Traditional Japanese dolls for sale at Narita Airport Japan. Photograph: Red Circle Authors Limited.

Traditional Japanese dolls for sale at Narita Airport Japan. Photograph: Red Circle Authors Limited.I

mages of human-like dolls or doll-like humans are widely associated with Japan. The most famous of all must be the Geisha, which has captivated people for centuries in all its forms: human, doll, literary, animated, drawn, painted and computer generated.Dolls and their modern equivalents: figurines or figures, are everywhere in Japan. Reporters and television journalists love covering the latest models, evolutions and uses when they write about either the sophisticated, the geeky or dark sides of modern Japan.

Dolls go back to ancient times in almost all cultures and not unexpectedly feature in many different genres of Japanese literature, especially ghost and horror stories.

Dolls from the Heian Period (794-1185) were used to protect, bring good health and happiness, and purify at all stages of human life: from creation to birth, and onwards. Sometimes they would be displayed and at other times given as offerings at shrines.

Children enjoying the Hinamatsuri or Dolls Festival in Japan. The Festival traces its origins back a thousands years to the Heian Period. The dolls represent the Emperor and Empress displayed in traditional court dress. Image: Public Domain.

Children enjoying the Hinamatsuri or Dolls Festival in Japan. The Festival traces its origins back a thousands years to the Heian Period. The dolls represent the Emperor and Empress displayed in traditional court dress. Image: Public Domain.The festival today is about the collection, admiration and display of dolls often on platforms covered in red cloth. The festival is associated with and linked to Japan’s first novel – according to some, the world’s first novel – The Tale of Genji, written over a thousand years ago.

Japanese Doll, bakery insert card from the Pinocchio Circus Performers series (1930–1939), designed by Walt Disney Productions. Credit: The Jefferson R. Burdick Collection at The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

Japanese Doll, bakery insert card from the Pinocchio Circus Performers series (1930–1939), designed by Walt Disney Productions. Credit: The Jefferson R. Burdick Collection at The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.Bunraku, founded in Osaka in 1684, a traditional form of puppet theatre that historically competed with Kabuki is one famous example; Hello Kitty is probably the ultimate doll representative of Kawaii-culture. Anime and manga have their own doll cultures of Cosplay and Figures; Smart Dolls and Emoji are available for the technology obsessed; the hobbyist movement make their own; the craft movement have origami dolls; and lonely men have, the often reported, synthetic life-sized dolls.

Doll motifs and narratives started appearing in the works of many leading Japanese writers in the Meiji Era (1868-1912) at the time of Japan’s rapid modernization. For many this was a period of economic and cultural shock.

A similar revolution in fiction writing was also taking place and the number of novels in translation available in Japan increased rapidly.

The invention of new expressions and words were sometimes required to translate these books. Not just new scientific, technical and medical terms, but also new words and expressions to reflect concepts such as the Western ideal of ‘romantic love’ and the Western concept of novel in Japanese.

As the country was encouraged to embrace all things Western in its race to catch up and take its place as an ‘equal amongst the leading Western powers’ societal rules changed, homosexual male sex was banned for the first time in 1872 (for a period of 8 years), for example, and relationships between men and women, as well as expectations, changed.

Academics think that it was during this period, which some argue caused sexual repression, that Japanese men first started to focus their attention on inanimate objects that reminded them of tradition, quiet contemplation and innocence.

Subsequently, ‘Doll-love’ novels started to appear that featured dolls and also the aesthetic of ‘human-dolls’- far removed from the dolly-birds of London’s swinging ’60s.

The first such novel is said to be the short story Love of a Brute, by Rampo Edogawa (1894-1965), which includes a sex scene with a doll. The highly influential Edogawa pioneered modern mystery writing in Japan and a prize named after him has been awarded to mystery writers since 1955; several of his works feature doll-like people and human-like dolls.

Junichiro Tanazaki’s novel Some Prefer Nettles (1929) where the protagonist Kaname falls in love with a Bunraku puppet from the Edo period after his marriage starts falling apart, is another important example.

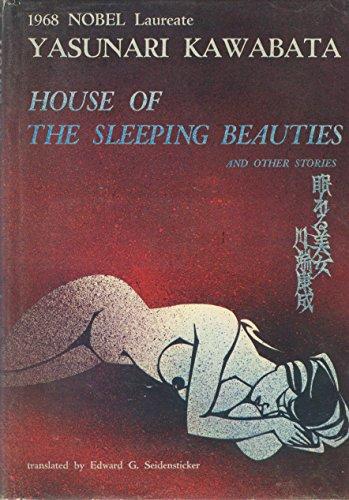

The Nobel prize winner, Yasunari Kawabata’s novella House of the Sleeping Beauties, published in 1961, featuring drugged young women who become doll-like partners that old men can sleep next to, is yet another often cited example.

According to Mariko Kaga, an actress famous for playing fame fetale characters in Japanese films, when she was about 15 in the late 1950s she often met Kawabata, generally for breakfast but he also came to plays she performed.

