The Japan Prime Minister, Shinzo Abe, appeared as the character Mario from the Japanese video game at the 2016 Olympics closing ceremony in Brazil promoting the next summer games to be held in Tokyo in 2020. Image: The Indian Express.

The Japan Prime Minister, Shinzo Abe, appeared as the character Mario from the Japanese video game at the 2016 Olympics closing ceremony in Brazil promoting the next summer games to be held in Tokyo in 2020. Image: The Indian Express.J

apanese fairy and folk tales share common themes with their Western equivalents such as hidden or forbidden rooms, strange creatures, epic journeys, supernatural helpers, transformations and attaining treasure and valuable or value-creating tools.

These are same motifs that the video gaming industry, and Japan’s in particular, continues to draw inspiration from and use extensively to depict legends and exciting game play.The gaming fairy tale connection does not only generate fortunes when exploited cleverly, but is a connection that can even impact on legal judgments.

The Supreme Court connected the two in a 2011 judgment about industry regulation in California, concluding that games were a type of modern day Grimm’s Fairy Tales and thus should have the same constitutional protections.

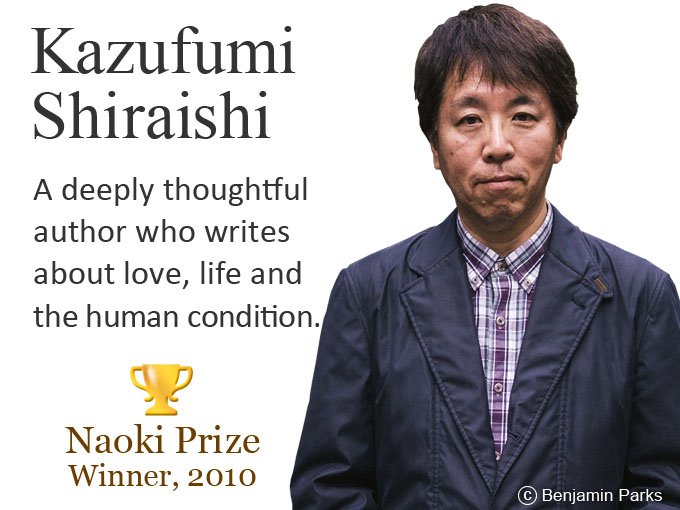

Artwork depicting Super Mario and his Princess. Source: Public Domain.

Artwork depicting Super Mario and his Princess. Source: Public Domain.A common narrative in the West is that after a series of difficult tasks have been successfully completed – mostly by young handsome men – a happy marriage with someone of high status is achieved.

This is subsequently concluded by ‘Living Happily Ever After’.

In contrast, as unfortunately is now increasingly common worldwide, hardly any Japanese folk stories involve happy marriages.

hardly any Japanese folk stories involve happy marriages

Japanese tales often involve sorrow, and women disappearing or returning to animal form with melancholic endings, leaving the reader with a sense of nothingness. They are magical and captivating, but are at the same time harshly realistic.

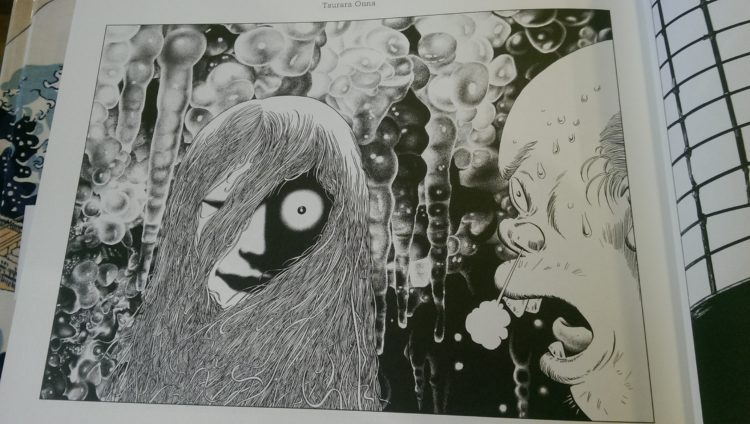

Many famous tales involve non-human creatures turning into women and actively pursuing old or lonely men of poor status who enjoy very happy experiences with these typically beautiful women as a parent or partner for a limited time.

