade after the last film Bridget Jones: The Edge of Reason, has provided academics and commentators the perfect opportunity to review the development of Chick-Lit and its international impact. Regional varieties have been spawned across the globe in India, Italy, and Russia as well as many other countries; appealing to young women with their own income, living alone or with friends, with dreams of independence and an exciting urban lifestyle.

When the genre’s popularity in Japan was called into question by The New York Times, one reader wrote to the Editor of the newspaper from Japan in disgust stating that: “Japan is the world capital of chick lit” and “novels by women for women in Japan are no imitation — they are the real thing, a lively and varied genre”.

The latest Bridget Jones film was launched internationally, which created challenges for the subtitle translators. Bridget’s racy coarse language and pet words such as: “fuckwits”, and “bugger” as well as phrases such as: “Actually, last night my married lover appeared wearing suspenders and a darling little Angora crop-top, told me he was gay/a sex addict/a narcotic addict/a commitment phobic and beat me up with a dildo,” are extremely hard to translate and often incomprehensible even to Americans.

The latest Bridget Jones film was launched internationally, which created challenges for the subtitle translators. Bridget’s racy coarse language and pet words such as: “fuckwits”, and “bugger” as well as phrases such as: “Actually, last night my married lover appeared wearing suspenders and a darling little Angora crop-top, told me he was gay/a sex addict/a narcotic addict/a commitment phobic and beat me up with a dildo,” are extremely hard to translate and often incomprehensible even to Americans. Analyzing the genre and how these expressions are interpreted or ignored in different languages and cultures has created a field day for feminist cross-cultural studies. Hiroko Furukawa, for example, has written several papers on the topic deconstructing the “striking gap” between Bridget in the original English and Japanese translation.

The Japanese edition of Bridget Jones’s Diary. Translated by Yoshiko Kamei and published by Sony Magazines in 1998.

The Japanese edition of Bridget Jones’s Diary. Translated by Yoshiko Kamei and published by Sony Magazines in 1998.This is a great pity because if she made the effort, as many readers around the world are starting to do, she would be surprised and delighted by what she’d read in the books, diaries and essays of Japanese writers following in the long wake of the first golden age of women writers of the Heian Period. She might even find the cultural differences titillating; the differences might in fact help her understand herself and her bizarre predicaments better; and she would love the similarities; especially discovering that existential angst is so universal, international and timeless.

© Red Circle Authors Limited

Image from the BBC Radio website used to promote The Pillow Book, by Robert Forrest. A thriller set in the court of the Empress Sadako in 10th-century Japan. First broadcast on BBC Radio 4 in 2008 as part of Woman's Hour Drama. Image: BBC Radio.

Image from the BBC Radio website used to promote The Pillow Book, by Robert Forrest. A thriller set in the court of the Empress Sadako in 10th-century Japan. First broadcast on BBC Radio 4 in 2008 as part of Woman's Hour Drama. Image: BBC Radio.