Cover of English translation collection of short stories by Yasunari Kawabata including the novella House of the Sleeping Beauties, Nemureru Bijo, originally published in 1961 in Japanese.

Cover of English translation collection of short stories by Yasunari Kawabata including the novella House of the Sleeping Beauties, Nemureru Bijo, originally published in 1961 in Japanese.Like, the visitors to the house in Kawabata’s novella there was no “physical component” to their relationship. But the relationship did develop with Kaga staring in the 1965 film adaptation of Kawabata’s novel With Beauty and Sadness, which was originally published in 1964, Japan’s Olympic year.

Kawabata’s novella has been influential in and outside Japan. It is credited with being one of the inspirations behind the 2011 Australian film Sleeping Beauty, written and directed by Julia Leigh.

The “erotic film” won critical acclaim and was shown at many different film festivals including Cannes and Stockholm where the Kawabata connection was discussed. A key plot device in the film is a sedated young women, like Kawabata’s novel. The film also features a Go player in an apparent reference to the author.

In one of the contemporary writer Ira Ishida‘s brilliant short stories, depicting marginalized youth, in his collection Ikebukuro West Gate Park (1997), which has been made into a television series, there is a story of an anesthetist that drugs young girls to the point of death in prearranged transactions with them. So, as you can see, this narrative of the compelling attractive aesthetic of lifeless doll-like women is still very much alive and well in Japan.

B

izarrely and somewhat disturbingly, the cult extends beyond the printed page and into the real world. There is a trend among young Japanese girls to look like Living Dolls. It’s a phenomenon widely reported by the likes of The New York Times. Articles have highlighted the staggering amounts some young girls are willing to invest to look like a traditional French porcelain doll or a Barbie. Other pieces have drawn the reader’s attention to the ways in which visitors to the famous doll museum in Yokohama are dressed.

Digital media and celebrity culture is making people much more image conscious than in the past while allowing niche groups of people with obscure and unusual shared interests to connect. Nevertheless, there is still a major drive to be seen as authentic in many countries. In contrast, some people in Japan are striving to look as synthetically artificial and doll-like as possible.

Doll-making, and doll-culture like literature changes and evolves. Modern ball-jointed dolls (BJD) were pioneered in Germany in the 1930s by the German artist and surrealist photographer, Hanns Bellmer; spawning a new development lineage leading to the BJD hobbyist movement in Japan, which tens of thousands of people are now part of; and Asian ball-jointed dolls (ABJD). These dolls have been influenced significantly by traditional Japanese dolls.

Japanese Smart Dolls are a new type of Japanese doll promoted by Danny Choo, the Tokyo-based son of the famous shoe designer Jimmy Choo. Image from Danny Choo’s website: Culture Japan.

Japanese Smart Dolls are a new type of Japanese doll promoted by Danny Choo, the Tokyo-based son of the famous shoe designer Jimmy Choo. Image from Danny Choo’s website: Culture Japan.The Super Dollfie (SD), is an example of a particularly sought after brand, which even has a secondary market for dolls that have been customized and clothed.

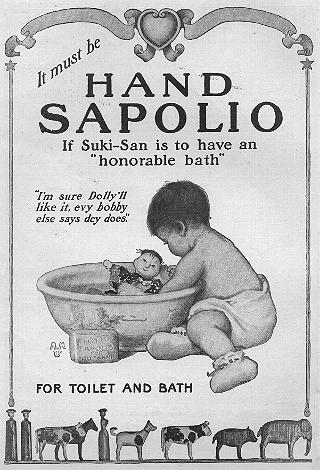

Hand Sapolio Soap Advertisement (1908), United States. Source: Judy Shoaf, University of Florida.

Hand Sapolio Soap Advertisement (1908), United States. Source: Judy Shoaf, University of Florida. Otona-driod (adult female robot) at the Miraikan (National Museum of Emerging Science and Innovation) in Odaiba, Tokyo, Japan. Photograph: Red Circle Authors Limited.

Otona-driod (adult female robot) at the Miraikan (National Museum of Emerging Science and Innovation) in Odaiba, Tokyo, Japan. Photograph: Red Circle Authors Limited.Doll metaphors have been commonly used to describe Japan since the 19th and 20th centuries, a period when Japanese dolls were already very popular in Europe and America.

Unflatteringly, perplexed Western commentators can still on occasion compare some of the female televisions announcers and personalities on Japanese television to mascots; elevator girls in stores and hotels to dolls; and female staff working at Japanese departments stores, who line up wearing white gloves and bow gracefully when the doors to their stores are opened each morning, to humanoids. There is a long history and pedigree of these types of comments and observations.

Before the Second World War Japanese dolls were often referred to as ‘Jappy,’ ‘Jappie,’ the ‘Jap doll,’ or ‘a little Jap’ and children’s books, songs and advertisements often used similar language or stereotypes of Japanese people being doll-like, sleeping on the floor, and frequently bathing.