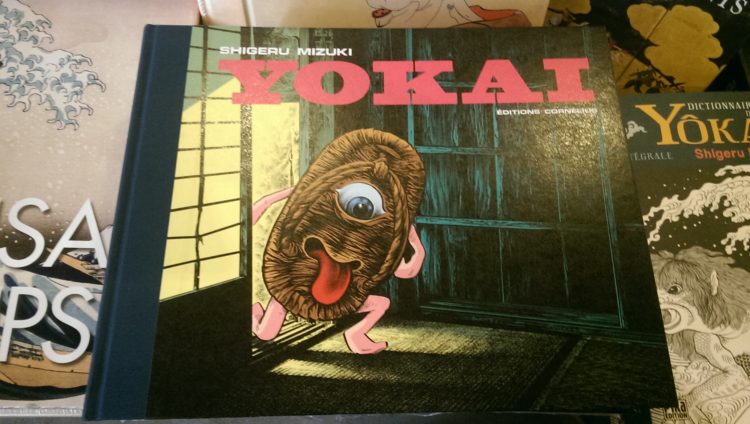

An illustration of Tsurara Onna from a reference book by Shigeru Mizuki on Yokai, monsters from Japanese folk stories. This particular Yokai initially takes the form of a beautiful woman, who is transformed from an icicle, that hopes to marry a lonely single man. Photograph: Red Circle Authors Limited.

An illustration of Tsurara Onna from a reference book by Shigeru Mizuki on Yokai, monsters from Japanese folk stories. This particular Yokai initially takes the form of a beautiful woman, who is transformed from an icicle, that hopes to marry a lonely single man. Photograph: Red Circle Authors Limited.A classic and extremely well-known example of this is Tsuru no Ongaeshi, The Grateful Crane, in which a crane returns a favour to an old childless man who releases her from a trap.

Another example is Tsurara Onna, Icicle Woman, which has many different regional versions.

By contrast, in the West it is often the reverse; marriage with a non-human creature is rare, and sometimes creatures return to human form through magic or the reversal of magic, which can only then lead to a happy eternal union.

A

cademics and experts have conducted all sorts of analyses into these motifs to compare societies, aspirations, culture, gender, literature and psyches. Some academics argue that the Japanese stories were created by women and are about the need in Japan to stress the importance to conform and follow rules for a happy existence;

Japanese stories are about the need to stress the importance to conform, and follow rules for a happy existence;while the Western ones were written by men and are about an individual’s ability to change their status through their own actions creating a new reality for themselves and their future family distinct from their present situation.

Albert Einstein famously said: “ If you want your children to be intelligent, read them fairy tales, and if you want them to be more intelligent read them more fairy tales.”

Unfortunately, we will never know what his view on Japanese fairly tales or video games is, but there is research that appears to indicate that games can help some types of cognitive development if played regularly and not excessively.

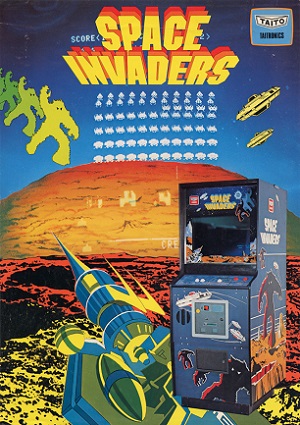

Japan’s video game industry emerged from arcade games in the 1970s. These games were massively popular from the outset. Two Japanese games, Space Invaders and Pacman, helped to develop and transform the industry in Japan and internationally.

A promotional flyer for Space Invaders. Source: Wikipedia.

A promotional flyer for Space Invaders. Source: Wikipedia.A mature ‘amusement industry’ already existed that supplied games for these events and outdoor entertainment areas often on the rooftops of department stores. The confluence of cultural, socioeconomic, as well as industrial and technology, factors created the perfect environment for commercial game winning success.

Street Fighter, launched in 1987, one of the world’s best known games, also started as a Japanese arcade game. New versions of this game have until very recently always been released first as an arcade game before other formats.

Today people still believe the urban legend that the amazing popularity of Space Invaders led to a national shortage of 100-yen coins as so many disappeared into the slots of machines at arcades after the game’s launch in Japan.

One thing, however, that we can probably conclude uncontentiously is that the first wave of internationally highly successful Japanese video games that followed in wake of these arcade games, published in the mid-1980s, opted for familiar and accessible Western fairy tale narratives for their game play.

Games such as Super Mario Bros, which involved navigating the Mushroom Kingdom to find and save Princess Peach or Toadstool, as she is described in the English edition, employed internationally familiar narratives. The same can also probably be said for Sonic The Hedgehog, the multi-million unit selling hit, where players try to steal six Chaos Emeralds.

However, the next wave of games, that came after these, such as Pokemon, which was published slightly later to coincide with the release of the handheld device Game Boy, drew much more heavily on Japanese folk stories for inspiration.

Cover of an illustrated guide to Yokai, traditional Japanese monsters, ghouls, and goblins, by Shigeru Mizuki (1922-2015). Photograph: Red Circle Authors Limited.

Cover of an illustrated guide to Yokai, traditional Japanese monsters, ghouls, and goblins, by Shigeru Mizuki (1922-2015). Photograph: Red Circle Authors Limited.Yokai Watch, named after a class of spirits and phantoms in Japanese folk stories, is also a good example of the highly successful fusion of traditional culture with modern game play.

J

apan’s gaming industry, which has an excellent record of developing blockbusters, is still growing and is forecast to reach a value of 1.5 trillion yen in 2020 with mobile games accounting for 70 percent of the market. The current local market leader is Mixi, the Japanese social network service, with its game Monster Strike, released in 2013, which has a market share of about 12 percent.

The freemium model game draws heavily on traditional arcade games like pinball and is promoted as a mobile arcade-style role play game. Despite its local success the game was not successful internationally and was withdrawn from international markets in 2017.

Image of mobile phone game Monster Strike.

Image of mobile phone game Monster Strike.Japanese folktales have captivated and inspired Japan’s most creative individuals for generations. The influence of these ancient tales of old can be found in manga, anime, science fiction and even in Japan’s international space programme.

A Japanese VLBI spacecraft, The Kaguya Lunar Obiter, named after Princess Kaguya, a story also known as The Tale of the Bamboo Cutter, circumnavigated the Moon between 2007-2009 taking photos of the Moon in Ultra-High Definition.

Gaming is embedded in modern Japanese culture and the nation’s zeitgeist. Even Japan’s politicians are now proud of its gamers and are trying to adopt their global appeal to promote Japanese soft power.

A

cademics study the topic, and references to gaming also appear in novels by some of Japan’s most highly regarded contemporary authors, including Haruki Murakami, who wrote in his 1988 novel Dance Dance Dance about an ‘unnamed’ writer: “My peak? Would I even have one? I hardly had had anything you could call a life. A few ripples some rises and falls. But that’s it. Almost nothing. Nothing born of nothing. I’d loved and been loved, but I had nothing to show. It is a singularly plain, featureless landscape.

I felt like I was in a video game. A surrogate Pacman, crunching blindly through a labyrinth of dotted lines.I felt like I was in a video game. A surrogate Pacman, crunching blindly through a labyrinth of dotted lines. The only certainty was my death.”

His novels and the so-called genre of fiction he has pioneered, ‘magical realism’, sometimes involve transformations, hidden spaces, quests, and individuals searching. These links have now come full circle as his writing is being exploited in an online fund raising campaign to finance a video game called Memoranda.

According to the fund raising campaign (which at pixel time had raised US$25,000) the inspiration for the game came from his short stories. The game aims to utilize odd characters, “Murakami’s magic” and “strange circumstances” to create surreal compelling game play, based on his magical realism.

The rich and varied narrative tradition of mukashibanashi, folk tales, no doubt will continue to inspire Japan’s creatives, be they game designers or authors, no matter how the psychoanalysts interpret their work, the creatives themselves or Japan’s wonderful legacy of ancient stories. They are retold generation after generation in new bold and exciting variants and formats that are destined to continue to entertain the world. Proving that even after the game is over, like life itself, the narrative continues.

© Red Circle Authors Limited

Space Invaders was created by Tomohiro Nishikado and released in 1978. There were 100,000 units installed across Japan in its launch year. It was originally manufactured and sold by Taito Corporation in Japan, who sold 300,000 units in Japan alone.

Space Invaders was created by Tomohiro Nishikado and released in 1978. There were 100,000 units installed across Japan in its launch year. It was originally manufactured and sold by Taito Corporation in Japan, who sold 300,000 units in Japan alone.