T

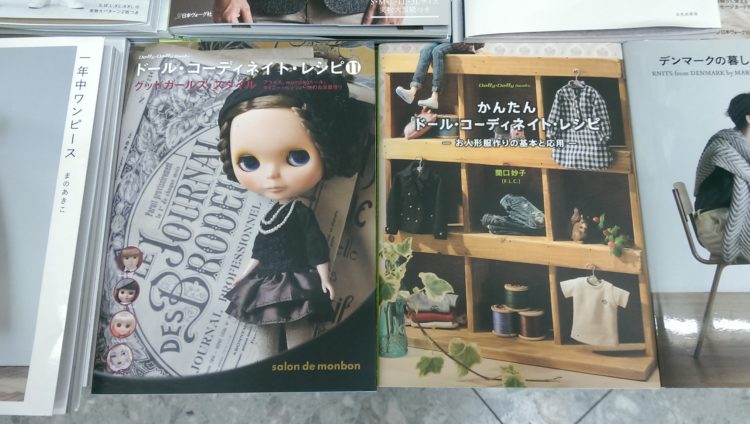

he definition of a doll differs from country-to-country and person-to-person. The Japanese word for doll, Ningyo, is made up of two characters: ‘person/human’ and ‘form/shape’.  Magazines are published in Japan catering for its various doll fans and collectors. Cover images of doll magazines on sale in a Japanese bookstore. Source: Red Circle Authors Limited.

Magazines are published in Japan catering for its various doll fans and collectors. Cover images of doll magazines on sale in a Japanese bookstore. Source: Red Circle Authors Limited.Perhaps, this is the very essence of their popularity in that you can project whatever you want onto them; you can admire them; display them; play with them; mimic them; or study them for an academic thesis.

Modern and contemporary authors like their predecessors from the Meiji Era are finding them a rich backdrop and an easy to exploit motif for creative writing. Unsurprisingly, they also have their own views, make their own interpretations, and develop their own narratives.

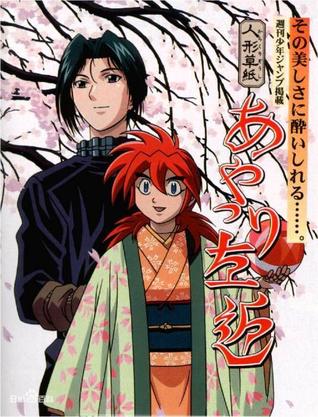

Cover of Doll Puppeteer Sakon (Karakurizoshi Ayatsuri Sakon), written by Masaru Miyazaki and illustrated by Takeshi Obata. The manga follows Tachibana Sakon, a Bunraku puppeteer who solves mysteries with Ukon, a puppet. Originally published 1995-6. Image: Wikipedia.

Cover of Doll Puppeteer Sakon (Karakurizoshi Ayatsuri Sakon), written by Masaru Miyazaki and illustrated by Takeshi Obata. The manga follows Tachibana Sakon, a Bunraku puppeteer who solves mysteries with Ukon, a puppet. Originally published 1995-6. Image: Wikipedia.Other examples include: The Temple of Wild Geese and Bamboo Dolls of Echizen by Tsutomu Minakami (1919-2004); and Kanji Hanawa’s short story Dress-up Crying Doll.

Takako Takahashi’s (1932-2013) novella about a woman who enjoys the pleasure of her young male doll every night, Love of a Doll; and Vacation of Boy Mikazuki, by Mayumi Nagano, are two examples of novels featuring dolls written by women.

T

raditionally in Japan, inanimate, man-made objects including dolls and needles are thought to have a form of spirituality – even souls. This, surprisingly, gives rise to ‘funerals’, kanshasai, last-right appreciation ceremonies for dolls; and Hari Kuyo for broken needles, which are conducted at temples and shrines.

Hari Kuyo at Horin-ji Temple, Kyoto. Photograph: Sharing Kyoto.

Hari Kuyo at Horin-ji Temple, Kyoto. Photograph: Sharing Kyoto.Dolls are brought, prayers made, and financial offerings of around 3,000 yen given, before the dolls are discarded. The number of dolls being brought to the Meiji Shrine in Tokyo, located near Harajuku, which is famous for youth fashion and culture, increases every year.

The spiritual boundaries between people and treasured and favoured objects is not as clear-cut in Japan as in the West. People sometimes connect at a deep level with inanimate human-shapes (Ningyo) be it a traditional doll, robot or Bunraku puppet.

Some observers go as far as stating that the array of dolls and statues in Japan is a form of cult-like pagan idolatry, and that Japan today is how most societies might still be if Judeo-Christian values hadn’t gained momentum.

Without over analyzing things, and spoiling the fun, we can safely conclude at least two important things: 1) dolls are an integral part of Japanese culture and will remain so; and 2) fortunately, Japanese authors will continue to write unusual, compelling and highly readable books about them for many years to come.

© Red Circle Authors Limited

Image of famous haunted Hokkaido doll, Okiku, originally purchased in 1918, whose hair continues to grow. Photograph: The Occult Museum.

Image of famous haunted Hokkaido doll, Okiku, originally purchased in 1918, whose hair continues to grow. Photograph: The Occult Museum.